Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements and Dedication

A project of this size is never a one-person job and I would like to thank Ken Ritchie, Amy Rodger and Martin Steven in particular for their constant help, guidance and support. Alasdair Stuart contributed magnificently to the sections on the results council-by-council and equalities. Other colleagues have assisted with the text and gathering data, including Christine McCartney, Gertrud Malmersjo and Hywel Nelson. I would also like to thank members of the ERS who contributed thoughts, including our Chair, Colin Rosenstiel. Errors and omissions are my own responsibility, and although the report is broadly in line with ERS policy, interpretations and expressions of opinion are also my own.

Thank you also to the officers who work in the elections and information departments of Scotland’s local authorities who have provided data, and to several councillors of various parties who have contributed their insights.

Particular credit is due to the Fairshare campaign, notably James Gilmour, Andrew Burns, Rob Munn, Ian Baxter, Willie Sullivan, Ken (again), Amy (again) and Ross Martin, not only for their help in writing the report but for making it all possible in the first place. I would like to dedicate this report collectively to Fairshare’s campaigners.

Lewis Baston

Director of Research Electoral Reform Society November 2007

Introduction

Introduction

The Scottish local elections on 3 May 2007 were the first major use of the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system in a public election in Great Britain. The introduction of STV followed decades of campaigning by electoral reformers and, particularly after the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, was the subject of many consultations and often heated debates among Scotland’s politicians and parties. While the eventual decision to use STV for council elections might have appeared as a pragmatic deal between coalition partners in the Scottish Parliament, pro-STV campaigners always argued that STV was needed to give Scotland a better democracy with more representative institutions.

STV was not entirely new. Scotland had used it to elect its Education Boards in the 1920s, but these boards did not have the range of powers of modern local authorities, and although ‘university’ seats at Westminster were elected by STV in the first half of the last century, there were only 12 of them. The Republic of Ireland has used STV for all of its elections and the system has been re-introduced to Northern Ireland for all elections except those for Westminster, but the different political contexts in Ireland, both north and south, meant that the use of STV would be a very different proposition when transferred to mainland Britain.

These elections were therefore of much greater significance than the normal four-yearly battle for council seats. Politically, they have resulted in a dramatic redistribution of power between the parties in Scottish local government. They have ended the undeserved majorities that have given some party groups control with little effective opposition, rescued others from undeserved impotence and, in most local authorities, they have required parties to come together to form administrations. Most votes did something to get someone elected, and most voters now have councillor of their choice. In terms of election administration, these elections saw a number of innovations, both in voter education campaigns and in vote-counting technology.

But the most significant aspect of the elections is what they may mean for the future. Many regard STV – a proportional system which at the same time allows voters to choose and rank candidates – as being the connoisseur’s choice of electoral system and wish to see it used in all UK elections. It has already been recommended for Welsh local government by the Sunderland Commission, while the Arbuthnott and Richard Commissions have raised it as a possibility for the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly. But, in spite of STV’s apparent growing popularity, the system nevertheless has its opponents: there are those who have argued, for example, that it is too complicated, that it will dilute the nature of local representation, that it will reduce the decision-taking effectiveness of local councils. To what extent do the Scottish local election results support the claims made by proponents of STV, and to what extent do they justify the concerns of its critics? The answers to these questions may influence the direction and pace of electoral reform in the UK and it is therefore such questions that we address in this report.

STV is a more sophisticated system than FirstPast-The-Post (FPTP). Analysis of the results therefore allows a more sophisticated approach that can provide us with a fuller picture of how voters view the parties. As these were the first STV elections, however, as well as looking at party fortunes we have also examined the extent to which voters were able to use the system effectively, and in looking at the results we have needed to disentangle changesresulting from the change in system from those arising from swings in party support.

Our analysis is extensive, but our conclusions are clear:

- STV has produced much more representative councils than would have been elected under the former First-Past-The-Post system;

- parties appear to have adapted well to the new system, although we expect that parties will develop their techniques as they gain experience of STV campaigning;

- voter understanding of the system appears to have been generally good, with a relatively low level of spoilt ballot papers (unlike the Scottish Parliament election held on the same day);

- most votes mattered, in the sense that they contributed to the election of a councillor.

Summary

Part1: What happened in the elections?

The report begins by looking at the outcomes of Scotland’s local elections in May 2007 and considers the effect of the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system, used for the first time in those elections.

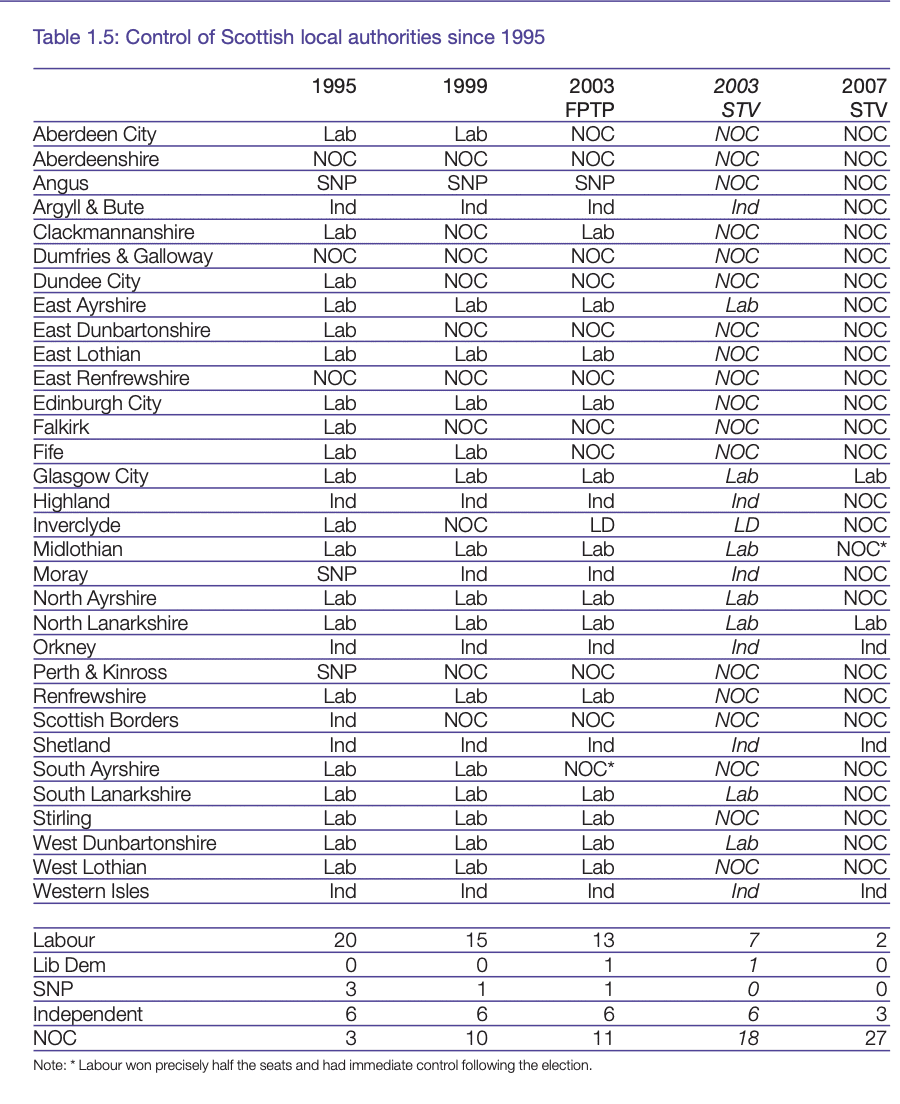

The first chapter discusses the results. With the change to a new, proportional voting system, significant changes in the pattern of representation across Scotland’s councils might have been expected, and this was indeed what we saw. Prior to the elections, Labour was the strongest party in Scottish local government but its position was far from dominant – it only controlled 13 of the 32 councils and there were almost as many councils in which no single party or group had overall control. In 2007, Labour was the only party to win outright control of any councils, winning Glasgow and North Lanarkshire, while Independents control three further councils. However, the norm (27 out of 32 councils) is now no overall control (NOC) and a varied pattern of coalitions has emerged.

However, in looking at the changed fortunes of the parties, it is important to separate out two effects – that of the change in voting system and shifts in party support. We have done this by looking at what the 2003 elections might have produced if STV had been used then. This shows that while there was a marked swing in support from Labour to the Scottish National Party (SNP) in the May elections, the introduction of STV also had a pronounced effect, with parties losing seats which they had held through the distortions of the First-PastThe-Post (FPTP) system and also gaining seats that the unfairness of FPTP had denied them.

Councils across Scotland are now much more representative of the views of their voters. No longer are there councils where parties have majorities that cannot be justified by electoral support; where parties with significant support have no, or few, seats; or where the largest parties in terms of seats are not those with most votes. Measures of disproportionality show a marked improvement over the pre2007 situation. If the elections had a clear winner, it was the voters who got what they wanted.

Chapter 2 examines the results from the perspectives of the political parties. The Conservatives used the opportunity presented by the new system to put up nearly a full slate of candidates in mainland Scotland, including candidates in many areas where the Conservatives had not previously contested elections. Their chances would have been greater had their national popularity stood a bit higher, and if they had managed to obtain more transferred votes from supporters of other candidates. Labour had a bad election, but it was not without its brighter spots, including full control of two councils and more council leaders than any other party. The bulk of Labour voters tended to transfer preferences to other Labour candidates, meaning that fears of split votes turned out to have little justification. If Labour’s vote recovers from its low point in 2007, the party could win back a significant number of councils.

The Liberal Democrats, having campaigned for STV in local elections, had a disappointing overall result, with gains in some areas such as Highland being matched by defeats in previous strongholds like Inverclyde. They were relatively successful at attracting transfers from other parties, but this leaves them vulnerable to any future loss of support.

The SNP had a successful election in local government as well as Holyrood, becoming – narrowly – the largest party in Scottish local government. They polled reasonably well everywhere and are represented on more local authorities than any other party. Their councillor numbers rose steeply in central Scotland and Glasgow as their long-established vote was at last rewarded with seats, although they could have done even better had they put up more candidates.

The Green Party won representation in Edinburgh and Glasgow, amounting to eight councillors in all, and were successful in attracting transfers. They were more successful than the rival socialist parties, which won a seat each and paid the price for the SSP/ Solidarity split. The role of Independent candidates also changed, with a decline in established areas like Highland where the parties started to offer candidates, but some growth in hitherto partydominated areas like Ayrshire

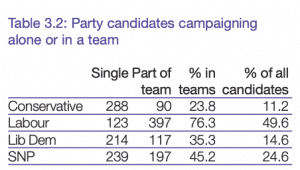

The change from FPTP in single-member wards to STV in wards of three and four members presented the parties with new circumstances: how they responded is examined in Chapter 3. Parties clearly wanted to nominate at least as many candidates as the number of seats they could reasonably hope to win, but nominating too many candidates could risk ‘leakage’, i.e. the transfer of surplus votes from their candidates to those of other parties.

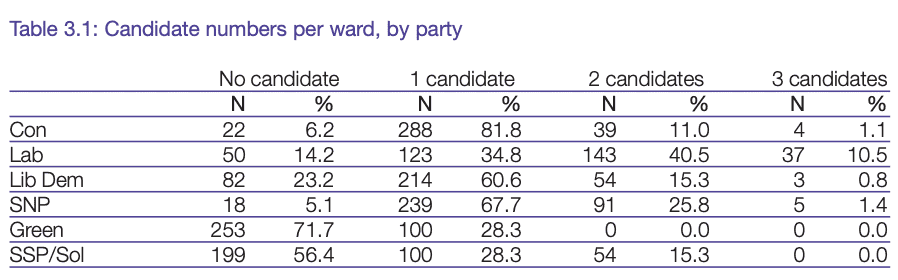

Labour nominated two or more candidates in just over half of the wards – as a result 76 per cent of their candidates were members of teams of candidates. The SNP, whose support is more evenly spread across the country, only nominated more than a single candidate in just over a quarter of all wards, resulting in most of their candidates campaigning on their own. With other parties, the nomination of more than one candidate in a ward was relatively rare.

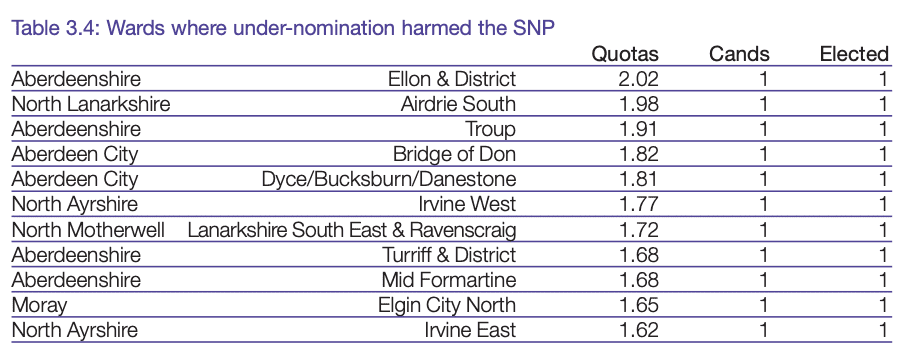

It appears that the SNP might have suffered in several wards by nominating too few candidates – with their level of support, which might not have been anticipated in all cases, it is probable that more candidates could have won them additional seats. Although in one ward Labour may have lost a seat through over-nominating, its strategy appears to have been effective.

Proportional voting systems are more likely to produce results that reflect not only the spread of political opinion but also social diversity. With systems that require parties to nominate a team of candidates rather than just one person, parties will have an incentive to nominate members who can appeal to all parts of society, thereby increasing the numbers of candidates from under-represented groups, such as women, young people and people from ethnic minorities. Chapter 4 examines whether the introduction of STV increased the diversity of those elected.

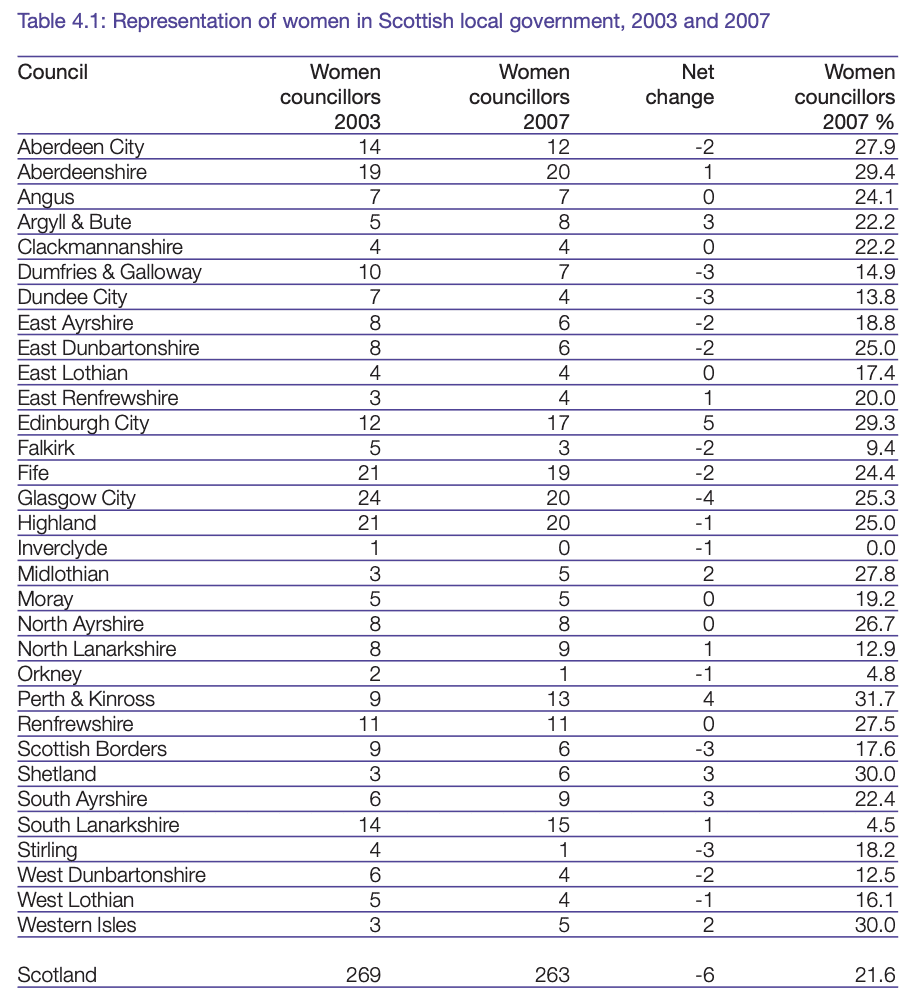

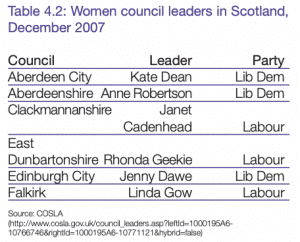

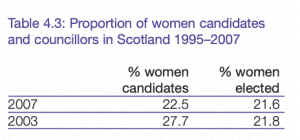

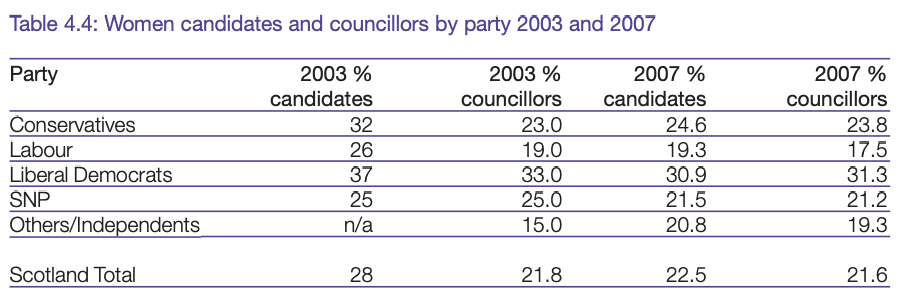

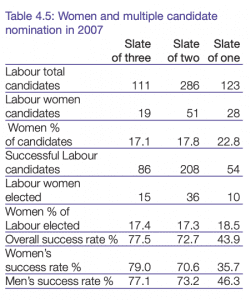

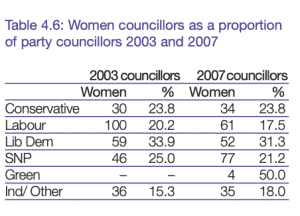

The analysis shows that little has changed as a result of the 2007 election. This, however, was not an unsatisfactory outcome as, prior to the election, there were fears that women, particularly in Labour, would suffer from the transition to the new system. With the move to three- and four-member wards, the number of candidates that the major parties would nominate would fall, and there was concern that women would lose out to male councillors with many years of service. Within all four major parties, the percentage of candidates who were women dropped in 2007, but while in 2003 many women may have fought in unwinnable seats, in 2007, with a system that makes the concept of ‘safe’ seats less valid, the success rate of women was comparable to that of men. As a result, the number of women councillors remained more or less the same – an outcome that should provide some optimism for progress in subsequent STV elections.

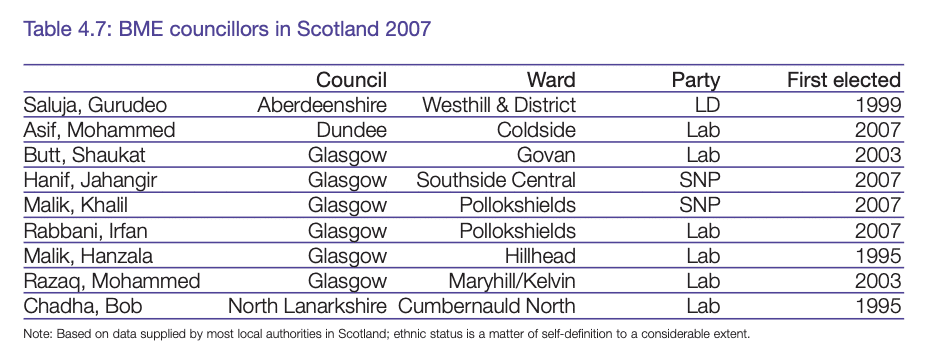

More young people were elected in 2007, and in particular there were three who benefited from the legislative change reducing the minimum age for candidates to 18. The number of black, minority and ethnic (BME) councillors remained unchanged.

Part 2: The voters’ experience

Chapter 5 describes how STV offered voters a more sophisticated choice in that they were able to rank candidates rather than just marking one with a cross. Moreover, because votes were transferable, voters were able to vote for the candidates they wanted without needing to worry about whether their votes would be wasted.

However, voters also had a much wider choice. The average number of candidates per ward rose from 3.4 in 2003 to 7.4. In the larger towns the major parties were able to put up candidates in most wards – a change from previous elections, in which there were many wards for which parties either could not find candidates or did not consider it worth putting up candidates. In Glasgow and Edinburgh the average number of candidates per ward rose above 9.

There were no uncontested seats in 2007, whereas in 2003, 61 councillors were ‘elected’ unopposed.

There were a few tightly fought wards in which the number of candidates was only slightly greater than the number of seats, making the outcome of the election more predictable, but the numbers did not compare with the high proportion of seats safe for one party or another in previous elections.

A very high percentage of voters ended up with a councillor for whom they had voted. In 2003 about half of all voters voted for losing candidates, but in 2007 nearly three-quarters found the candidate to whom they had given their first preference had been successful. To this total must be added those who voted for an unsuccessful candidate with their first preference but for a winner with a second or subsequent preference. Consequently, a large majority of voters have a councillor of their choice. This can only strengthen the link between councillors and their constituents.

For most voters, the 2007 election would have been their first experience of transferable voting. Consequently there were concerns that voters used to voting with a single cross, and in many cases being urged by parties to vote with just a ‘1’, would not take advantage of the extended choice offered by STV. The results for a first STV election were, however, remarkable.

Chapter 6 looks at the evidence from those local authorities that published information on voters’ preferences. It shows that the median voter cast three preferences. As there were very few cases in which a party nominated three candidates, this demonstrates that most voters gave support to candidates of at least two parties. The average number of preferences expressed in four-seat wards was higher than in those with only three seats, possibly a consequence of parties making more multiple nominations in the four-seat wards. Around one voter in five expressed only a single preference: this group will include those who failed to appreciate the change in system and used only a cross (deemed to be a valid first preference) and the numbers voting for only one candidate can be expected to decline in future elections.

Although, in the majority of cases, the three candidates who were ahead in three-member wards in terms of first preferences, and the four top candidates in four-member wards, ended up as winners, in 20.7 per cent of wards there was one candidate who leapfrogged over another with the help of transfers to win a seat, and in 29 of the 32 local authorities there was at least one case of a candidate overtaking another to win. Transfers were therefore important to the results of many wards.

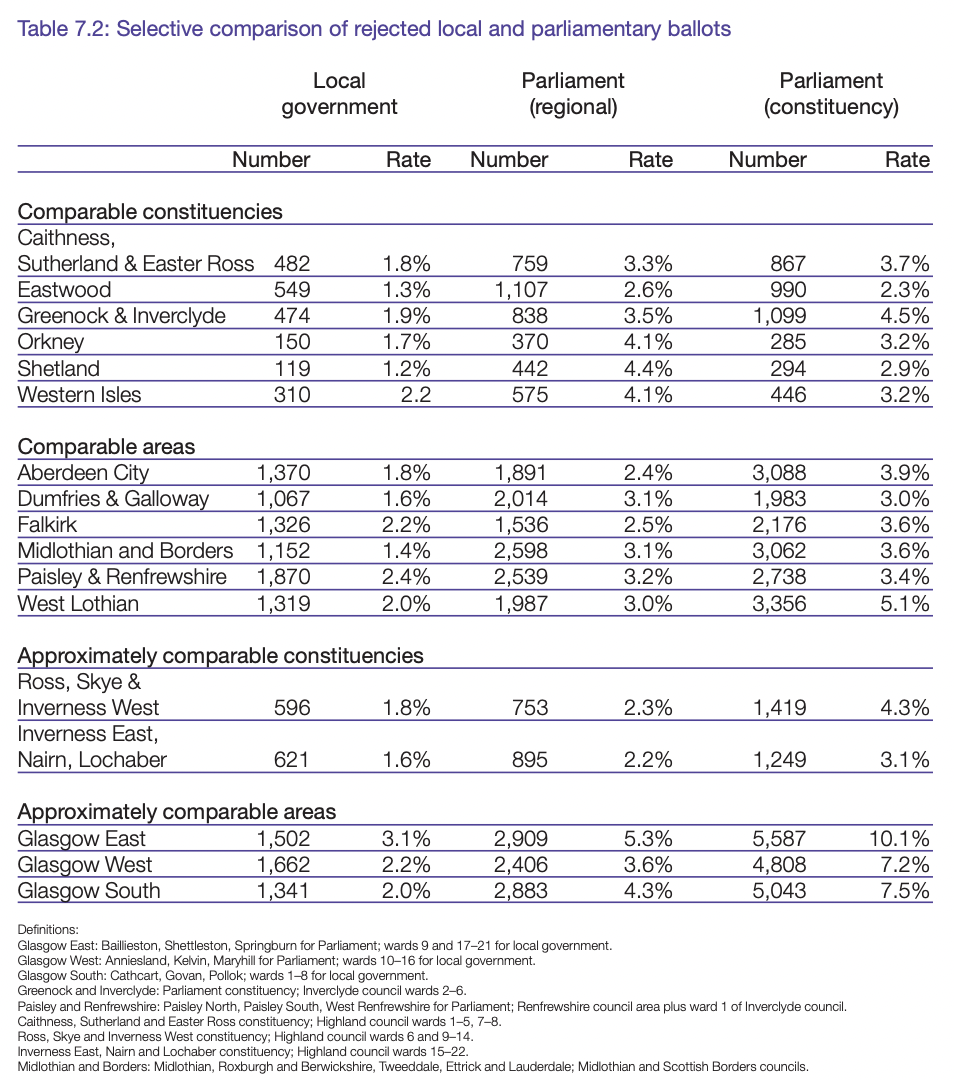

The local elections were held at the same time as the Scottish Parliament elections, following which the main media story – other than the success of the SNP – was the unacceptably high number of rejected ballot papers. However, Chapter 7 shows that across Scotland the rate of spoilt papers in the local government elections was very much lower than for the parliamentary election. While 1.85 per cent of local government ballots were spoilt, 4.07 per cent of the ballots for constituency candidates and 2.88 per cent for regional lists were spoilt in the parliamentary election

While any spoilt ballots are a cause for concern, the level in the local elections must be placed in perspective. More valid votes were cast than in the local elections of 2003, in spite of a new system being introduced for the first time requiring voting with numbers rather than a cross, and that was introduced alongside an existing X-voting system to which voters were accustomed. It therefore appears that, in general, voters did not have problems in adapting to STV.

Part 3: Election issues

This third part of the report considers some issues in the design of the election. Candidates were, as in previous elections, listed in alphabetical order and there is evidence that where parties nominated more than one candidate, the candidate placed higher on the ballot paper was advantaged over his or her running mates. Chapter 8 considers different options for ordering the ballot paper – random order, forms of rotation and the grouping of candidates by party – and proposes that these alternatives should be examined and, if appropriate, rigorously tested, before the next local government elections.

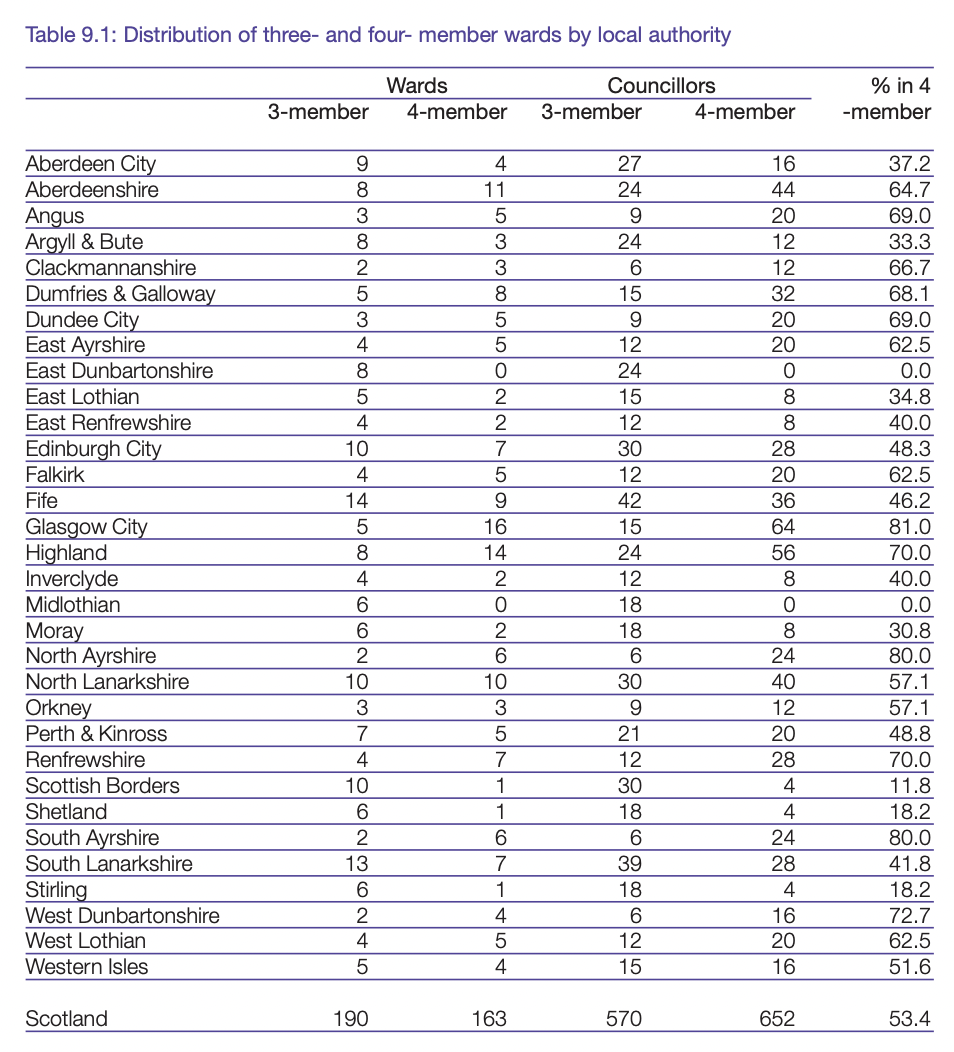

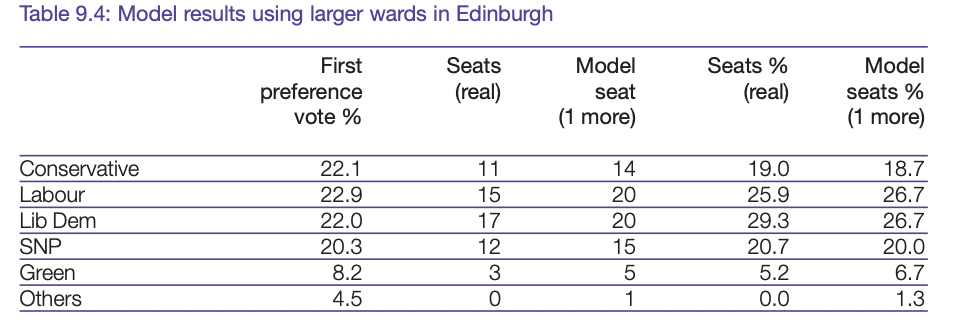

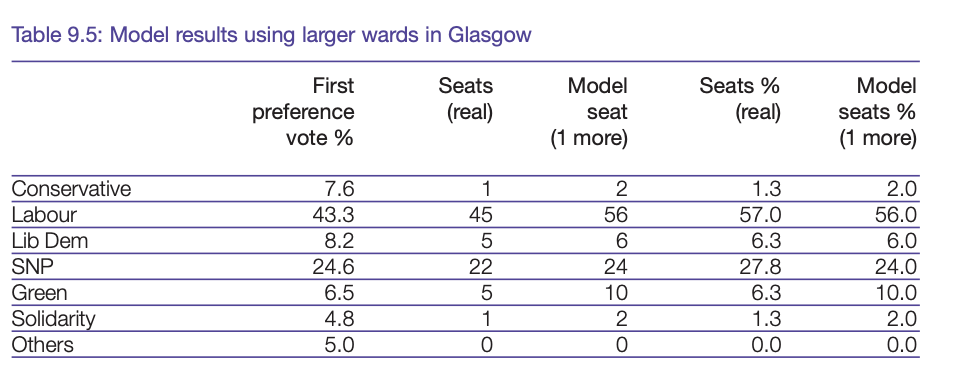

Chapter 9 considers the effects of the decision to divide Scotland into wards of three and four members for the implementation of STV. Although many argued for a wider range of ward sizes to make it easier to draw ward boundaries around what might be considered natural communities, there would appear to be only a very few cases in which boundaries seem to be clearly ‘unnatural’.

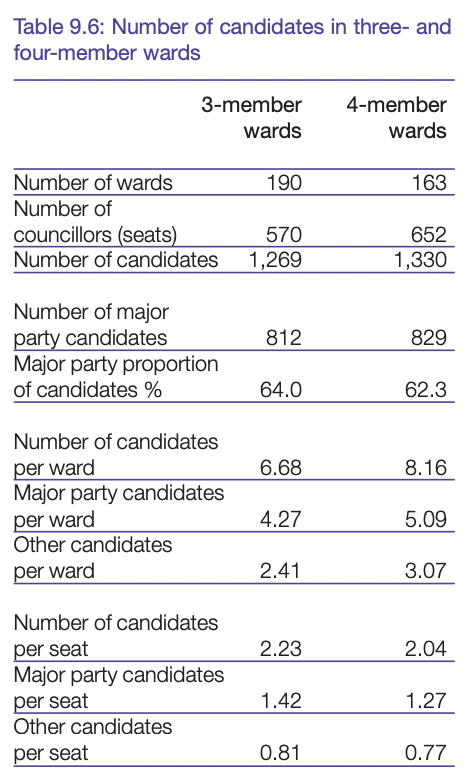

In total, there are 190 three-member wards and 163 with four members – as a consequence 53 per cent of councillors are in four-member wards. The mix of three- and four-member wards in different local authorities has been a consequence of the desire to create wards based on areas with defining characteristics – for example, there are urban areas where threemember wards are the norm and rural areas where four-member wards are common.

Larger ward sizes will give better protection against very disproportional results, but it remains the case that the ward sizes used produced a hugely more proportional result than would have been the case with the former First-Past-The-Post system, and it appears that the benefits of a move from 3- or 4- to 5- or 6-member wards would be slight.

In four-member wards, voters had a slightly wider choice of candidates than in threemember wards (8.16 to 6.68 on average). In four-member wards there was more chance of a major party putting up more than one candidate, thereby extending choice for party supporters. All but one of the minor party candidates (as opposed to Independents) were elected from four-member wards.

Part 4: Looking ahead

The final chapter concludes that the introduction of STV for Scotland’s local elections has been a success in that it has produced more representative councils, allowed voters to express their views on who they want to represent them in a more sophisticated way, and given most voters a councillor of their choice.

There is every reason to believe that future STV elections will build on this success. If, as appears likely, the local government elections are decoupled from those for the Scottish Parliament, voter information can be more focused on the use of transferable voting and election campaigns more focused on local issues. Now that the transition to STV has been made, we can hope to progress further towards councils that reflect the diversity of society and not just in terms of party support (although improvements will depend on parties’ approaches to candidate selection). The imperfections, albeit minor, in the alphabetical ordering of the ballot paper can surely be overcome before the next round of elections.

What remains to be seen now is how STV will, beyond elections, make democracy work better – how it will affect the way that councillors work and councils operate, and how it will change the way that electors and communities on the one hand and their elected representatives on the other relate. The Electoral Reform Society advocated STV not just to make electoral outcomes fairer, but because it believed that STV can, over time, change the way we conduct our politics, and these are issues that the Society will now be examining.

This report focuses on the 2007 elections for Scotland’s councils. The success of these elections points to the case for extending the use of STV to the parliamentary elections, and indeed to all elections in Scotland.

Part 1: What happened in the elections?

Chapter 1: Who won the council elections?

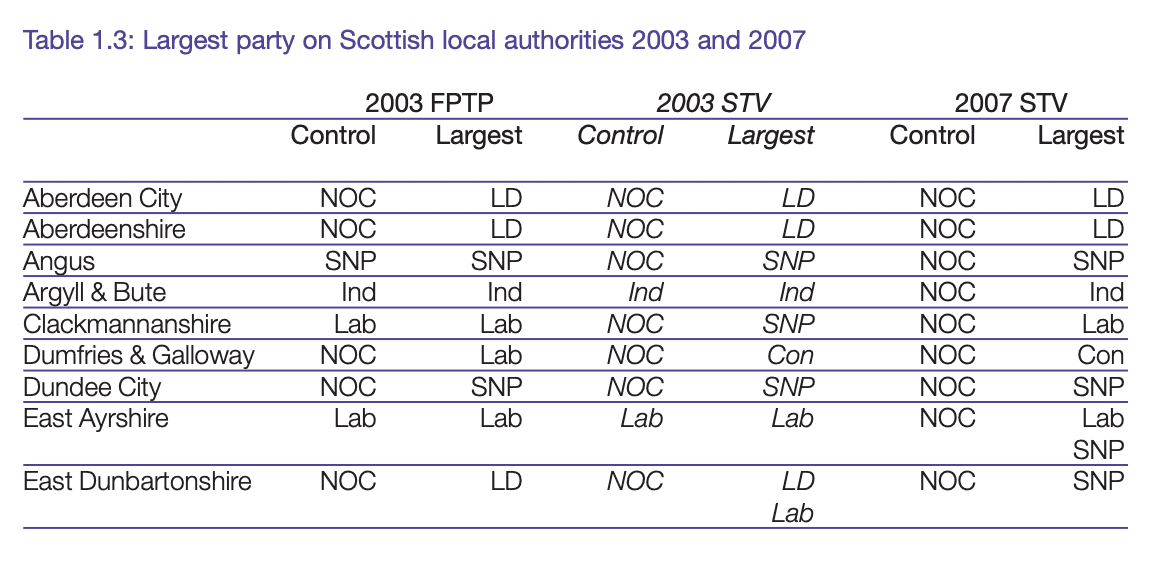

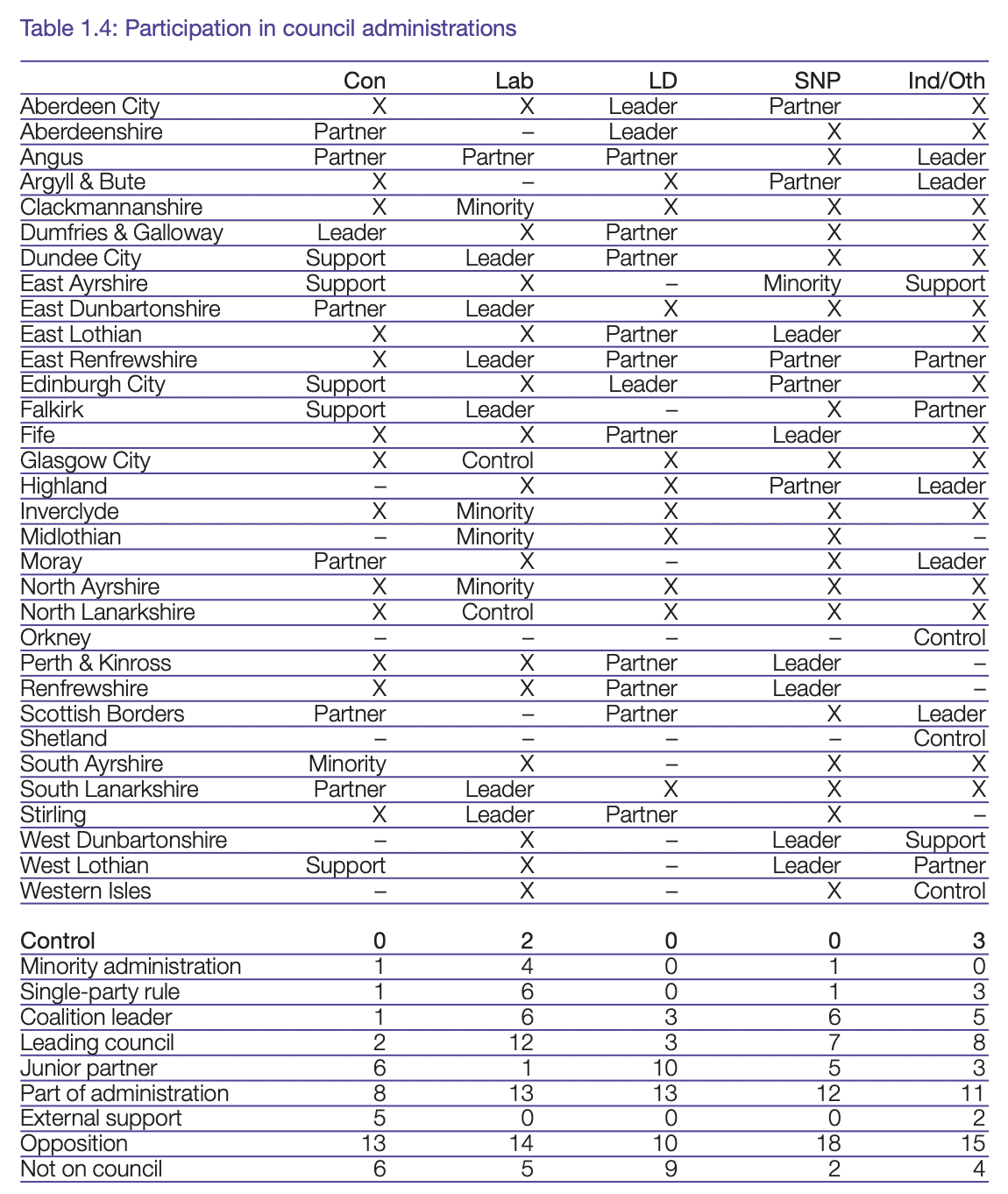

The 2007 STV elections produced 27 councils under no overall control. The exceptions were the three Independent Island authorities, plus Glasgow and North Lanarkshire where Labour retained a majority. Labour also won exactly half the seats in Midlothian and while this is technically no overall control, Labour has been able to form an administration with an effective majority on the casting vote. No other party achieved a majority anywhere.

Councillors elected: the facts

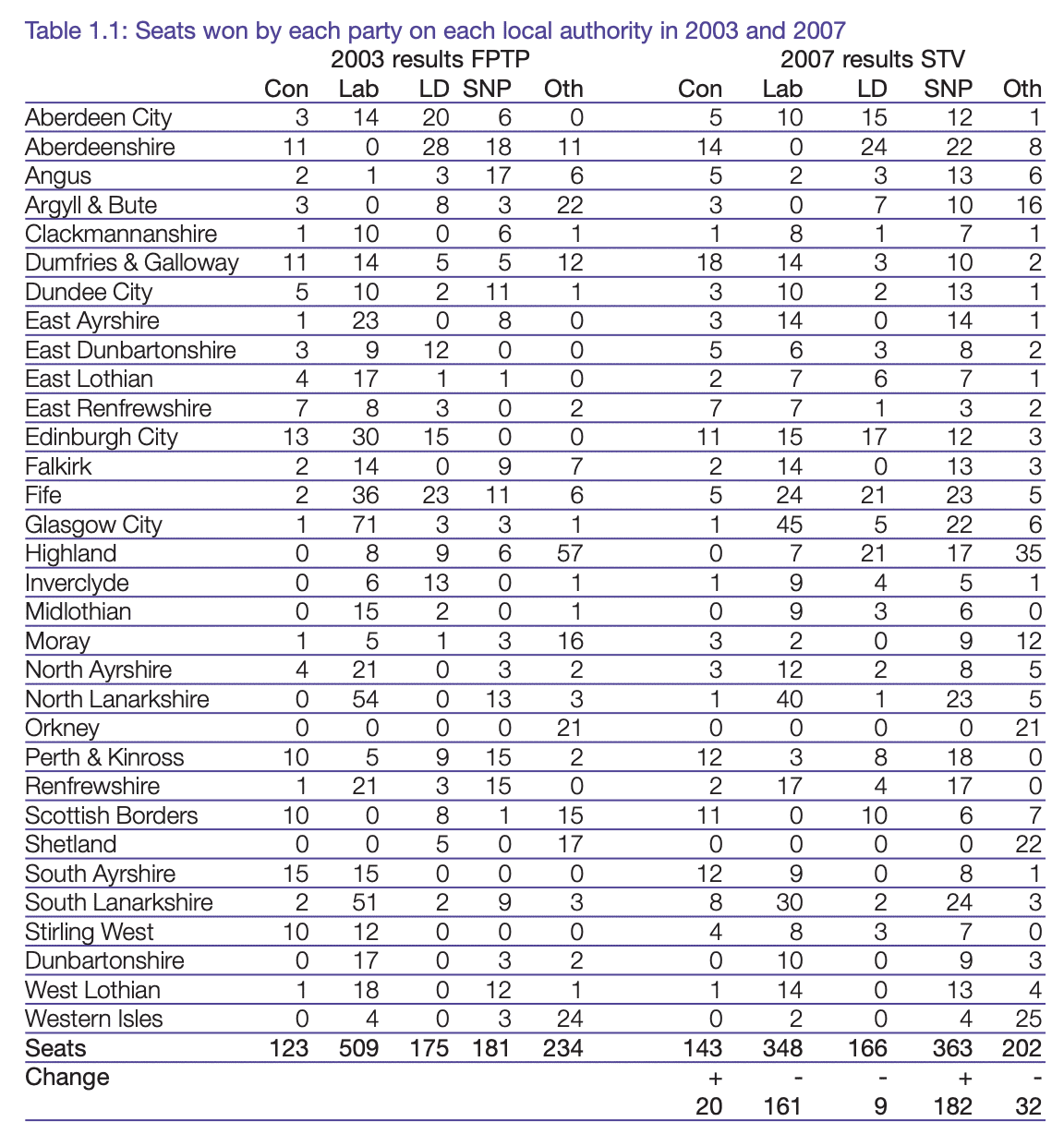

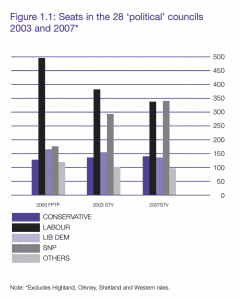

Compared to the FPTP result in 2003, therefore, the SNP made strong national net gains, very much at Labour’s expense. The Conservatives also advanced a little, and Independents and the Liberal Democrats slipped back. However, the contrast between these results conflates two separate sources of change – the new electoral system itself, and changes in what voters chose to do in 2003 and 2007.

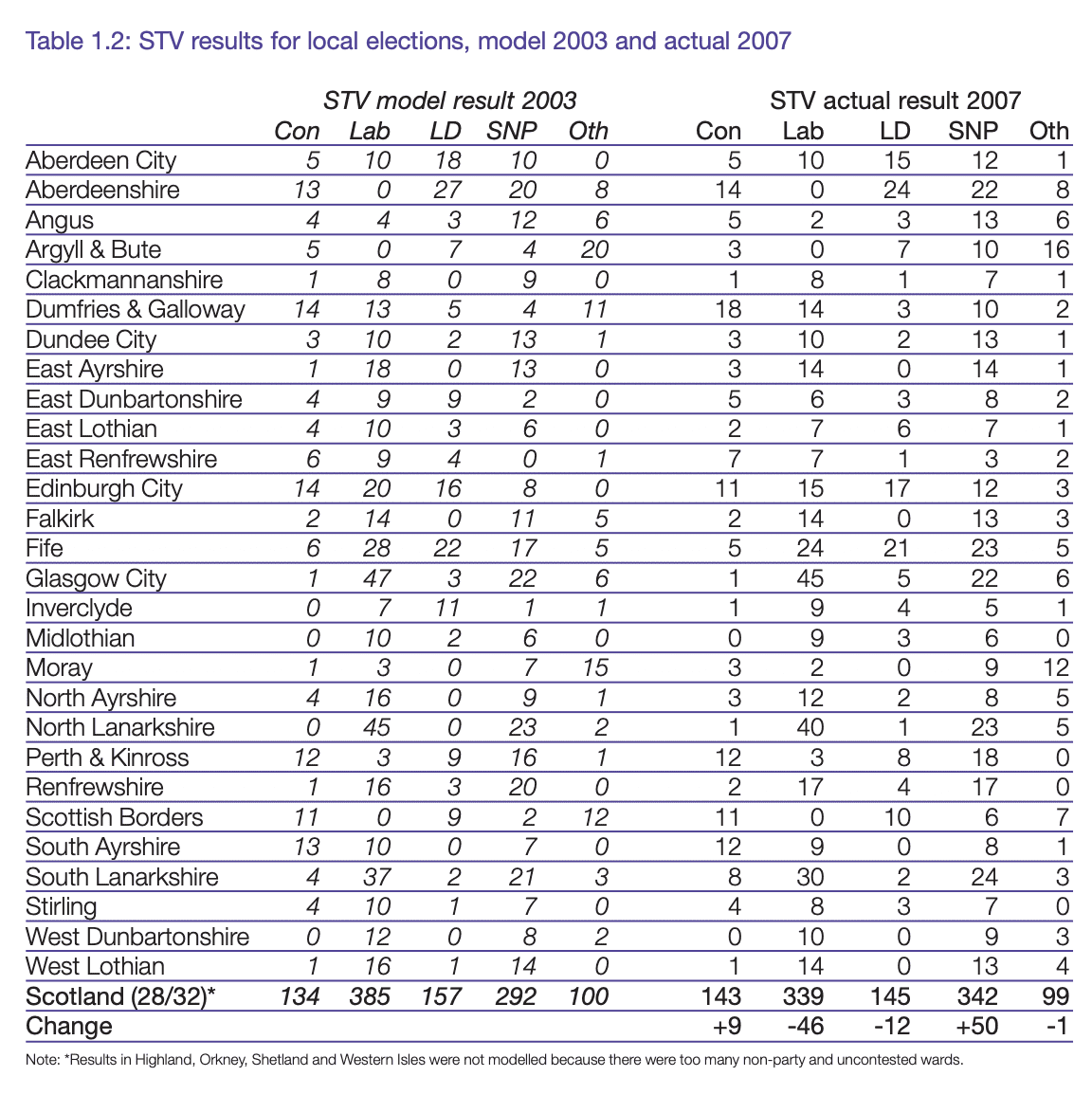

The ERS estimates of what would have happened under STV in 2003 are reproduced below, to show the extent to which there was a real change in party fortunes among the electorate in 2007. The results still show a clear national pattern of the SNP making gains from Labour.

Some of the most dramatic apparent changes since 2003 are almost entirely a correction to the previously very unrepresentative results of council elections, such as Labour winning 71 out of 79 seats in Glasgow on 47.6 per cent of the vote in 2003. Labour’s losses in Glasgow, compared with the notional STV result in 2003, are in fact quite minor. In Renfrewshire Labour actually did a little better in 2007 than it would have done under STV in 2003, despite being a few seats down on the actual FPTP result. In several authorities – such as North Ayrshire, Stirling and South Lanarkshire – Labour made large losses, both because of the system change and falling support. But the general pattern was for attrition of Labour strength from both sources.

Who runs Scotland’s councils?

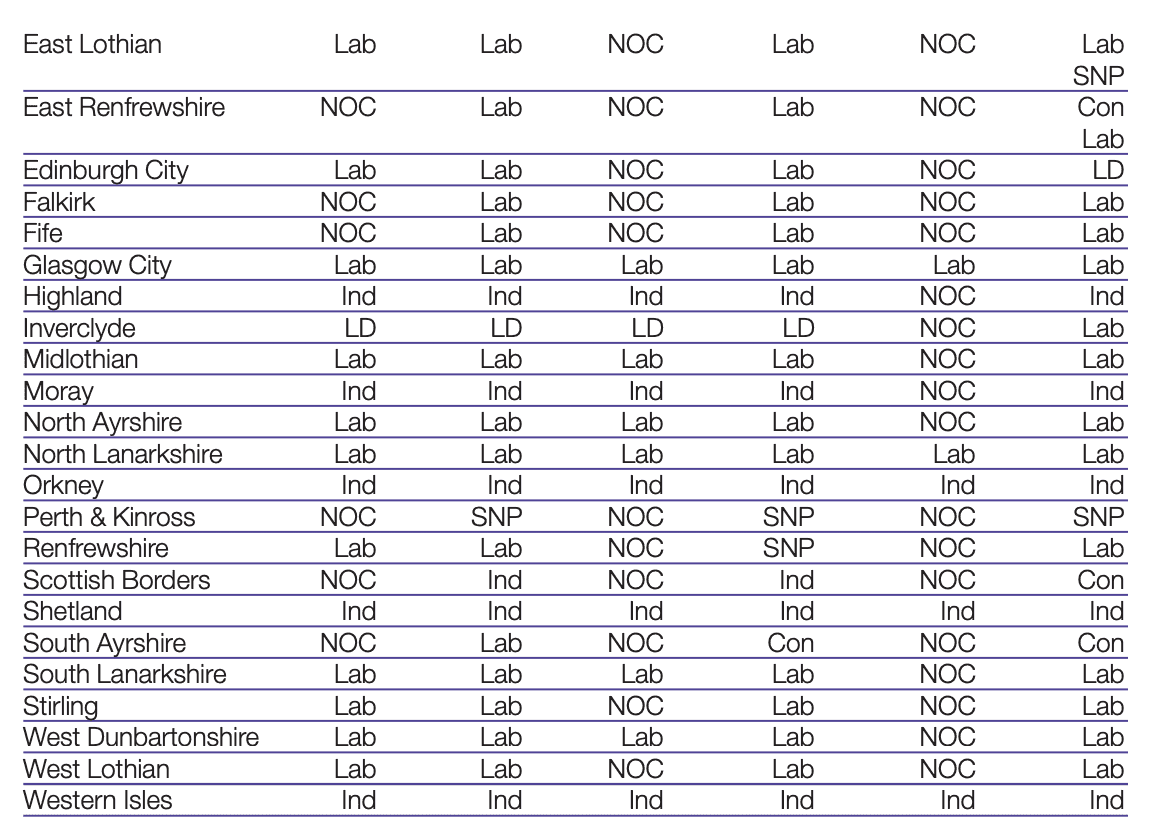

As there are now so many councils under no overall control, it is important to distinguish between the different configurations of no overall control (NOC), and how these shifted between 2003 and 2007.

When councils are under no overall control, a wide variety of governing arrangements can be made between different parties and independent candidates. This will no doubt emerge as a fruitful area for further research: seeing exactly how each administration has been formed, what forms agreements between parties take and what effect these arrangements have on policies pursued by the council.

How did the results differ from previous elections?

Compared to the 2003 FPTP results, Labour lost Clackmannanshire, East Lothian, Edinburgh, Renfrewshire, Stirling and West Lothian, and the SNP lost Angus (none of which would have been majority controlled under STV on the 2003 results). Labour also lost East Ayrshire, Midlothian, North Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire, and the Liberal Democrats lost Inverclyde, which would have been majority councils in 2003 under STV. The Conservatives also lost South Ayrshire, which they had controlled thanks to a by-election, and the Liberal Democrats lost their effective control over East Dunbartonshire.

Ever since the new local government structure was imposed in 1995, the major trend in Scottish local government has been for Labour to fall back from the high point reached in the 1995 elections, and for the number of councils under no overall control (NOC) to increase. In 1995 Labour controlled 20 out of 32 councils, which had fallen to 13 by the time of the last FPTP elections in 2003. Meanwhile, no other party had managed to replicate Labour’s dominance, and the number of ‘hung’ councils under no overall control rose from only three in 1995 to 11 in 2003. Five mainly rural councils remained with Independent majorities all the way through from 1995 (or 1994 in the case of the Island councils) to 2003.

There were 13 councils in which a party (as opposed to Independents collectively) won a majority of votes cast in 1995. The SNP topped 50 per cent in Angus, and Labour managed this in Clackmannanshire, Dundee, East Ayrshire, East Lothian, Falkirk, Glasgow, Midlothian, North Ayrshire, North Lanarkshire, South Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire. Labour’s dominance reflected the intense unpopularity of the Conservative government at the time, and the ascendancy of Labour as the party that was best placed to defeat the Conservatives.

By 2003 there was majority support for a party in only one local authority, namely Labourcontrolled North Lanarkshire, and all other council majorities depended on only a minority of votes cast. Labour ran Edinburgh on the basis of a little over one vote in four, with 27.4 per cent of the vote. Conservative popularity had not recovered much (outside the party’s target council of South Ayrshire) but Labour’s dominance was steadily eroded by the rise of the Liberal Democrats (Inverclyde) and the SNP (Renfrewshire, Dundee), and to some extent the growth of ex-Labour or anti-Labour Independents in central-belt authorities such as Falkirk.

The change to STV, comparing the real FPTP results with the notional STV results of 2003, would have translated this lack of majority support among the electorate into a larger number of councils under no overall control in 2003. The estimated results would have left Labour with seven councils (North Lanarkshire plus East Ayrshire, Glasgow, Midlothian, North Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire, where the party was either close to majority support or had a large lead over its nearest opponent) and the Liberal Democrats with one, Inverclyde.

Part of the reason for the decrease in singleparty dominance in local authority elections is to do with medium- and long-term political trends, such as the continuous slide in levels of support for the largest local parties since 1995 that has happened in both Scotland and England. If FPTP had been retained, the likely outcome of the local elections would have been a situation where the ruling party in most of Scotland’s councils had less than 40 per cent support from the local electorate. This situation would not be considered acceptable for the Scottish Parliament.

Another reason for the decline is the increased choice available in 2007 under STV. Voters had a wider range of candidates from which to choose than they did in 2003, and were also not constrained by considerations of tactical voting. Edinburgh voters, for instance, who had already showed considerable Green support in Scottish Parliament elections in 1999 and 2003, had the option of voting Green for the city council which they did not have in 2003.

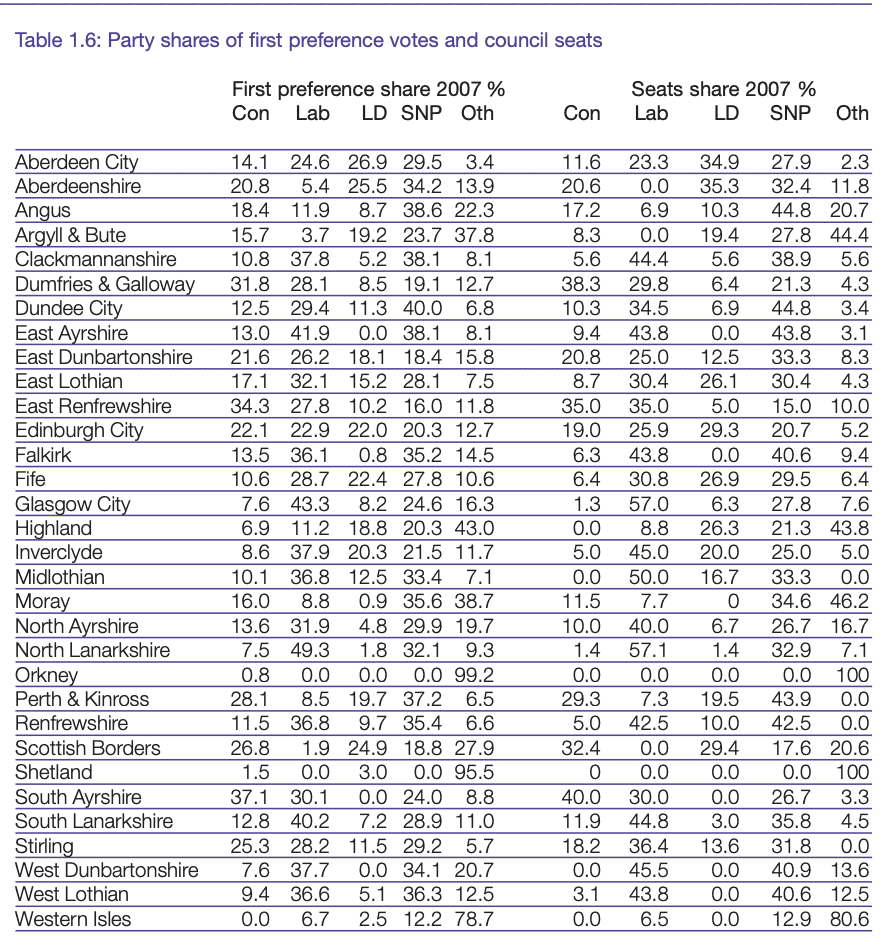

Did the results really represent how people voted?

STV delivered broadly proportional results in the elections to Scottish local authorities. The large proportion of councils under no overall control reflected the fact that no party polled a majority of first preference votes cast, although Labour fell only just short in North Lanarkshire. Independent candidates polled more than half the votes in the three Island authorities. In contrast to 2003 and previous local elections, it was rare for a party to score more than 40 per cent of first preferences. The only places where a party did this were:

- North Lanarkshire, Labour (49.3 per cent)

- Glasgow, Labour (43.3 per cent)

- East Ayrshire, Labour (41.9 per cent)

- South Lanarkshire, Labour (40.2 per cent)

In Dundee, the SNP won 39.97 per cent of first preferences, the highest share for any party other than Labour in any local authority.

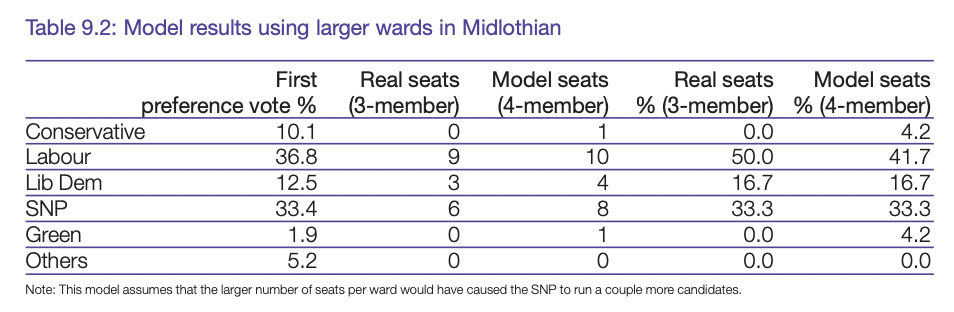

Where there was a significant body of voters choosing a party, that party received representation in the council chamber. The Midlothian Conservatives, who received 10.4 per cent of first preferences, were the largest unrepresented party. In contrast, in 2003 the SNP won 24.4 per cent of the vote in the same authority and won no seats. STV has brought such extreme distortions in the relationship of seats to votes to an end.

STV has also ended the egregious situation where a party can win a majority of seats on a very small share of the vote, as Labour managed in Edinburgh when less than 28 per cent of the vote sufficed to maintain overall control in 2003. STV has also prevented parties from winning overall control in authorities despite being outpolled by another party, as in Renfrewshire in 2003. More details of how STV has improved the representative quality of Scotland’s council chambers are available in the Appendix, which gives the election results council by council.

In comparing electoral systems, it is important to be aware that first preferences are not equivalent to FPTP votes. STV means that voters contribute more information about their choices than is possible under other systems. Take, for instance, two voters whose first choice is Green. Mr A is hostile to Labour and chooses the Liberal Democrats and SNP as his next preferences, ranking Labour at the bottom. Ms B is basically a Labour supporter, but knows the Green candidate and gives her a first preference and then votes Labour second.

Looking only at first preferences means that one assumes that the ‘votes’ of these people express the same political choice. If there are a lot more people who think like Mr A, as opposed to Ms B, then an STV election result will reflect this fact. This is why sometimes candidates with more first preference support lost out during the count to candidates who were more able to gather support from people who had made their first choice for another candidate. FPTP would not recognise any of these different political opinions, which electors were able to choose to express under STV, unless people felt forced to abandon their true party and vote tactically.

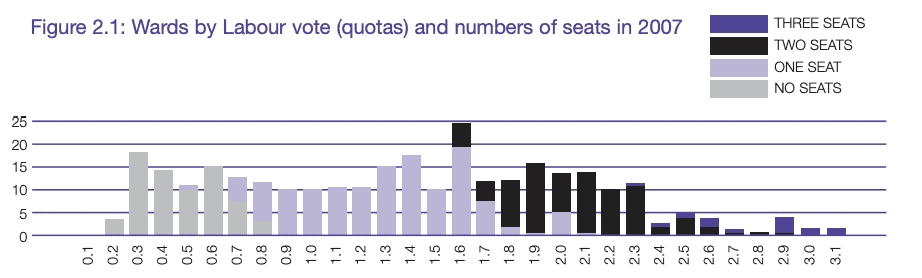

Parties and candidates vary in the extent to which they attract transfers, and this affects their share of seats. In some cases, parties (notably the SNP) did not stand enough candidates to win a proportional number of seats – simply put, you can’t win a seat if you don’t put up a candidate. Also, the largest party – particularly when the smaller parties represent very different alternative views – tends to enjoy something of a winner’s bonus. This helped Labour in Glasgow, where voters for other parties – Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, Greens, Socialists and others – often would not support each other’s candidates against Labour.

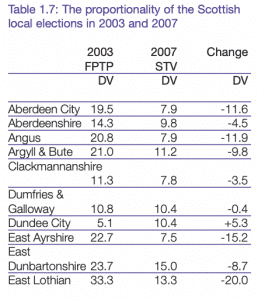

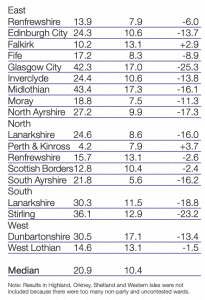

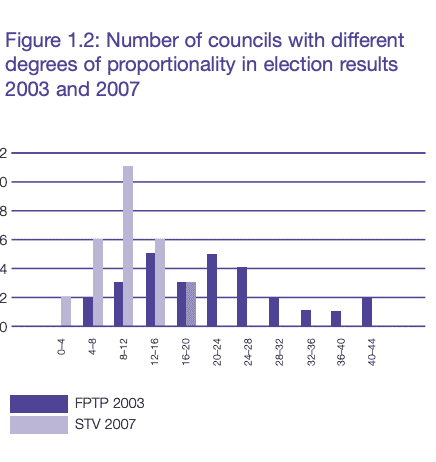

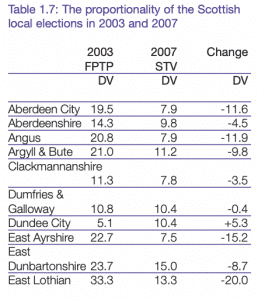

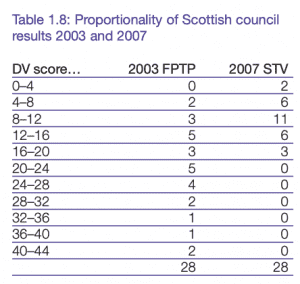

But the evidence for how well STV relates votes to seats is not just anecdotal – it can be demonstrated that the 2007 results were systematically not only more proportional than the 2003 FPTP results, but also achieved a very good relationship between seats and votes. One measure of how closely seats and votes are related is known as the ‘DV score’ (there is also a variant, DV-1, which excludes votes cast for the very smallest parties). The smaller the DV score, the closer the result in seats is to the votes cast by the electorate. The DV scores for the 2003 and 2007 local elections are given in the Table 1.7.

FPTP elections, as with Dundee in 2003, sometimes coincidentally give a proportional outcome in the manner of a stopped clock being right twice a day

The Scottish local government results suggest that even a relatively small-district form of STV is not only a considerably more representative system than FPTP, but also tends to produce more than just a reasonable concordance with voters’ first preferences. Dunleavy, Margetts and Weir (The Guide to Electoral Reform in Britain, Democratic Audit, 1998) refer to ‘the best European PR systems, which hit between 4–8% [sic]’ DV scores. In 8 of the 28 comparable results Scottish STV hit this benchmark or was even closer to strict proportionality (Moray DV score 3.3). The median DV score was only 10.4, not too far outside Dunleavy et al.’s range of very proportional scores, and the highest scores around 17 (by comparison, the FPTP results in 2003 had a median of 20.9 and the highest scores around 43, and the scores in UK general elections often exceed 20). Far from being only contingently proportional, STV seems systematically to give a pretty close relationship between party first preference votes and seats, even with small districts.

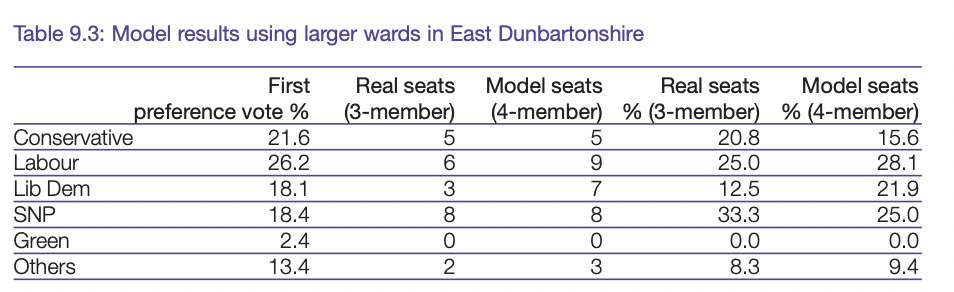

A limiting factor on proportionality is that STV involves voting in wards. Differences in the distribution of the vote, and turnout, can make a difference in any electoral system where voters are divided into districts, but much less so in STV than in FPTP. However, there are a couple of authorities where the way in which the wards were drawn up seems to have affected the proportionality of the overall result. The SNP in East Dunbartonshire had around 20 per cent in each ward – enough for one seat per ward with transfers in three-member wards, but if there had been four-member wards there was only enough support for a single SNP seat in each of those. The report deals in more detail with the issue of ward size in Chapter 9 below

Conclusion

The 2007 local authority elections in Scotland produced a large increase in the number of councils under no overall control. There were no councils where a party won a majority of the first preference vote (and few where anyone came close) and this was reflected in the election results as it had not been before. In two councils, North Lanarkshire and Glasgow, Labour polled strongly enough (over 43 per cent) to win overall majorities in these important authorities, something no other party managed despite 2007 being a low ebb of Labour support.

To some extent, the results were a consequence of the continuing decline in Labour’s share of the vote since the party’s high watermark in 1995, but the change in the system did cause a sudden and no doubt painful correction in many areas in which Labour had previously been over-represented.

The STV results were proportional to the votes cast in Scotland’s councils to a considerable degree. The Scottish local elections are evidence that, even with relatively small (three or four-member) wards, STV produces results that are an accurate reflection of the way people have voted.

The Appendix gives the detailed picture of how STV has worked in each local authority.

Chapter 2: The political parties and the local elections

Most local authorities in Scotland are structured on a party political basis – they are administered by parties or alliances of parties, most councillors owe allegiance to one or other party, and most votes are cast for candidates nominated by political parties. There are only three councils out of 32 in which party politics is not a significant factor, namely Orkney, Shetland and Western Isles.

Voters usually line up in a broadly similar way to the choices they make in other elections – particularly as in the last three sets of elections Scottish Parliament and local government voting has taken place at the same time. In 2007, as before, most parties ran an integrated campaign covering both the Scottish Parliament and local government elections. However, the range of choice of candidates on offer at the three levels of election (constituency, region and ward) is often different, which is reflected in different results.

Choice was usually most constrained at the constituency level, where minor parties tended not to stand, compared to a wide (but often ineffective) choice of regional lists and an intermediate (but perhaps more meaningful) amount for local elections.

Some voters also cast local election ballots on the basis of personal loyalty to one or more candidates, or on local issues to do with the performance of the council.

This chapter gives some information about the performance of the four major parties, some minor parties and Independents in the Scottish local elections.

The Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party

Candidates

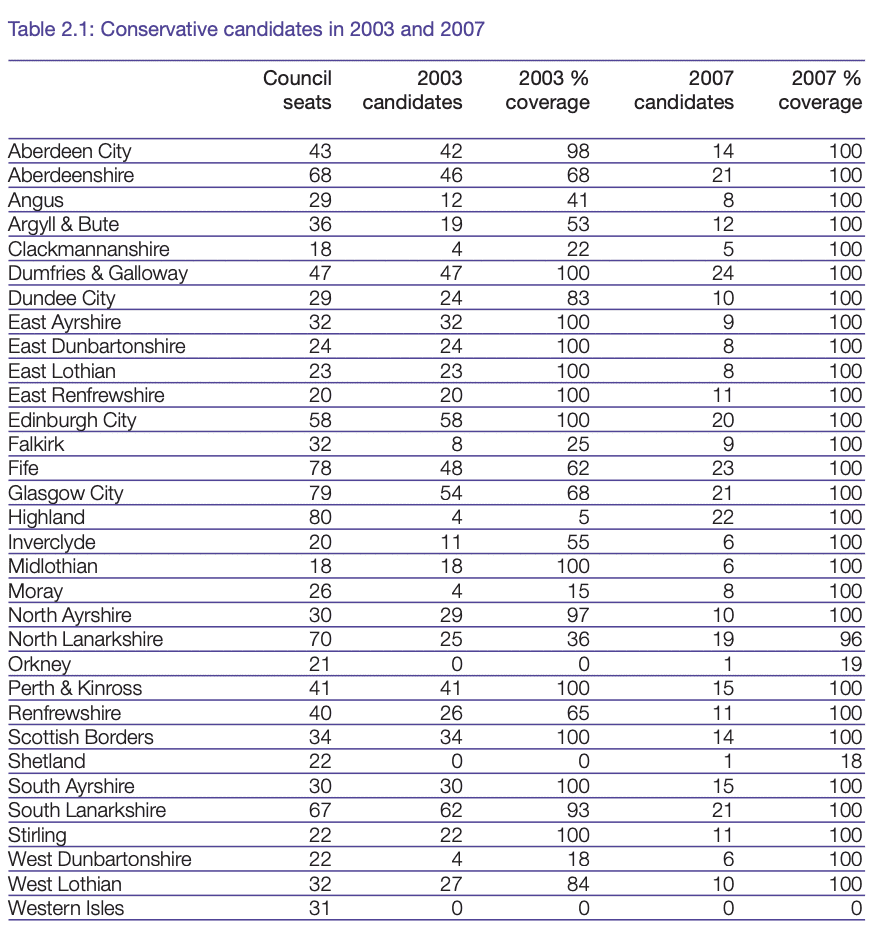

The new electoral system marked an important change in Conservative electoral strategy. The party stood candidates in every ward in mainland Scotland except one, the Fortissat ward of North Lanarkshire. In many areas this was a new development and a significant increase in voter choice. The Conservatives were the party that saw the biggest expansion in its reach in 2007.

There were broadly two types of area in which there had not previously been much Conservative activity in local elections. In some, such as Highland, the party has not put forward candidates much because Independents have dominated. In mainland rural areas the rise of the Conservatives and decline of old-style Independents has been taking place for years – for instance Dumfries & Galloway council has seen Conservatives entirely replacing Independents since 1995. The Conservatives have still, for the most part, kept out of elections for the three Island authorities. While the change in electoral system may have accelerated the pattern in some councils such as Moray and Highland, it is part of a long-term trend.

In other areas, the Conservatives were too weak in terms of organisation to find more than a few candidates, and generally also weak in electoral support, and did not run many candidates. Examples of this pattern include Falkirk, Inverclyde and West Dunbartonshire. There were also areas of large authorities such as Fife and Glasgow where Conservatives dared not tread. STV allowed the party to achieve complete coverage in such authorities, often with fewer candidates to find, and those candidates had more chance of electoral victory.

Results: votes

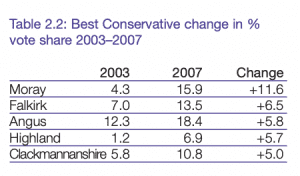

Across Scotland, the STV elections saw a small Conservative advance in votes (comparing first preferences in 2007 to votes in 2003). The 2007 elections, nationally, left the Conservative vote more or less where it was, but there were local variations. The biggest advances were usually in areas where there had been a large increase in the number of candidates – local election shares of the vote are determined by the parties’ supply of candidates as well as the voters’ demand for them.

In Moray and Angus, the increase in the Conservative vote since 2003 reflected the availability of more candidates in areas where Conservative potential was already apparent. In other areas, such as Clackmannanshire and Falkirk, it represented a foothold in areas where the party has not been a factor before – in those two authorities there had previously been a Labour–SNP contest that offered little to the Conservative-inclined.

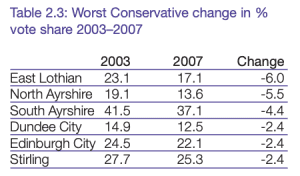

However, the Conservatives saw a decline in some areas where they had previously been part of a two-party system, notably in North and South Ayrshire.

In councils where there has been a longestablished pattern of multi-party competition, such as Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Stirling, there was little change in the Conservative share since 2003 (or previous elections). Taking the long view since 1995, the biggest Conservative increases in vote share were in several rural councils where Independent representation has been gradually displaced by party politics, such as Dumfries & Galloway (+21.6), Moray (+13.7), Scottish Borders (+12.0) and Aberdeenshire (+10.0).

Results: seats

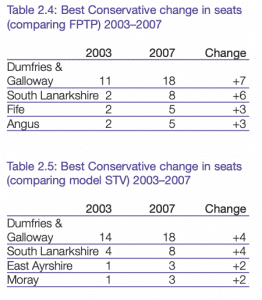

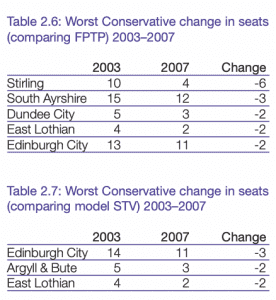

In terms of seats, the Conservatives were somewhat ahead of where they were in 2003, with a net gain of 20 seats from the FPTP results and nine compared to the STV model results.

South Lanarkshire and Dumfries & Galloway were the leading success stories under either measure, with gains of four seats in each council on the 2003 STV model results and six and seven seats compared to FPTP.

Edinburgh and East Lothian each saw the Conservative position slipping back most significantly when compared with the 2003 STV model results. Gains in some councils, such as Fife and South Lanarkshire, were mostly because the new system gave fairer representation to Conservative voters, while in others, such as Dundee, South Ayrshire and most spectacularly Stirling, Conservative losses were because they had previously been overrepresented.

As well as showing the flag, STV allowed the Conservatives to gain representation in some areas which have been almost entirely barren. Even under STV, the Conservative Party’s support is too low to hold out much hope of winning a council seat in many areas of urban central Scotland, but it does present possibilities that were lacking before. A minority Conservative vote has always existed in Scotland’s industrial heartland, providing a base of support, and the campaigning efforts of Conservative candidates, and sometimes the mistakes of other parties in nominating too few candidates, can allow victories in even the most unlikely sounding areas. The idea of the Tories having a representative for Motherwell South & Ravenscraig on North Lanarkshire council, for instance, is unfamiliar. In both North Lanarkshire and Inverclyde they won seats on councils which had no Conservative representation in 2003. The Conservatives also made something of a breakthrough in South Lanarkshire by returning a group of eight councillors compared to two in 2003, making up a significant group on the council which has successfully used its position to become part of the administration.

The Conservatives, like other parties, lost out in areas where they had previously relied on small areas of strong support to return knots of councillors. The Conservatives in Stirling had been dependent on rural wards, and in Dundee Broughty Ferry had provided a core of support that was enough to return several councillors. In each case they had to cede seats to other parties, but did not manage to expand their appeal into the rest of each authority. One of the consequences of STV is that each party is taken out of its previous comfort zones in searching out support. The Conservatives need to look at the 2007 experience in order to develop means of doing so.

Results: transfers

The Conservatives were consistently weak in picking up transfers from supporters of other parties (although they did rather better when votes were redistributed from small-c conservative independents). Labour and SNP voters in particular shunned Conservatives with Part 1 What happened in the elections? The political parties and the local elections Local authority elections in Scotland 3 May 2007 their lower preferences; it was rare for more than 7 per cent of transferred votes from these sources to end up with the Conservative candidate, but not uncommon for less than 3 per cent to do so (when there was still a reasonable number of parties left in the count). An interesting phenomenon with Conservatives receiving transfers was that they received more in areas where the Conservative first preference vote was relatively high. This may be an indication that the Conservative inclinations of an area feed through to lower preferences cast by supporters of other parties, or perhaps personal support for Conservative incumbents. It was striking that, for instance, the Conservatives picked up a reasonable share of Green and even Solidarity transfers in middle-class wards such as The Ferry in Dundee, and Colinton & Pentland Hills in Edinburgh.

The results of the Conservatives not being favoured for transfers was that the party’s candidates sometimes found themselves overhauled during the later stages of the count. Twenty-six Conservatives who looked as if they were in a winning position on the first stage of the count were overtaken by other candidates through transfers, while only two Conservatives managed to overtake someone else. If the Conservatives could overcome these negative views, the party would be much better placed to win STV elections. As it is, the party needs to get much closer to winning a whole quota (a quota is the share of the vote necessary to ensure a candidate’s election and is equivalent to 25 per cent in three-member wards and 20 per cent in four-member wards) in order to elect a candidate than the other main parties.

Results: councils

The Conservatives control no local authorities outright, and lost control of South Ayrshire, over which they exercised a tenuous grip for parts of the 2003–7 council term. However, Conservative councillors lead administrations in South Ayrshire as a minority, and Dumfries & Galloway in a coalition, and there are six more authorities in which the party is a junior partner in a coalition, in two of them (East Dunbartonshire and South Lanarkshire) in the unfamiliar role of working with Labour. In several other authorities, Conservative councillors have influence, either through informal support for another party’s administration or through the day-to-day negotiations that take place with minority government.

The Scottish Labour Party

Candidates

Labour nominated 920 candidates in 2003, with complete slates of candidates in 15 out of the 32 authorities. The party left only two councils, Orkney and Shetland, with no candidates at all.

In 2007 Labour put up 520 candidates. However, this covered a greater proportion of the Scottish electorate than in 2003. Twenty-two councils had complete slates, and the policy of not contesting elections in Orkney and Shetland continued. Other councils in which a majority of wards had no Labour candidate included Scottish Borders and Argyll & Bute. In all, only 50 out of 353 wards had no Labour candidate.

Labour was the party that had to deal most often with the issues involved with fielding multiple candidates in a ward. Just under half of all the incidences of multiple candidates involved Labour

Results: votes

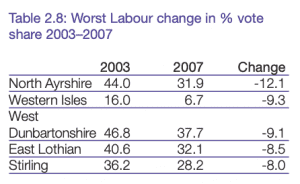

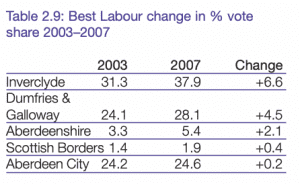

The 2007 elections were painful for Labour. Labour’s vote was down across nearly all of Scotland. Labour’s worst results, in terms of losing votes compared to 2003, came in a group of authorities in the west of Scotland, with North Ayrshire showing the largest drop (12.3 per cent) and several other authorities also contributing big drops (West Dunbartonshire, East Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire).

Ironically, two of Labour’s best results (Inverclyde and Renfrewshire) were in the same general area. East Lothian and Stirling also saw big drops in the Labour vote. These results reflected local issues (particularly in East Lothian and Inverclyde) and changes in the pattern of party competition (Stirling and South Lanarkshire may fall into this pattern, and Labour’s good result in Dumfries & Galloway was at the expense of the declining Independents).

Results: seats

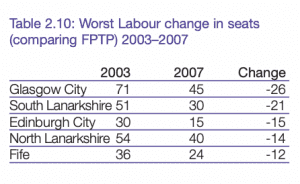

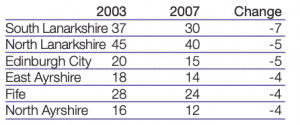

Labour had enjoyed over-representation in many Scottish councils for decades and had to undergo a large downsizing in one election. The damage was compounded by the adverse national climate in 2007, and by the willingness of other parties to cooperate and form administrations that exclude the Labour Party. Labour suffered severe losses of seats in the two big cities and the Lanarkshire conurbation, where the party had dominated.

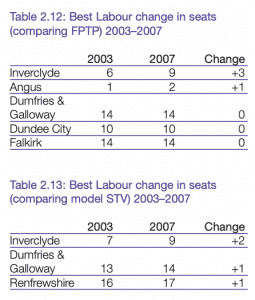

Even comparing the 2007 result with what would have happened in 2003 had STV been in use then, Labour still shed seats in Lanarkshire and a number of other urban authorities. It is worth noting that Glasgow, where Labour lost the most seats compared to the FPTP picture in 2003, was not among the worst results once the effect of electoral system change is accounted for.

Even in 2007 there were some local successes for Labour. Labour managed to gain some ground in Inverclyde, where the Liberal Democrats collapsed, and held steady in some other councils. In Dumfries & Galloway Labour continued its slow advance.

At ward level, the party now has a councillor in Newton Mearns South, an affluent ward in East Renfrewshire, and in East Sutherland & Edderton in Highland. The party now has footholds in the sorts of area where it never had a chance before, and future STV elections may see Labour expanding further into new areas.

Results: transfers

Labour could generally rely on electing a candidate with more than 0.67 of a quota in a ward. When votes were transferred from one Labour candidate to another during a count, either because of a surplus or a candidate being eliminated from the poll, there was quite a high degree of solidarity in the Labour vote. Between 60 and 80 per cent of Labour votes transferred to the Labour running mate, a finding that should cause some satisfaction to Labour’s campaign managers. The extent of leakage and the direction of transferred votes are fertile directions for future electoral research.

Labour lost rather more than it gained when one considers the cases where candidates overtook other candidates during the count to win a seat. There were eight cases where a Labour candidate managed this, but 25 when transferred votes worked against Labour. This was partly a function of the anti-Labour political climate of 2007, when the party was the incumbent at Westminster, Holyrood and very often the civic centre as well. This may be different in the next set of local elections and Labour might well be in a better position to attract transfers. In elections in which Labour is doing well, like the 1997 Westminster election or the 1995 local government elections, transfers would probably swing strongly towards Labour.

Results: councils

Labour retained control of two councils, Glasgow and North Lanarkshire, which are the only councils over which any party has majority control. Labour also has exactly half the seats in Midlothian. However, compared to the 2003 notional results under STV, Labour did lose control of East Ayrshire, Midlothian, North Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire. In addition, Labour lost Clackmannanshire, East Lothian, Edinburgh, Renfrewshire, Stirling and West Lothian which the party had won under FPTP in 2003.

However, having suffered these results in 2007 Labour remains a strong force on many local authorities in Scotland, with majority control in two powerful councils, and in four years’ time may well be in a position to move forward again. The party could reasonably hope to recover the five councils it might have won under STV in 2003, and also to develop strategies to broaden its appeal in other areas and run councils based on mass support from local electors rather than a trick of the FPTP electoral system.

Labour remains the party with the largest number of council leaders: 12 councils are led by Labour in a range of different types of administration, including majority, minority and coalition with a range of partners. In two councils Labour governs in coalition with its great UK rivals, the Conservatives; in one, East Renfrewshire, there is an agreement with its main rival in Scotland, the SNP.

The Scottish Liberal Democrats

The Liberal Democrats’ pattern of putting up candidates was patchier than that of the other parties. While they had complete coverage in areas of relative strength and the largest local authorities like Edinburgh and Glasgow, there was often incomplete coverage in other areas. In four local authorities (East Ayrshire, Orkney, South Ayrshire and West Dunbartonshire) the party ran no candidates at all.

Results: votes

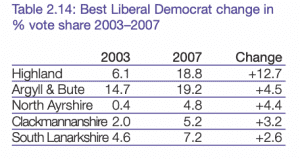

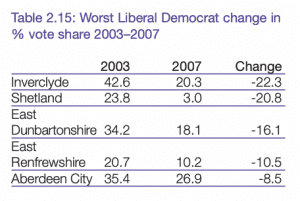

The Liberal Democrats, as in the Scottish Parliament election, had a disappointing overall result although there were some local causes for celebration. The party managed to squeeze into contention in several councils in which it had previously struggled to make an impact, such as North Ayrshire and South Lanarkshire. It also managed to attract extra support in some areas such as Highland and Argyll & Bute, in which Liberal Democrat voting is well established at Westminster and Scottish Parliament level but has hitherto not trickled down to local election voting.

However, the party also suffered some severe defeats, particularly in the two areas in which it had previously run the council, Inverclyde and East Dunbartonshire. The result in Inverclyde, where the party’s vote slumped 22.3 percentage points, was a much worse rebuff than any suffered by a Labour council. The local variation in the change in the Liberal Democrat vote was, by some margin, the largest of any of the four main parties.

Results: Seats

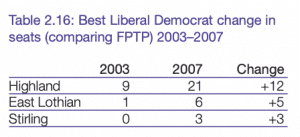

Highland topped the list of Liberal Democrat

gains, as political party candidates displaced

Independents. The party also did well in East

Lothian, where it had performed convincingly in

the 2005 Westminster election and had a

number of local issues to campaign on. The

Liberal Democrats also gained representation

in Stirling, which now seems to have vigorous

four-party politics.

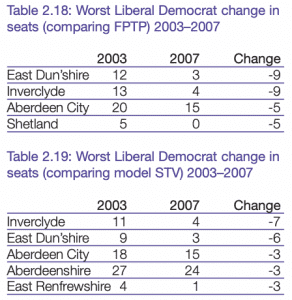

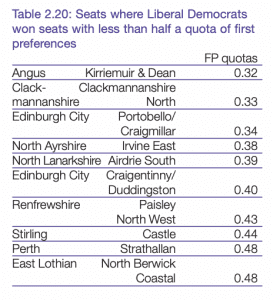

Inverclyde and East Dunbartonshire were again the worst areas in terms of seats, although Aberdeen (where the party had also had a leading role in recent years) saw a poor result as well. The party more or less withdrew from local politics in Shetland, causing a rather artificial drop in votes and seats.

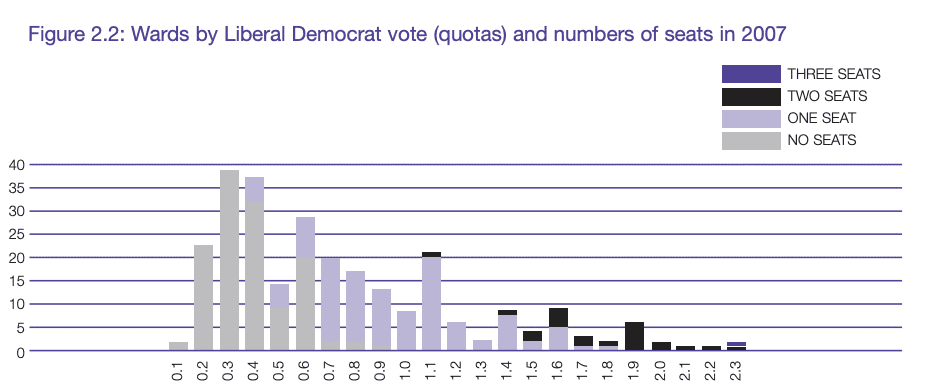

Results: transfers

The Liberal Democrats did well by attracting second preferences from people who had voted for other candidates. There were 31 cases, or 18.7 per cent of all the party’s councillors, where a Liberal Democrat candidate was not in a winning position at the first stage of the count but came through to win on transfers. This is a considerable strength for the party, and enabled it to win seats where it was well short of a full quota of first preferences.

The Liberal Democrats won 10 seats in which the party had less than half a quota of first preferences, and five in which it had less than 0.4 of a quota.

In most seats in which the party had more than 0.6 of a quota, it managed to win a seat, failing in only five out of the 49 wards with a vote of 0.6 to 0.9 quotas. The boundary was 0.6, below which the majority were not elected and above which the vast majority were. However, this strength is a potential source of future weakness, in that the party depends on the second preference support of people who are not strongly committed to it for many of its seats. The experience of the elections in East Dunbartonshire and Inverclyde shows that the electorate can sometimes turn violently against the party, and it is very vulnerable to any withdrawal of the general support and sympathy it enjoys from the Scottish electorate.

Results: councils

The Liberal Democrats lost their majority control of Inverclyde and their effective control of East Dunbartonshire. They retained their position as the largest single party in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire, and became the largest single party in Edinburgh. As well as Edinburgh, the party leads in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire and is a partner in administrations in 10 other councils, making it equal with Labour as the party most often found governing a local authority.

The Scottish National Party

Candidates

The SNP contested every seat in every authority in Scotland with the exception of the three Island authorities (no candidates in Shetland or Orkney, and four of the nine seats in the Western Isles). The SNP therefore had the most complete coverage of any of the Scottish parties, although it was running fewer candidates than Labour (433 to 520). The SNP ran more candidates than any other party in 2003, but in that case they were mostly ‘paper’ candidates with little chance of winning because of the FPTP electoral system.

Results: votes

The 2007 elections were a considerable success for the SNP in local government as well as for the Scottish Parliament. The party became the largest force in Scottish local government with 363 councillors (Labour returned 348). Labour actually polled slightly more first preference votes, but its advantage over the SNP was greatest in Glasgow and Edinburgh where wards are large, while the SNP did better in some areas with smaller wards.

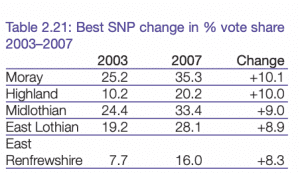

The rising SNP tide was relatively even across different local authorities. Its biggest growth since 2003 was in Highland and Moray, where it already has substantial support in Scottish Parliament elections but hitherto Independents have dominated in local elections (although in 1995 the SNP had won Moray). More directly political factors underlie its strong performance in East Lothian and Midlothian. In suburban East Renfrewshire, a marginal area between Labour and the Conservatives, the party had previously been very weak but broke through into contention in 2007.

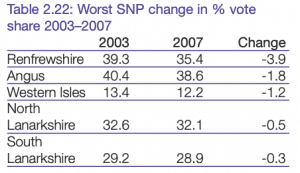

The SNP’s vote slipped a little in some of its strongest areas, particularly Renfrewshire and Angus. This reflects the more intense political competition from other parties in these councils – in Renfrewshire rather than a simple SNP v. Labour battle more voters had Conservative and Liberal Democrat options to choose, and some did so. The same is true in the Lanarkshire councils, where the SNP was previously the sole opposition to Labour in many wards.

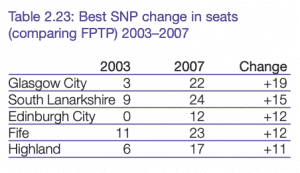

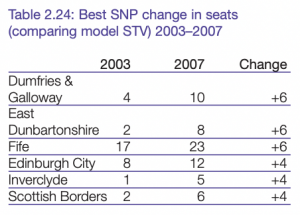

Results: seats

The SNP’s representation surged across urban Scotland, with striking gains in Glasgow and Edinburgh compared to the FPTP results in 2003. However, this basically reflected support that had always been there but had been denied representation by the electoral system.

The SNP made steady progress in the majority of local authorities, with good results in Dumfries & Galloway (despite its disappointment in the Scottish Parliament election in Galloway), East Dunbartonshire and Fife (where the party polled particularly well around Glenrothes, just as it was winning the Fife Central constituency)

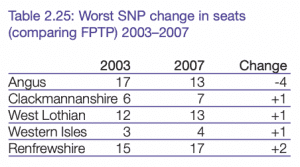

There was only one council with a net loss of SNP seats compared to 2003, and that was Angus where the SNP had previously had majority control. It is a common feature of FPTP election results that the leading party gets a disproportionate winner’s bonus, and Angus was a rare example of the SNP being favoured in this way by FPTP.

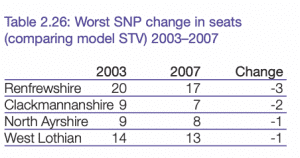

Compared with the national results in 2003, the SNP lost out in four councils, where smaller parties broke through in what had previously been two-party battles with Labour.

Results: transfers

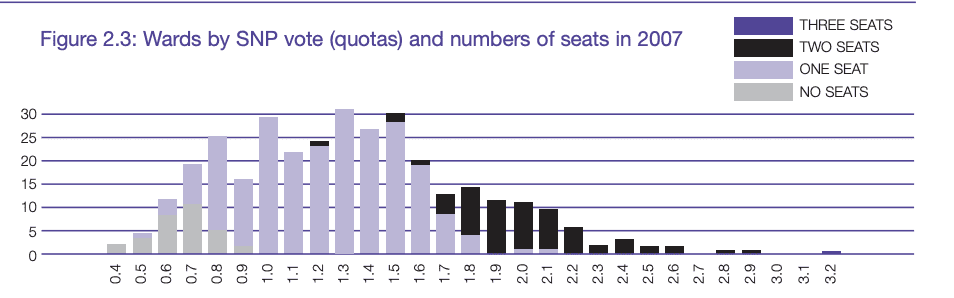

The SNP polled a reasonable proportion of the vote almost everywhere in Scotland (coming in below 0.4 of a quota in only two wards, Kelso & District in the Borders and Caol & Mallaig in Highland). It can reasonably said that there are no wards in Scotland (with the possible exception of the Island wards left uncontested in 2007) where the SNP, with a favourable national background and a good campaign, could not win a seat.

The even distribution of the party’s vote, with most wards in Scotland having 20–25 per cent voting SNP, was the principal reason why it was extremely under-represented under FPTP. However, under STV this was enough to win representation in most wards in Scotland

The SNP, like Labour, tended to be able to win the majority of seats in which it polled more than 0.67 of a quota. However, the SNP broke even on the number of candidates elected despite not starting the count in a winning position, with 14 overtaking others and 14 themselves being overtaken

Results: councils

The SNP does not have majority control of any authorities, having lost Angus in the 2007 elections. The SNP does run East Ayrshire as a single-party minority administration, and leads six councils where there is a coalition administration (four of them partnerships with the Liberal Democrats). In five more councils the SNP is a junior partner in running the council.

The Scottish Green Party

Candidates

No Green Party candidates stood in the local elections of 2003. The Green Party recognised that the electoral system was stacked against the party and, entirely rationally, concentrated its efforts on maximising its vote in the regional list ballot of the election for the Scottish Parliament.

In 2007 the Greens put up one candidate in each of 100 wards in 21 out of the 32 local authorities in Scotland. They offered complete slates in the big cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, and 15 in the 20 wards of South Lanarkshire. In other areas, Green candidates were more scattered, but there was a measure of coverage from North West and Central Sutherland in Highland to Annandale East in Dumfries & Galloway. The larger number of candidates was a response to the increased opportunities to elect councillors that the introduction of STV involved.

Results – votes, seats and transfers

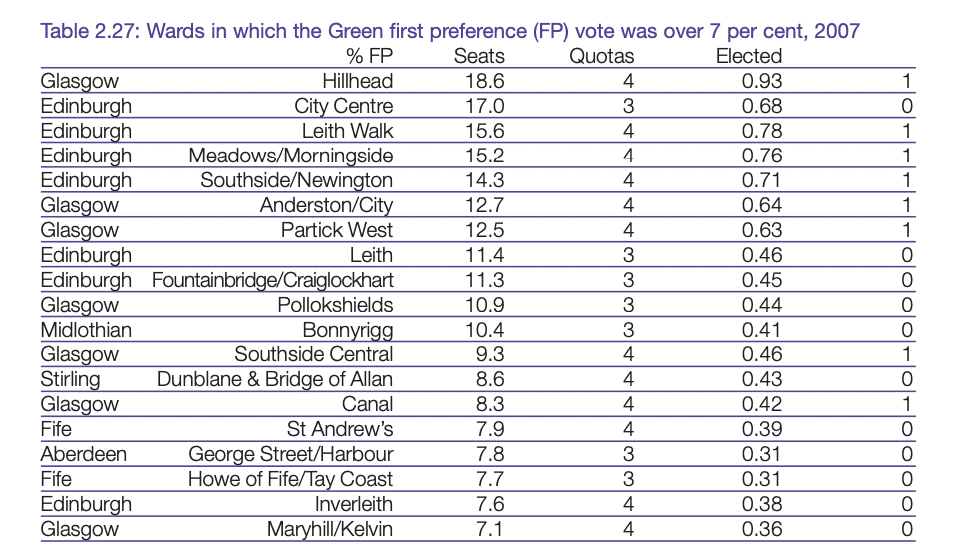

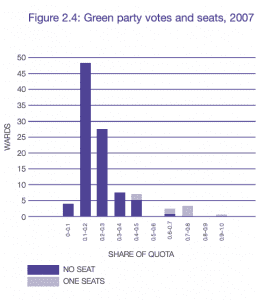

The 2007 elections saw the election of the first Green councillors in Scotland. Five candidates were successful in Glasgow and three in Edinburgh. Green candidates averaged 5.5 per cent of first preference votes, although this is composed of a large number of candidates with a share a little under this and a longer ‘tail’ of candidates winning a larger share. The following table lists the 19 wards in which the Greens polled more than 7 per cent of the vote.

The Greens won every seat in which they won more than 0.45 of a quota in four-member wards (and one with 0.42 of a quota thanks to SNP under-nomination and a large SNP surplus that helped the Greens), but no seats (even with 0.68 of a quota, or 17 per cent, in Edinburgh City Centre) in any three-member wards.

The Greens’ ability to win seats without a full quota of first preference support anywhere indicates their transfer-friendliness, i.e. their ability to attract second and lower preferences from supporters of other candidates or parties. In Edinburgh, Greens benefited from fairly strong transfers from the two socialist parties (25 per cent from Solidarity and 32 per cent from the SSP), whose candidates were usually eliminated early in the count. They also gained transfers from all the other parties, particularly in cases where there were no candidates from the same party available to receive transfers

The Greens could even make significant inroads in a few cases where there were party colleagues ready to receive the transfer, as in Meadows/Morningside where only 54.5 per cent of a Liberal Democrat surplus was transferred to the running mate and 16.5 per cent leaked to the Green. This might suggest that Greens can profitably appeal for second preference support from identified supporters of other parties, and perhaps particularly to people who have a personal identification with a candidate but not necessarily his or her party.

However, the party’s fairly low share of the vote, at least in the circumstances of 2007, means that it will have difficulty reaching the threshold imposed by three- and fourmember seats, even with good inward transfers. To elect a candidate with 5.5 per cent of the vote, assuming that half a quota is going to be enough, would require eightmember seats, which most people would consider too large.

While an increase in the average size of a ward will lower the barriers a bit, the Greens still need more electoral support if they are to win more seats. To elect the 19 candidates who polled over 7 per cent would require sixmember wards at the very least. Increasing ward size would also involve larger wards being the units, and in many cases outside the big cities this would mean diluting areas of Green strength (such as Dunblane/Bridge of Allan) with surrounding, weaker territory – or imposing considerable demands on campaigners who will have to cover a large area.

In the short term, and almost certainly the long term as well, a Green strategy to win more councillors is going to require targeted campaigning to convert points of existing strength into areas with Green councillors. Some of these areas, such as Dunblane and St Andrew’s, are four-member wards. While the seats the party narrowly missed in Edinburgh (City Centre, Leith) and Glasgow (Pollokshields) have three members, the credibility and resources from having a group of councillors from other wards may help the Greens win more seats, perhaps even threemember seats, in Glasgow and Edinburgh, just as their initial breakthrough in the 1999 Scottish Parliament election led to more gains in 2003.

The Scottish Socialist Party and Solidarity

The position of the socialist parties in the runup to the 2007 elections was not strong. The 2003 elections for the Scottish Parliament were a considerable success for the Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) under Tommy Sheridan. The party won six regional seats in the Scottish Parliament. However, success in the local elections was limited, in considerable measure because of the FPTP electoral system that prevented the party from translating a respectable share of the vote in Glasgow into many seats. The SSP won a single seat in Glasgow and also one in West Dunbartonshire. Under STV, the ERS estimate is that the SSP would have won six seats in Glasgow in 2003, and was not too far behind winning several more. But the party split in 2006, with Sheridan leading a breakaway party named Solidarity, and its vote was squeezed by the rise of the SNP as the May 2007 elections approached.

Candidates

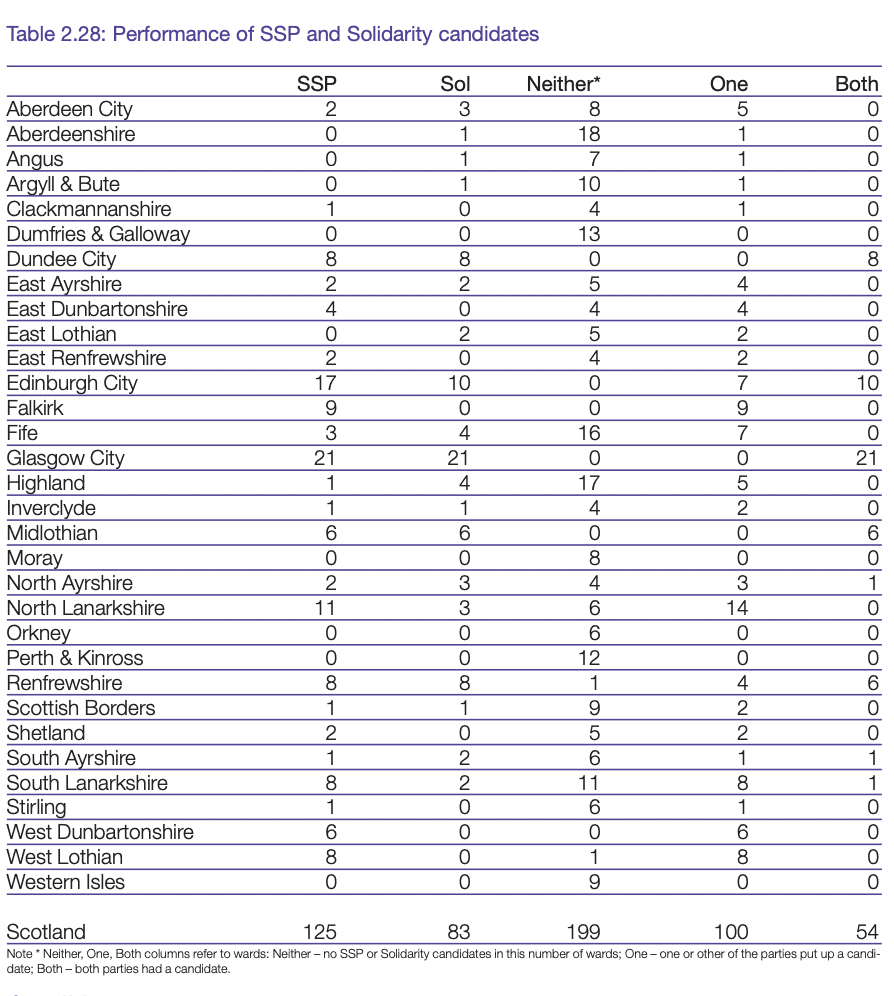

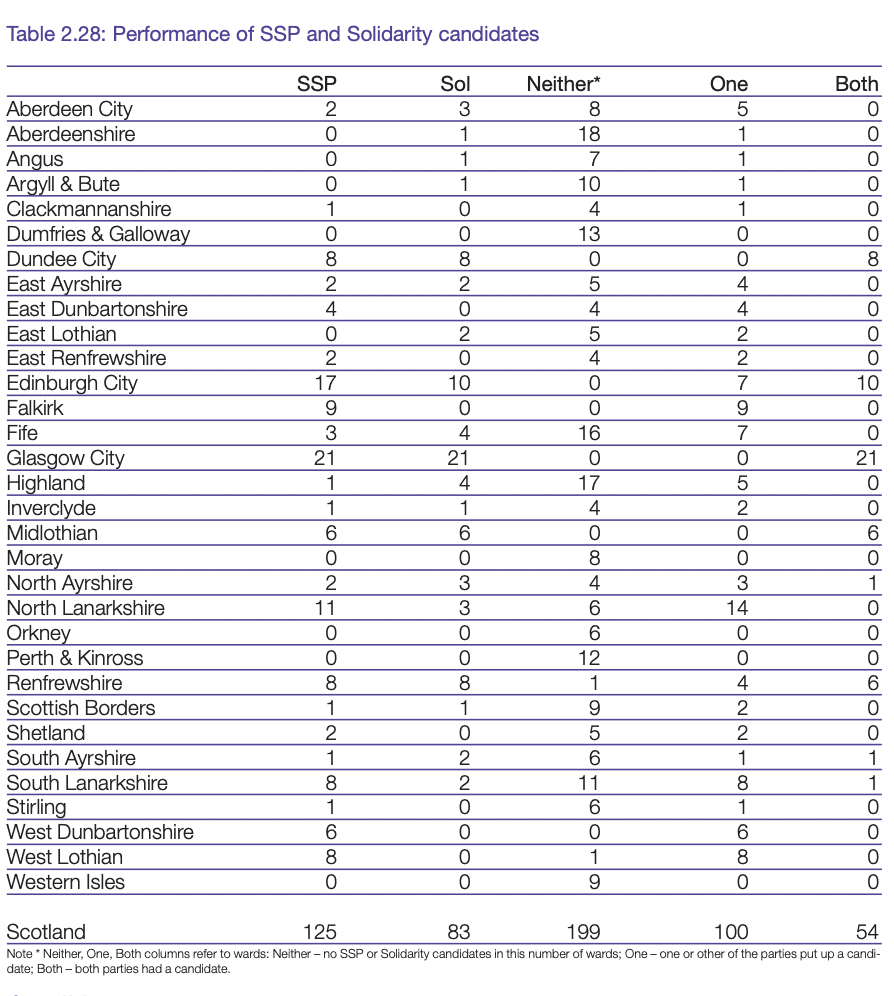

The pattern of candidates varied in different areas. Some had no socialist candidates at all (Dumfries & Galloway, Moray, Orkney, Perth & Kinross and Western Isles). In Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Midlothian, voters in every ward had a choice between SSP and Solidarity. These four councils accounted for the vast majority of the 54 wards where the parties fought each other. In other areas (such as North Lanarkshire) either different wards had gone different ways in the party split or a local deal had been done. Other branches of the former SSP seem to have gone entirely for one or other of the successor parties (the SSP in West Dunbartonshire and West Lothian, and Solidarity in most of Highland). There were 100 wards where one party but not the other stood. Overall, most wards in Scotland (199) had neither SSP nor Solidarity on the local ballot.

Results – votes

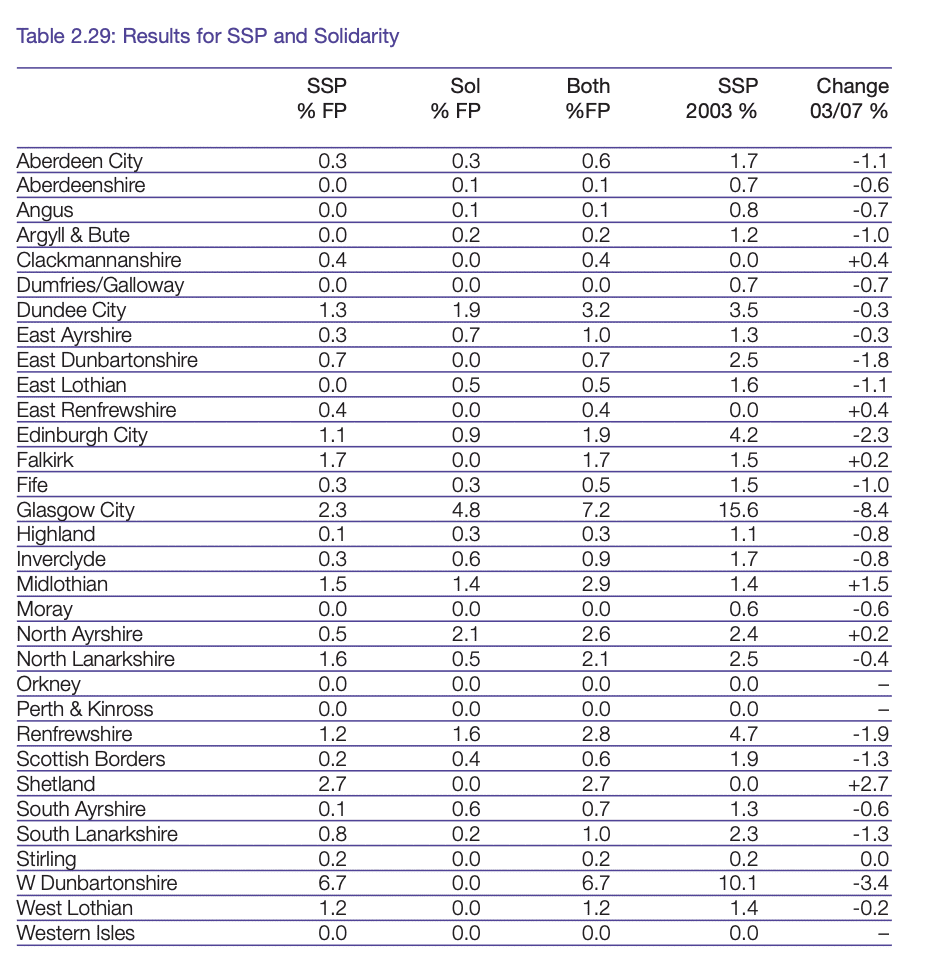

The 2007 elections were generally very poor for the two socialist parties. Compared to how the 2003 elections would have looked under STV, they ‘lost’ five seats in Glasgow. In most wards outside Glasgow (and a couple of other towns such as, perhaps surprisingly, Lerwick and Irvine) their share of the vote was almost negligible. Most of the few apparent gains came from increased availability of candidates rather than greater popularity. There was not a great deal to choose between the electoral fortunes of the two parties, save that in Glasgow Solidarity did rather better, helped by Tommy Sheridan’s nearly successful bid to retain his Scottish Parliament seat. The following table lists the 16 cases where an SSP or Solidarity candidate obtained 5 per cent or more of first preferences.

The combined socialist total in the Greater Pollok ward of Glasgow was 14.1 per cent, putting it in second, behind Leven, in its support for the small left-wing parties; Craigton’s combined total was 13.1 per cent. Pollok was the only ward in which a large socialist vote was split more or less evenly between two rival candidates, although in East Centre ward in Glasgow the combined vote was also relatively high at 9.7 per cent.

The socialist vote in 2007 was generally too small to put a candidate in contention for a seat, and would still be too small even if wards were electing more than 3–4 councillors. Most SSP or Solidarity candidates would need to get close to or over the quota to be elected because their parties do not attract many transfers. Ruth Black was, however, the beneficiary of 18.5 per cent of a large SNP surplus that had no SNP candidate to go to – although even so she was elected last, without having reached a quota.

The chances of a seat in Pollok were, however, wrecked by the party split and the extreme reluctance of supporters of the SSP and Solidarity to give the other party their second preferences. When SSP councillor Keith Baldassara was eliminated in the Pollok count, only 28.4 per cent of his votes transferred to Alice Sheridan of Solidarity. Nor was this a freak result of local circumstances – transfer rates of around 25 per cent between the two parties were typical. The bitterness between the parties’ leaders seems to be reflected among their voters. While a unified SSP would have been a significant force at least in Glasgow in the 2003 local elections, falling support and the split have relegated the far left to the fringes of Scottish politics.

Results – seats

Two candidates were elected from the socialist parties. A well established SSP councillor in West Dunbartonshire, Jim Bollan, was reelected in the Leven ward with an impressive vote, clearing the quota in a four-member ward and therefore winning before any votes were transferred. The Vale of Leven has long been known for its working-class socialist politics.

The other successful candidate was Ruth Black, who was elected for Solidarity in the Craigton ward in south-west Glasgow. Craigton and Pollok have a recent history of left-wing politics associated with Tommy Sheridan (elected in the areas as a Scottish Militant Labour candidate in 1992).

Some candidates elected as Independents, particularly in Fife, had decidedly left-wing politics (like Willie Clarke, formerly a Communist, who was elected with 95 per cent of the vote in Lochgelly in 2003 and easily passed the quota in The Lochs in 2007). However, the Fife left is separate from the warring SSP and Solidarity forces

Independents and Others

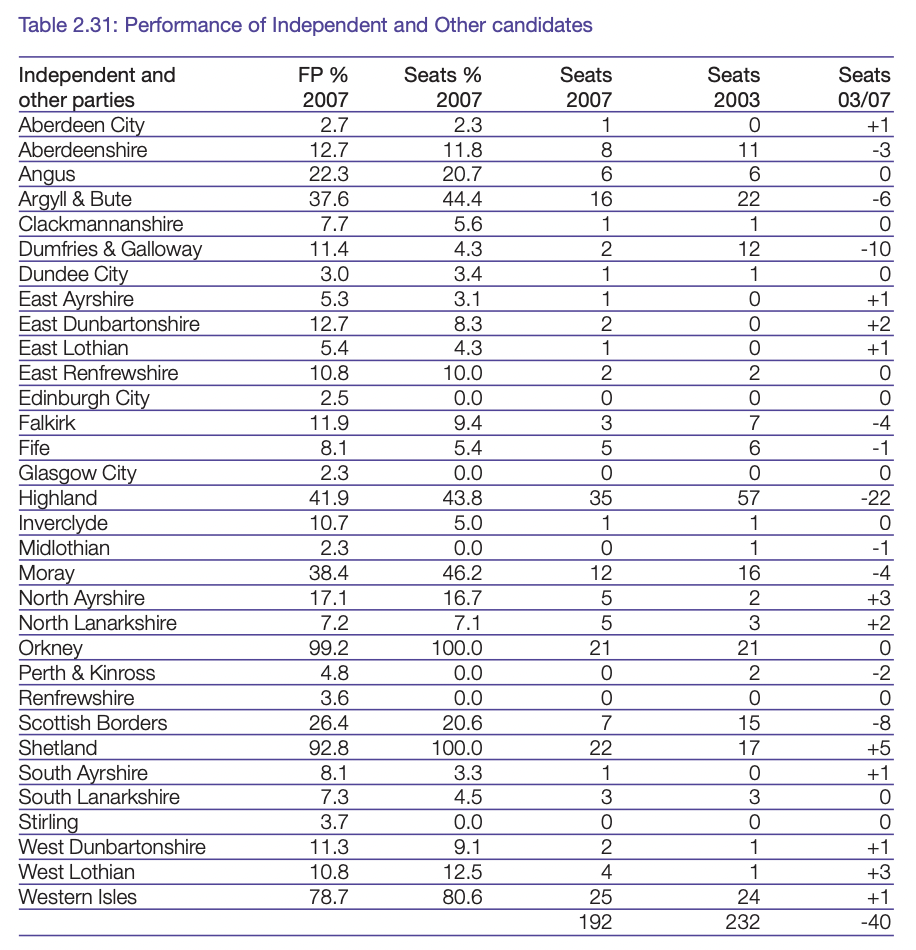

Non-party politics remains an important feature of the electoral landscape in rural Scotland. Table 2.31 summarises the performance of candidates not standing for the parties discussed already in this chapter, including Independents.

Two councils, Orkney and Shetland, no longer have any party political councillors, and another, Western Isles, is predominantly Independent. In another council, Highland, Independents are the largest single group but are no longer the dominant force they were before 2007. Moray is an unusual case in which Independents have recovered ground from the political parties since the first elections in 1995; although they are the biggest group on the council there is party competition in local elections.

In Dumfries & Galloway and Perth & Kinross Independents have largely been replaced by party politics, and there are signs that the same process is taking place in Aberdeenshire.

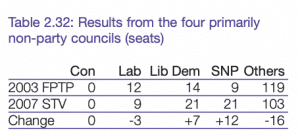

Overall, the STV election in 2007 continued a gradual process of attrition of the oldfashioned rural Independent which had been under way for some time. The move to multimember wards accelerated the pace of change in Highland as the political parties offered voters the option of choosing candidates with a party label and many Independents chose to step down in advance of the election. But the election also showed that the process is not inexorable, as results in Shetland and the Western Isles showed that there is some vitality in the traditional Independent model. Fears raised in advance of the election that STV would see the demise of Independent councils and councillors proved inaccurate. Taking the four councils with a primarily non-party mode of politics (thus impossible to model for what an STV result would have looked like in 2003), the change between the two elections even from FPTP to STV was relatively minor overall. However, this did mask considerable change in Highland, where the Liberal Democrats and the SNP leapt forward.

However, the traditional Independents are not the only model. Some Independents are strongly left wing, like the councillors elected in working-class Fife villages. Some again are disgruntled former members of political parties, whose personal popularity is enough to win them re-election – there are examples of this in East Renfrewshire and East Dunbartonshire.

In the 2007 election still another sort of candidate came forward, representing specifically local interests. The leading examples were Action to Save St John’s Hospital, which won three seats in West Lothian and helped the SNP into power, and the Borders Party whose two councillors make up a vocal opposition force in this rural council. Less successful was the East Kilbride Alliance. While these parties can arise under FPTP, as they have in England in places such as Wyre Forest and Castle Point, the 2007 STV election saw a definite trend in the hitherto party-dominated councils of Ayrshire and Dunbartonshire towards local and independent candidates. Just as the rise of the parties in Highland gave voters more choice, which many of them embraced, so has the challenge to the party dominance of urban Scotland that Independents in all shapes and sized present.

Chapter 3: Candidate strategy in multi-member wards

STV, unlike single-member FPTP, involves a political party making decisions about how many candidates to put up in each ward.

This calculation involves a number of factors, including the basic political sympathies of the ward, the personal reputations of the candidates, balancing a ticket by locality, sex or ethnicity, and the prevailing political climate in the country as a whole and in the particular local authority.

In the context of 2007, nominating more than one candidate was most associated with the Labour Party. Labour was traditionally the strongest party in Scotland, and also has particularly strong concentrations of support in urban central Scotland, while its main competitor, the SNP, has more evenly distributed support. Labour could therefore anticipate electing more teams of candidates than the other parties. Labour also came into the 2007 elections knowing that its inflated total of seats under FPTP was bound to be reduced, but with difficult decisions about sacrificing incumbents and allowing some new talent to come forward.

Multiple nominations and campaigning

More than half of the wards in Scotland (51 per cent) had more than one Labour candidate, compared to only 12.1 per cent of wards with more than one Conservative, 16.1 per cent with more than one Liberal Democrat and 27.2 per cent with more than one SNP candidate

Looked at another way, 76.3 per cent of Labour candidates were part of a ‘team’ with other candidates in the same wards, compared to only 45.2 per cent of SNP candidates and even fewer for the other parties. Labour candidates accounted for nearly half of the total number of candidates who were part of a slate of more than one.

Labour therefore has the most experience coming out of the 2007 elections of the campaigning and management issues involved with running teams of candidates, and of instructing the voters about how to use several preferences to best effect. It is this political context which makes some of the questions that have arisen about ballot order so politically contentious. A ballot structure that assists a party in campaigning as a unit and highlights cases of multiple nomination may therefore be seen as particularly favouring Labour. Likewise, a ballot structure that disperses candidates from the same party around the paper, or makes it difficult for a party to indicate to its supporters how they could vote to help the party best, would be seen as particularly undermining Labour. The context of the next election may be different, in that there may be more multiple SNP candidates in urban central Scotland, but it is a consideration that is very likely to maintain a partisan tinge.

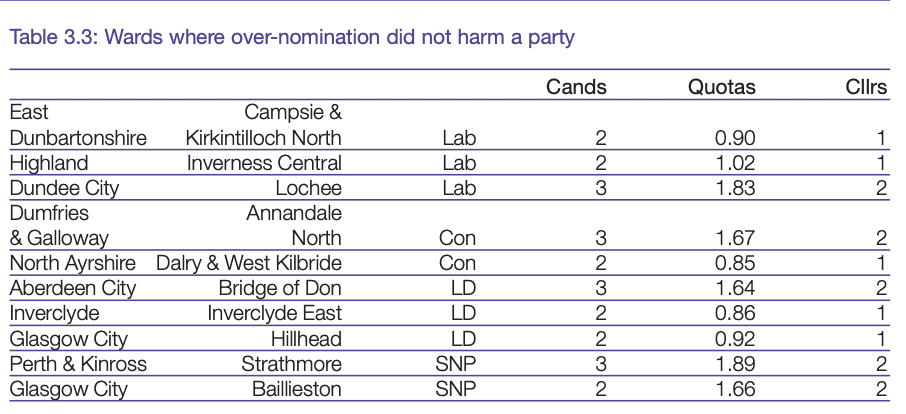

Over-nomination

Before the elections, party managers were often concerned about the risks of nominating too many candidates in a ward. If votes transferred completely along party lines, the party could not lose out from nominating more candidates than it could hope to elect, as is the case under STV in Malta. However, it is a consideration in Ireland because voters there do not stay within party lines and votes ‘leak’ away from the party whenever one of its candidate’s votes is transferred. In Scotland, the parties did not know how many voters would stick with them throughout their slate of candidates, and had little evidence to guide them because it was the first STV election since the 1920s. The boundaries were entirely different, making the parties reliant on guesswork about where their support might be.

Another worry was that party supporters would fail to transfer their votes effectively because they were unfamiliar with STV and might vote only for one candidate or, even worse, invalidate their ballot by trying to vote with multiple X votes. It was understandable that some took a cautious approach to nominations. The SNP in particular tended to aim low, sometimes putting up only candidates who were more or less certain to get in and not going for an ambitious seatmaximising strategy. An additional factor with the SNP was caution, having had hopes of good results dashed in several past elections, about whether their strong polling position during the campaign would last through to polling day.