Introduction

An unusual election

The 2010 election saw a number of unique and interesting features of the campaign and the result.

Leader debates

The 2010 campaign was the first to feature direct, head-to-head televised debates between the leaders of the three largest UK parties. These debates changed the nature of the campaign and inspired considerable public interest in the campaign.

A hung parliament

The 2010 election was the first since February 1974 to produce no overall majority for any party (although there were hung parliaments in 1976-79 and intermittently in 1994-97 as government majorities were whittled away).

House of Commons majorities have become the norm and indeed this pattern is used as an argument in favour of the FPTP electoral system.

However, the lack of an overall majority for any party among the people who voted is nothing new – there has not been a majority mandate for any party since 1935, with the arguable exception of 1955.

A transfer of power

The election was also relatively unusual in producing a transfer of power. The previous occasion was of course Labour’s win in 1997; but apart from the turbulent 1970s, which produced three switches of power, there have only been two other occasions since the end of the war – 1951 and 1964. Even then, 2010 came tantalisingly close to an outcome where

a reconfiguration of the government as a Labour-led coalition, rather than a full transfer of power, might have been possible: Labour fell a few seats short of this possibility.

While causing a power shift, the 2010 election confirmed another surprising fact about British government – that the classical picture of

a majority government of one party cleanly replacing a majority of the other main party (the basis of the argument that FPTP enables voters to kick out a government) is a rare event. Since the mass franchise in 1885, there has only been one such occasion – Edward Heath’s singular victory in 1970. All others, without exception, have involved coalitions, minority government or parliaments with too narrow a majority to allow government for a full term.

Transfers of power in British government

| Year |

Outgoing government |

Incoming government |

| 1905* |

Conservative |

Working majority |

Liberal |

Minority |

| 1915* |

Liberal |

Minority |

Lib-Con-Lab |

Coalition |

| 1922* |

Nat-Lib-Con |

Coalition |

Conservative |

Working majority |

| 1924* |

Conservative |

Minority |

Labour |

Minority |

| 1924 |

Labour |

Minority |

Conservative |

Working majority |

| 1929 |

Conservative |

Working majority |

Labour |

Minority |

| 1931* |

Labour |

Minority |

Con-Lib-Nat Lab |

Coalition |

| 1940* |

Conservative |

Working majority |

Con-Lab-Lib |

Coalition |

| 1945 |

Coalition/ caretaker |

Coalition |

Labour |

Working majority |

| 1951 |

Labour |

Inadequate majority |

Conservative |

Working majority |

| 1964 |

Conservative |

Working majority |

Labour |

Inadequate majority |

| 1970 |

Labour |

Working majority |

Conservative |

Working majority |

| 1974 |

Conservative |

Working majority |

Labour |

Minority |

| 1979 |

Labour |

Minority |

Conservative |

Working majority |

| 1997 |

Conservative |

Minority |

Labour |

Working majority |

| 2010 |

Labour |

Working majority |

Con-LD |

Coalition |

* Transfer of power took place with out an election. Elections followed shortly afterwards in 1905-1906, 1922 and 1931 which ratified the new governments. The first transfer in 1924 followed a liottle after an election; arguably 1974 and 2010 when incumbent governments stayed on for a few days, are comparable.

Coalition government

The general election of 6 May 2010 was a remarkable enough campaign and result, even without the dramatic political developments of the following week in which the Conservative- Lib Dem coalition was agreed – Britain’s first coalition formed outside wartime or emergency since 1918, or arguably even 1895. By comparison with other nations, even those quite experienced in coalition government,

the inter-party discussions were orderly and took place relatively rapidly, enabling the agreement of a coalition programme and formation of a government the week after the general election. There was no financial crisis (even given the unstable conditions in world markets) and few in either coalition party feel that they have traded away their manifesto commitments in the proverbial (and largely mythical) smoke-filled room – most of the policies of the government reflect those of the larger party in the coalition, namely the Conservatives. Many of the spectres conjured up about hung parliaments and coalitions have turned out to be entirely illusory; Britain’s political leaders proved capable of dealing with the new situation.

The possibility of reform

The 2010 election also involved the serious prospect of a change to the electoral system for the House of Commons. The outgoing Labour government’s manifesto promised a referendum on the Alternative Vote (AV). The two incoming coalition parties had different policies (the Lib Dems for proportional representation, the Conservatives for FPTP) but compromised on a referendum on AV

as well.

The election results

2010 results

| Party |

Votes |

Votes % |

Change on 2005 % |

Seats |

Seast % |

Change on 2005 |

| Conservative |

10,698,394 |

36 |

3.8 |

306 |

47.1 |

97 |

| Labour |

8,609,527 |

29 |

-6.2 |

258 |

39.7 |

-91 |

| Lib Dem |

6,836,824 |

23 |

1 |

57 |

8.8 |

-5 |

| UKIP |

919,546 |

3.1 |

0.9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| BNP |

564,331 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| SNP |

491,386 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

6 |

0.9 |

0 |

| Green |

285,616 |

1 |

-0.1 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

| Sinn Fein |

171,942 |

0.6 |

-0.1 |

5 |

0.8 |

0 |

| DUP |

168,216 |

0.6 |

-0.3 |

8 |

1.2 |

-1 |

| Plaid Cymru |

165,394 |

0.6 |

-0.1 |

3 |

0.5 |

1 |

| SDLP |

110,970 |

0.4 |

-0.1 |

3 |

0.5 |

0 |

| UCUNF |

102,361 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

| APNI |

42,762 |

0.1 |

0 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

In contrast to 2005, the electoral system did not produce a House of Commons majority for a party whose support lay in the mid-30 per cent range; the Conservatives fell short in 2010 while Labour, with a slightly lower share of the UK vote, managed to win a comfortable majority in 2005. However, the share of seats for both the Conservatives and Labour was markedly higher than the parties’ share of the popular vote – 57 per cent of the vote between them produced 89 per cent of the seats. As in election after election, the Liberal Democrats’ share of seats was much lower than their share of the vote, and in 2010 they suffered a perverse result of their national share of the vote going up a bit and their number of seats going down. Among the smaller parties, UKIP was easily the largest, with nearly a million votes, but it did not even come close to gaining representation in the House of Commons. In contrast, smaller parties with concentrated support such as the Democratic Unionist Party, Sinn Fein and Plaid Cymru managed to get similar shares of seats to votes, and the Greens broke through by exploiting the ability of FPTP to reward targeted campaigning and concentrated votes and win in Brighton Pavilion.

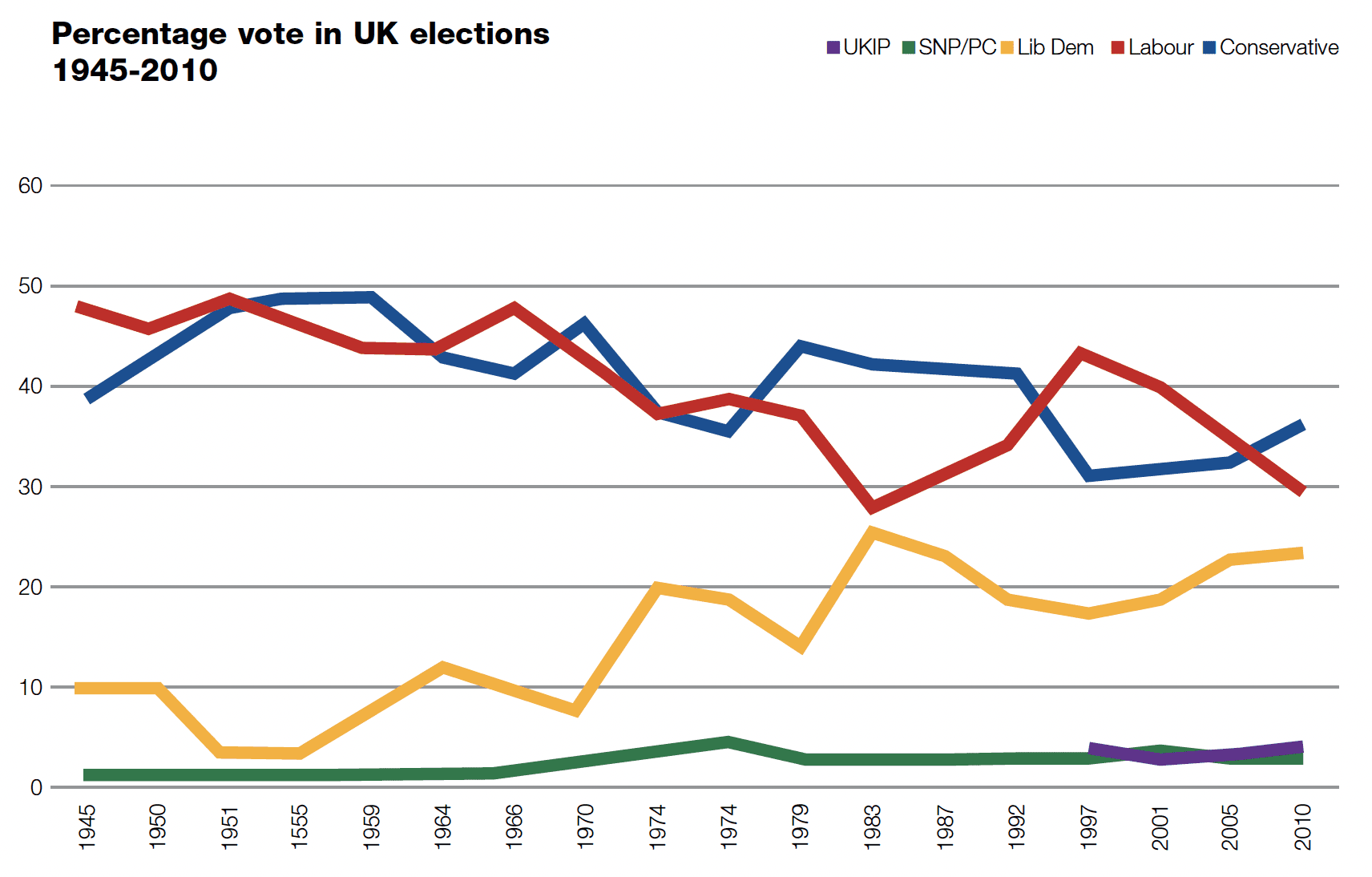

Percentage vote in UK elections 1945-2010

Looking at the longer-term trends, it is clear that in terms of the popular votes cast, the 2010 election resembles 2005 more closely than either election resembles anything previously. There was a strongly rooted two party system from 1945 (actually back to 1931) to 1974, in which Conservative and Labour could command solid blocs of support in the electorate, but since 1974 no party has managed more than the 43.9 per cent support won by the Conservatives in 1979. First Labour, then the Conservatives, and now Labour again, have plunged to historically low levels of support in general elections (and suffered even wilder fluctuations in mid-term elections). Support for the Liberals and Liberal Democrats has tended to rise, although the pattern seems to be for it to come in sharp jumps (1964, 1974, 1983) followed by gradual declines. For a time during the campaign, 2010 looked as if it would see a fourth sharp spike in Lib Dem support, up to 30 per cent or thereabouts, but it was not to be.

Seats won in UK Parliamentary elections, 1974-2010

In terms of seats, the composition of the House of Commons reflected (if rather exaggerated) the two-party voting patterns of Britain from 1945 until 1974, but since then the rise in representation for third and fourth parties has not kept pace with the rise in their support among the electorate. It took until 1997 for the proportion of MPs unaffiliated to the Conservatives or Labour to climb above 10 per cent (for the first time since 1929) and there has been no great breakthrough despite the very low shares won by Conservative and Labour in 2005 and 2010.

Votes per MP, 2010

An easy way of demonstrating uneven results for the parties in the election is to divide each party’s total vote by the number of MPs it obtained.

Three parties with significant levels of support failed to obtain any seats for their votes, namely UKIP, BNP and UCUNF.

Turnout

Turnout in the 2010 general election was 65.1 per cent.

This was a modest increase on the very low- level turnout reached in the two previous elections, when it was only around 60 per cent. It was still well below the electoral participation that used to be regarded as normal – in no previous election since 1918 had turnout fallen below 70 per cent.

Over the long term, there are several well- established factors that influence turnout. One is administrative – how accurate the register may be, and the number of people who are on the register despite having moved away or died. The key political variables are how competitive the voters perceive an election to be, and how important they feel the difference between the parties to be. Turnout in elections like 2001, when the result is perceived as a foregone conclusion and the differences as not very important, is low, while it is high in elections like 1992 when the election is seen as close and the result as being important. The context in 2010 seemed more uncertain than in most elections (since 1979, only 1992 has been comparable), and passions among the parties’ supporters seemed slightly stronger than they had in other recent elections.

However, there does also seem to have been a steady decline in turnout over time, reflecting weakening attachment by electors to political parties and to the political process in general. The drop in 2001 apparently reflected a sudden change of attitude by people who were not particularly interested in politics, and now decided that they did not feel much obligation to vote. It is lowest among young people and among some, but by no means all, ethnic minority communities. That it is so low among young people is worrying, because unless they are socialised into voting at some point, turnout will continue to drop.

Turnout in 2010 appears to have been higher among men than women, although this is an unusual pattern (there is normally little difference). Ever since the late 1980s turnout has tended to be higher among the middle class, homeowners and the more educated, and this was the pattern again in 2010 according to the best available estimates.

Turnout at constituency level is influenced mostly by the demographics of the seat. This is one of the reasons for the pro-Labour bias in the electoral system, in which for a given share of the vote, Labour will win more seats than the Conservatives. Safe Conservative seats tend to have concentrations of high turnout groups like the upper middle class and older people, so the party piles up large numbers of surplus votes that swell MPs’ majorities. Safe Labour seats in city areas, with younger and poorer populations, have lower turnout and therefore the party wastes fewer votes.

Turnout in several categories of seat

Turnout is also influenced by political competitiveness – marginal seats tend to produce higher turnout.

There may be some direct effect, in that some people know that their seat is safe and they do not vote because they know that it would make no difference.

But it is likely that the main mechanism is through the parties. Campaign activity (leafleting, phone canvassing, knocking on doors) is more intense in marginals, and this makes more voters aware of the election and encourages them to feel they have a stake in the process.

It does appear that marginality is worth a couple of extra points on turnout, but a more precise finding has to await statistical analysis so that the effects of marginality and demographics can be separated out. The contrast between the 100 safest Conservative seats, whose turnout is above average and higher than that in marginals, and the 100 safest Labour seats, where turnout is particularly low, suggests that the effect of demographics is much stronger than that of marginality.

By international comparison, Britain’s electoral participation in 2010 was fairly low. The table on Page 11 shows turnout in the latest election in the 27 European Union countries, plus a few others with parliamentary systems.

Most of the EU states with turnout lower than Britain are former communist states in eastern and central Europe, where civic participation is low in general. In general, countries with proportional voting systems have higher turnout than those with single seat majoritarian systems.

Britain’s lack of democratic enthusiasm remains a problem; the fact that fewer than two electors in three cast votes in the most competitive election since 1992 indicates that alienation from the electoral process has certainly not gone away.

Turnout in recent general elections in EU and other states

| Rank (EU) |

Country |

Last election |

Turnout % |

Electoral system |

| 1 |

Malta |

Mar-08 |

93.3 |

STV+ |

| 2 |

Belgium |

Jun-07 |

91.1 |

(CV) Semi open list |

| 3 |

Luxembourg |

Jun-09 |

90.9 |

(CV) Open list |

| 4 |

Cyprus |

May-06 |

89 |

Semi open list |

| 5 |

Denmark |

Nov-07 |

86.6 |

Tiered open list |

| 6 |

Sweden |

Sep-06 |

82 |

Semi open list |

| 7 |

Austria |

Oct-08 |

81.7 |

Semi open list |

| 8 |

Italy |

Apr-08 |

80.4 |

Majoritarian closed list |

|

New Zealand |

Nov-08 |

79.5 |

MMP |

|

South Africa |

Apr-09 |

77.3 |

Closed list |

|

Norway |

Sep-09 |

76.4 |

Semi open list |

| 9 |

Spain |

Mar-08 |

76 |

Closed local list |

| 10 |

Netherlands |

Jun-10 |

75.4 |

Semi open list |

| 11 |

Greece |

Oct-09 |

70.9 |

Majoritarian open list |

| 12 |

Germany |

Sep-09 |

70.8 |

MMP |

|

Japan |

Aug-09 |

69.3 |

MMM |

| 13 |

Ireland |

May-07 |

67 |

STV |

|

Israel |

Feb-09 |

65.2 |

Closed national list |

| 14 |

United Kingdom |

May-10 |

65.1 |

FPTP |

| 15 |

Finland |

Mar-07 |

65 |

Open list |

| 16 |

Hungary |

Apr-10 |

64.4 |

Tiered lists/two-round |

| 17 |

Slovenia |

Sep-08 |

63.1 |

Semi open list |

| 18 |

Czech Republic |

May-10 |

62.6 |

Semi open list |

|

Iraq |

Mar-10 |

62.5 |

Open list |

| 19 |

Estonia |

Mar-07 |

61.9 |

Semi open list |

| 20 |

Latvia |

Oct-06 |

61 |

Semi open list |

| 21 |

Bulgaria |

Jul-09 |

60.9 |

MMP |

|

Jamaica |

Sep-07 |

60.4 |

FPTP |

| 22 |

France |

Jun-07 |

60 |

Two-round |

| 23 |

Portugal |

Oct-09 |

59.7 |

Closed list |

|

India |

Apr/May 09 |

59.7 |

FPTP |

|

Canada |

Oct-08 |

58.8 |

FPTP |

| 24 |

Slovakia |

Jun-06 |

54.7 |

Semi open list |

| 25 |

Poland |

Oct-07 |

53.9 |

Closed local list |

| 26 |

Lithuania |

Oct-08 |

48.6 |

MMM |

| 27 |

Romania |

Nov-08 |

39.2 |

MMP |

(CV: compulsory voting; STV+: STV with national seat adjustment; MMP: Mixed Member Proportional; MMM: Mixed Member Majoritarian

The 2010 election in the nations of the UK

England

| Party |

Votes |

Votes % |

Change on 2005 % |

Seats |

Seats % |

Change on 2005 |

| Conservative |

9,908,169 |

39.6 |

3.9 |

297 |

56.1 |

91 |

| Labour |

7,042,398 |

28.1 |

-7.4 |

191 |

36.1 |

-87 |

| Lib Dem |

6,076,189 |

24.2 |

1.3 |

43 |

8.1 |

-4 |

| UKIP |

866,633 |

3.5 |

0.9 |

0 |

– |

– |

| BNP |

532,333 |

2.1 |

1.3 |

0 |

– |

– |

| Green |

258,954 |

1 |

-0.1 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

| Speaker |

22,860 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

| Respect |

33,251 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

0 |

– |

-1 |

| Ind KHHC |

16,150 |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

– |

-1 |

In one sense, the Conservatives won the election decisively in England, with a vote share more than 11 points ahead of Labour and a clear majority of parliamentary seats. This contrasted with the anomalous result in England in 2005, when the Conservatives had a very narrow lead in vote share but Labour won an overall majority of seats. However, even in 2010 the Conservative vote share was still under 40 per cent, well below what it was in the 1979-97 period and comparable to their losing performances in 1974.

For Labour, there was not a great deal to celebrate in the English results; the party polled its lowest vote share since 1918, with the exception of 1983. At least the party did not come as close as it did in 1983 to coming third in votes in England. It was the second-best Liberal year in England since 1923 (after, again, 1983) in terms of share of the vote, although the haul in seats disappointed the party.

It is worth noting that while Scottish and Welsh politics were revolutionised by the rise of nationalism in the 1970s, there was no comparable change in England where a

three party system remained firmly established through to the last decade. The UKIP vote in 2010 showed that there is a base of support

(small, as yet, in general elections) for the party. It polled a higher share in 2010 than the combined share of UKIP and the Referendum Party in 1997, when the political context was more favourable (Europe high on the public agenda, many Conservatives dissatisfied

with a tired government, and Sir James Goldsmith’s millions spent on the campaign). The low-end results for both Labour and Conservative, and the emergence of significant fourth parties (UKIP in votes, the Greens in winning a seat), suggest that the long-term future is for multi-party politics beyond the big three in England as well.

In terms of seats, both the Conservatives and Labour won much larger shares than they did in votes, with the Conservatives translating 40 per cent of the vote into 56 per cent of the seats. The Liberal Democrats were the principal losers in terms of seats, with a little less than a quarter of the vote producing a twelfth of the seats available.

Seats won by party in England 1974-2010

Votes share in England, 1974 - 2010

Scotland

| Party |

Votes |

Votes % |

Change on 2005 % |

Seats |

Seats % |

Change on 2005 |

| Labour |

1,035,528 |

42 |

3.1 |

41 |

69.5 |

1 |

| SNP |

491,386 |

19.9 |

2.3 |

6 |

10.2 |

– |

| Lib Dem |

465,471 |

18.9 |

-3.7 |

11 |

18.6 |

– |

| Conservative |

412,855 |

16.7 |

0.9 |

1 |

1.7 |

– |

| UKIP |

17,223 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

|

|

|

| Green |

16,827 |

0.7 |

-0.3 |

|

|

|

| (Speaker) |

|

|

|

|

|

-1 |

The 2010 election in Scotland was notable in its complete detachment from the trends in England and Wales. The Scottish Labour Party did not just keep the national swing down, but actually increased its share of the vote. This reflects the traditional commitment of Scotland to centre-left government (and the return of many Labour voters who had withheld their support in 2005), but was also in 2010 a ‘favourite son’ vote for Gordon Brown. The only seats to change hands were a technical transfer of Glasgow North East from Speaker to Labour (which took place at a by-election in 2009) and Labour’s recovery of two by-election losses, Dunfermline & West Fife (2006, Lib Dem) and Glasgow East (2008, SNP).

The Scottish Conservatives were the principal losers from the electoral system, with one vote in six for the party translating into one seat out of 59 (David Mundell’s hold in Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale & Tweeddale). Labour’s represen- tation benefited from a swing in the party’s favour and also being by far the leading political party in Scotland, over 20 points ahead of its nearest rival among Scottish voters, the SNP, and consolidated its position of dominance in Scotland’s representation at Westminster which it has enjoyed since at least 1987.

The strong results for Labour incumbents in several marginal seats means that Labour’s position is perhaps even more formidable than it looks, because few of the party’s MPs are vulnerable to anything except a very large swing. The Conservatives’ target seats of East Renfrewshire and Stirling receded even further, the SNP are further behind in Ochil & South Perthshire, and Labour’s line held in seats threatened by the Lib Dems in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. Itwould only take relatively small further swings to Labour for several more seats to fall to

the party, including East Dunbartonshire, Edinburgh West and Argyll & Bute (all from the Liberal Democrats), Dumfriesshire (from the Conservatives) and Dundee East (from the SNP). Under the FPTP electoral system

there seems little prospect of Labour’s grip on Scottish representation at Westminster being broken even if its vote falls considerably from its relatively high level in 2010.

Even had the Conservatives won a slightly larger swing and formed a majority government, they fell so short in Scotland that they would still have only had one MP north of the border, who would have ended up Scottish Secretary. Such a position would have been awkward to say the least. However, thanks to the Liberal Democrats gaining more or less their proportional share of seats, the governing UK coalition does have some depth of representation in Scotland.

Seats won and share of vote by party 1974-2010

Wales

| Party |

Votes |

Votes % |

Change on 2005 % |

Seats |

Seats % |

Change on 2005 |

| Labour |

531,601 |

36.2 |

-6.5 |

26 |

65 |

-4 |

| Conservative |

382,730 |

26.1 |

4.7 |

8 |

20 |

5 |

| Lib Dem |

295,164 |

20.1 |

1.7 |

3 |

7.5 |

-1 |

| Plaid Cymru |

165,394 |

11.3 |

-1.3 |

3 |

7.5 |

1 |

| UKIP |

35,690 |

2.4 |

1 |

|

|

|

| BNP |

23,088 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

| Green |

6,293 |

0.4 |

-0.1 |

|

|

|

| (Independent) |

|

|

|

|

|

-1 |

Wales, in sharp contrast to Scotland, was a fairly successful area for the Conservatives, with the swing (5.6 per cent) being the same as in England on this occasion. The Tories gained four seats from Labour (Aberconwy; Cardiff North, where Conservative electoral reformer Jonathan Evans narrowly defeated Julie Morgan; Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire; and Vale of Glamorgan) and in the biggest reverse of the election in Wales, former Conservative AM Glyn Davies defeated celebrity Lib Dem, Lembit Opik, in Montgomeryshire. Plaid Cymru also made a notional ‘gain’ from Labour in the radically revised seat of Arfon, and Labour recovered Blaenau Gwent from Independent Dai Davies.

Labour were heavily over-represented in Wales compared to their share of the vote, having

a clear majority (nearly two thirds) on 36 per cent of the vote. The Liberal Democrats were particularly disadvantaged by the electoral system, recording some poor results in seats they held or aspired to gain (with the notable exception of Ceredigion) and having surges in their share of the vote in constituencies such as Pontypridd and Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney unrewarded by seat gains.

Over the longer term, Labour’s vote in Wales reached a historic low in 2010 – lower even than in 1983 – although the Conservatives failed by some way to recapture the sort of vote share that they enjoyed in Wales when they were winning majorities at Westminster in 1979-97.

Share of vote % by party in Wales 1974-2010

Seats won by party in Wales 1974-2010

Northern Ireland

| Party |

Votes |

Votes % |

Change on 2005 % |

Seats |

Seats % |

Change on 2005 |

| Sinn Fein |

171,942 |

25.5 |

1.2 |

5 |

27.8 |

|

| DUP |

168,216 |

25 |

-8.7 |

8 |

44.4 |

-1 |

| SDLP |

110,970 |

16.5 |

-1 |

3 |

16.7 |

|

| UCUNF |

102,361 |

15.2 |

-2.6 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

| Alliance |

42,762 |

6.4 |

2.5 |

1 |

5.6 |

1 |

| Ind U |

42,481 |

6.3 |

|

1 |

5.6 |

1 |

| TUV |

26,300 |

3.6 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

| Green |

3,542 |

0.5 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

Northern Ireland elections are sometimes mirror images of the contest in Great Britain in terms of the level of public interest and

turnover of seats. In 2001, while turnout slumped and there were few changes in Britain, it was a dramatic election in Northern Ireland. In 2010, however, there was a quieter election than the last couple in the province and turnout fell sharply.

The result, though, was notable in some ways. It was the first Westminster election in Northern Ireland in which Sinn Fein was the largest single party (the party also placed first in the European election in 2009). The two main nationalist parties outpolled the combined showing of the two main unionist parties for the first time (42.0 per cent to 40.2 per cent, although Unionist independents and Traditional Unionist Voice polled another 9.9 per cent, taking the combined unionist vote to just over 50 per cent).

Two seats changed hands in Northern Ireland. In one of the most surprising results of the whole night, the Alliance Party candidate, Naomi Long, won Belfast East on a huge swing, unseating the DUP First Minister Peter Robinson. It was the first seat the Alliance had won in a Westminster election, although it had the adherence of an ex-Conservative in the 1970-74 Parliament and polled well on a couple of previous occasions in Belfast East. The other change was a more technical one. Lady Sylvia Hermon had been the Ulster Unionist Party’s sole representative in the previous Parliament, but fought in 2010 as an Independent rather than under the UUP’s joint banner with the Conservatives. She held her North Down seat with a huge majority.

Rather by accident, the proportions of MPs elected from each community were very much in proportion with the votes cast. The Unionist parties, plus the Unionist Independents in Fermanagh & South Tyrone and North Down, won 50.4 per cent of the vote and half the seats; Nationalists won 42.0 per cent of the vote and 44.4 per cent of the seats, and there was one Alliance seat (5.6 per cent of the total) for the 7.6 per cent of those voting for other candidates.

Within the Nationalist community there was also an uncannily proportional result, with the SDLP winning 39 per cent of Nationalist votes and 3 out of 8 seats (37.5 per cent) and Sinn Fein the remainder.

The Unionist MPs, however, are unrepresentative of the votes cast. They consist of 8 DUP MPs and one Independent, while the Ulster Unionist Party/ Conservative alliance had 30 per cent of the Unionist vote but no MPs to show for it.

Vote share % by party in Northern Ireland 1974-2010

Seats won in Northern Ireland by party 1974-2010

A national election?

Swing

Although there were wide variations in swing at the level of individual constituencies, the broad pattern of electoral change in the different parts of Britain was surprisingly uniform, with a few very marked exceptions. There was a national swing of 5 per cent from Labour to Conservative (pretty comparable with past Conservative returns to power in 1970 and 1979), but this consisted of a swing in most of the country of a bit over 6 per cent, from which several areas opted out. Scotland went its own way by swinging in Labour’s favour, Merseyside had no significant swing (which dragged the North West to its below-average 4.3 per cent swing), and London moved by much less than average. The differences between swing in other regions were smaller, although there was a general tendency for the Eastern regions – apparently regardless of class composition and political traditions – to swing a bit more enthusiastically to the Tories.

Taking a longer-term perspective, looking back to the election of 1992 when the gap in vote share between Conservative and Labour was similar to what it was in 2010, gives a clearer picture of the cumulative effect of regional swings. Wales emerges from this analysis as Labour’s worst region (the party’s vote share has fallen by 13.3 percentage points; the

Conservatives’ drop was rather low, 2.5 per cent). Scotland is at the other end of the scale, with Labour actually increasing its support since 1992 and the Conservatives dropping sharply. The other region that has seen a significant shift since 1992 is London, where the Conservative share has dropped most (down 10.8 per cent) and Labour’s support held steady (down only 0.4 per cent). The other regions of England vary less, although there is a distinct east-west pattern to swing, with the eastern side of England (plus the Midlands) trending Conservative and the west (except the West Midlands) to Labour. Perhaps surprisingly, the South East has seen a relative Labour improvement since 1992.

This analysis has concerned the votes cast by the electors, and underpins the general theme of the gradual regional polarisation of politics over the long term – which in turn may be linked to the workings of the electoral system in reflecting the regional differences in an exaggerated form in parliament.

One of the most surprising features about the relationship between votes and seats in 2010 is that nearly one Labour vote in five (19.6 per cent) was cast in the three southern English regions (Eastern, South East, South West) – more than in Scotland and Wales combined. But the composition of Labour’s Parliamentary party is very different – fewer than one Labour MP in twenty represents a seat in southern England outside London. In these regions there are ten Labour MPs (Plymouth Moor View, Exeter, Bristol South, Bristol East, Oxford East, Slough, Southampton Itchen, Southampton Test, Luton North and Luton South) while – with fewer actual Labour voters – Scotland and Wales send 67 Labour representatives. While in elections Labour wins and it does gain representation in the south, these are marginal and vulnerable to setbacks. That Labour’s parliamentary party is so lopsidedly northern, Welsh and Scottish will affect its political approach and policy making, and internal processes like leadership elections.

Swing (%) from Labour to Conservative by region

Distribution of Labour votes and seats (%) by region, 2010

Distribution of Conservative votes and seats (%) by region, 2010(%) by region, 2010

A polarising parliament: votes and seats by region 1992 and 2010

|

Conservative votes % 1992 |

Conservative votes % 2010 |

Conservative seats % 1992 |

Conservative seats % 2010 |

Labour votes % 1992 |

Labour votes % 2010 |

Labour seats % 1992 |

Labour seats % 2010 |

| Southern |

39.5 |

43.7 |

47.9 |

53.1 |

19.5 |

19.6 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

| London |

11.6 |

11 |

14.3 |

9.2 |

11.5 |

14.1 |

12.9 |

14.7 |

| Midlands |

18.1 |

18.3 |

17 |

21 |

18.4 |

17.1 |

15.9 |

15.1 |

| Wales |

3.6 |

3.6 |

1.8 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

6.2 |

10 |

10.1 |

| Northern |

22 |

19.6 |

15.8 |

13.8 |

33.2 |

30.6 |

39.5 |

40.3 |

| Scotland |

5.4 |

3.9 |

3.3 |

0.3 |

9.9 |

12 |

18.1 |

15.9 |

The Conservative Party in parliament is unrepresentative of its voters, in a mirror image of Labour’s distorted representation. Although southern England is its strongest region in votes, this dominance is exaggerated in seats to the extent that a majority of Tory MPs represent seats in southern England.

Northerners and Scots who vote Conservative got relatively little representation compared

to their southern colleagues. The concerns of southern England will be more immediately felt by the party in government than those of the north and Scotland, a potential problem given that the impact of austerity will be uneven across the regions. Conflict between the Conservative and Labour parties will be refracted through this regionally polarised representation.

Comparison with 1992 indicates that the southern regional skew of Conservative votes and MPs has increased, while Labour’s

vote distribution has skewed a bit towards Londoners and Scots, although there is an uncanny similarity between the share of the Labour parliamentary party for each region in 1992 and 2010. It is very much back to the much-discussed ‘Southern Discomfort’ for Labour, while the Conservatives seem to be developing a northern problem (particularly in the big cities) alongside their all too obvious troubles in Scotland.

Local representation

Local representation

One of the features of the combination of FPTP elections and Britain’s social and political geography is that some areas end up being dominated by a single party despite that party having the support of half, or fewer, of those voting. Conversely, it is possible for parties

to win significant shares of the vote without winning parliamentary seats – the prize (if not an MP) in 2010 went to the Surrey Lib Dems whose 28.5 per cent of the vote (much more the party’s national share) went unrepresented. This produces the phenomena of the ‘electoral desert’ and what one might call the ‘one party state’ (although the overtone of dictatorship to this term does not apply).

Some of these deserts and strongholds are persistent and apply to elections with widely different national outcomes (such as the Conservatives in Surrey with the sole exception of 2001, or Labour in Glasgow) and some are more transient or variable. In some counties such as Hertfordshire and Kent, Labour can win considerable numbers of seats in a good year for the party, but these are all marginals, which are lost when the tide turns (as they were in 2010). In others, such as West yorkshire, a good Labour year will wipe out all the Conservatives. A party’s seats in a generally hostile region will often tend to be marginal and vulnerable to swings and to boundary changes.

Electoral ‘deserts’ in England, 2010

| County |

Party |

Vote % |

Votes |

PR seats |

| Surrey |

Liberal Democrat |

28.5 |

166,667 |

3 |

| Greater Manchester SE |

Conservative |

28 |

120,544 |

3 |

| Oxfordshire |

Liberal Democrat |

28 |

92,999 |

2 |

| North yorkshire |

Liberal Democrat |

27.9 |

111,283 |

2 |

| Warwickshire |

Labour |

27.6 |

79,428 |

2 |

| West Sussex |

Liberal Democrat |

27.4 |

114,014 |

2 |

| Northamptonshire |

Labour |

25.7 |

88,535 |

2 |

| Hereford & Worcester |

Liberal Democrat |

25.3 |

100,433 |

2 |

| Berkshire |

Liberal Democrat |

25.2 |

104,133 |

2 |

| Suffolk |

Liberal Democrat |

24.1 |

87,695 |

2 |

| Durham |

Liberal Democrat |

24.1 |

69,838 |

2 |

| Hertfordshire |

Liberal Democrat |

24 |

134,793 |

3 |

| Shropshire |

Liberal Democrat |

23.5 |

56,622 |

1 |

| Leicestershire |

Liberal Democrat |

23.3 |

118,341 |

2 |

| Humberside |

Liberal Democrat |

22.5 |

92,399 |

2 |

| Tyne & Wear |

Liberal Democrat |

21.7 |

106,380 |

3 |

| Derbyshire |

Liberal Democrat |

21.6 |

110,385 |

2 |

| Tyne & Wear |

Conservative |

21.4 |

105,117 |

3 |

| Durham |

Conservative |

21.4 |

62,077 |

1 |

| Suffolk |

Labour |

21.3 |

77,775 |

1 |

| Cheshire |

Liberal Democrat |

21.2 |

109,601 |

2 |

| Kent |

Labour |

21.1 |

174,599 |

4 |

| Gloucestershire |

Labour |

21 |

66,858 |

1 |

| Kent |

Liberal Democrat |

20.9 |

173,176 |

4 |

| Buckinghamshire |

Liberal Democrat |

20.9 |

75,881 |

2 |

| South yorkshire |

Conservative |

20.6 |

121,131 |

3 |

| Warwickshire |

Liberal Democrat |

20.5 |

58,837 |

1 |

| Bedfordshire |

Liberal Democrat |

20.3 |

59,184 |

1 |

| Lincolnshire |

Liberal Democrat |

20.2 |

70,827 |

2 |

| East Sussex |

Labour |

20.1 |

81,571 |

2 |

| South East London |

Liberal Democrat |

19.9 |

95,949 |

2 |

| Lincolnshire |

Labour |

19.4 |

68,043 |

1 |

| Nottinghamshire |

Liberal Democrat |

19.2 |

65,676 |

2 |

| Northamptonshire |

Liberal Democrat |

19.1 |

65,676 |

1 |

| Norfolk |

Labour |

19 |

83,088 |

2 |

| Hertfordshire |

Labour |

19 |

106,478 |

2 |

| Essex |

Labour |

18.6 |

157,134 |

4 |

| Staffordshire |

Liberal Democrat |

18.1 |

97,823 |

2 |

| West London |

Liberal Democrat |

17 |

80,468 |

2 |

| Hereford & Worcester |

Labour |

16.7 |

66,394 |

1 |

| Cambridgeshire |

Labour |

16.2 |

60,983 |

1 |

| Buckinghamshire |

Labour |

15.5 |

56,389 |

1 |

| Wiltshire |

Labour |

15.3 |

52,364 |

1 |

| East London |

Liberal Democrat |

15 |

76,520 |

2 |

| Black Country |

Liberal Democrat |

14.5 |

73,446 |

2 |

| West Sussex |

Labour |

13.1 |

54,453 |

1 |

| Dorset |

Labour |

12.2 |

47,594 |

1 |

| Surrey |

Labour |

9.8 |

57,032 |

1 |

| Cornwall |

Labour |

8.6 |

24,257 |

0 |

| Somerset |

Labour |

7.7 |

22,163 |

0 |

| TOTAL (major party) |

|

17 |

4,252,007 |

|

| Minor parties |

|

8 |

2,009,536 |

|

| Overall total |

|

25 |

6,140,999 |

|

English regions and counties

A striking fact about the 2010 election in England was that nearly one voter in four (25.0 per cent) not only did not succeed in electing an MP of their choice in their constituency, but also did not see an MP of their party elected in their broader locality either. There is a sense that an MP can put their party’s case and represent its voters’ point of view in that general area; for instance, having an MP for Withington enables Liberal Democrats in the rest of Manchester to feel somewhat represented in Parliament (and likewise for Labour in Oxfordshire thanks to their hold on Oxford East). However, voters for all three main English parties in many areas do not have that consolation – and neither does any voter for other candidates, except for Greens in East Sussex and John Bercow’s supporters in Buckingham.

Conservative votes and seats in Metropolitan England, 2010

|

Votes % |

Seats |

Seats % |

| Greater Manchester |

27.3 |

2 |

7.4 |

| Merseyside |

21.1 |

1 |

6.7 |

| South yorkshire |

20.6 |

0 |

0 |

| Tyne & Wear |

21.4 |

0 |

0 |

| West Midlands |

33.5 |

7 |

25.0 |

| West yorkshire |

32.9 |

7 |

31.8 |

There were eight English counties (plus a subsection of Greater Manchester) where a party with more than a quarter of the vote ended up unrepresented in that area. The Liberal Democrats were particularly prone to this effect because their vote was evenly distributed, especially in southern England.

Labour’s largest unrepresented shares of the vote were in areas where the party had held marginals in 2005 but lost them in 2010. In East Sussex, a particularly striking example, Labour went from holding half the seats in the county in 2005 on 25.4 per cent, to nothing in 2010 despite winning 20.1 per cent. Both results demonstrate the lack of relationship between vote share and seats won under FPTP.

The Conservatives gained seats in several areas where they had been unrepresented in 2005 (Cornwall, Cleveland, Merseyside) but were still unrepresented in South yorkshire, Durham and Tyne & Wear, despite respectable shares of the vote. They also picked up a few seats in areas where they had previously been extremely under-represented, such as West yorkshire

and the Black Country, but remained short of representation in the metropolitan counties and great cities of England. Many of the seats they do hold in these areas are marginal and could disappear through boundary changes or be lost on an adverse swing.

Conversely, there are several areas that are completely dominated by one party in terms of parliamentary representation, even though there are substantial votes for other parties. In the circumstances of 2010, several of these were traditionally Conservative counties where Labour toeholds had been knocked off, but the results indicate the volatility of some areas such as Northamptonshire – the Conservatives won all six seats in 1992, a solitary seat in 1997 and 2001, three in 2005, and again everything from the county’s allocation of seven in 2010. The Conservatives’ vote of course did not change nearly as much as the county’s parliamentary representation in this time.

One party counties in England, 2010

| County |

Party |

Vote % |

Seats |

| Surrey |

Conservative |

55.2 |

11 |

| West Sussex |

Conservative |

51.8 |

8 |

| Kent |

Conservative |

50.5 |

17 |

| Hertfordshire |

Conservative |

50.4 |

11 |

| Lincolnshire |

Conservative |

49.8 |

7 |

| Tyne & Wear |

Labour |

48.7 |

12 |

| Northamptonshire |

Conservative |

47.4 |

7 |

| Suffolk |

Conservative |

46.2 |

7 |

| Hereford & Worcester |

Conservative |

45.9 |

8 |

| Warwickshire |

Conservative |

45.7 |

6 |

| Durham |

Labour |

45.3 |

7 |

The regions of Scotland

| Region |

Party |

Vote % |

Votes |

PR seats |

| Central |

SNP |

22.2 |

88,881 |

2 |

| North East |

Conservative |

21.4 |

70,286 |

2 |

| Highlands & Islands |

Labour |

20.3 |

46,933 |

1 |

| Glasgow |

SNP |

17.3 |

39,702 |

1 |

| Mid & Fife |

Conservative |

17.3 |

55,485 |

1 |

| Lothians |

SNP |

17.0 |

61,305 |

1 |

| Highlands & Islands |

Conservative |

16.7 |

38,505 |

1 |

| Lothians |

Conservative |

16.2 |

58,647 |

1 |

| South |

SNP |

15.8 |

52,349 |

1 |

| West |

Conservative |

15.7 |

41,102 |

1 |

| West |

SNP |

15.3 |

40,214 |

1 |

While the Conservatives were most under- represented across Scotland, the SNP probably suffered worst from regional disparities. All six of its MPs were elected from northern Scotland, with all but Dundee East being either rural or having a large rural component. However, the three northern regions from which MPs were elected account for fewer than half of the SNP’s actual voters; the party piled up nearly as many votes in the Central region as in North East but won no MPs from the industrial heartland of urban Scotland. SNP

representation in the Scottish Parliament has always had a much larger urban component because of the proportional electoral system used to elect MSPs.

Labour’s strength in the urban centres was exaggerated by the electoral system, but despite its landslide win across Scotland the party did not win any seats in the Highlands & Islands region, even though it won over 20 per cent. In contrast to England, the Liberal Democrats did relatively well in winning at least a seat across most regions of Scotland, with rural, urban and suburban areas returning Lib Dem MPs.

Although Labour dominated across Scotland, most regions did have at least one non-Labour MP.

One party regions in Scotland, 2010

| Region |

Party |

Vote % |

Seats |

| Central |

Labour |

55.5 |

9 |

| Glasgow |

Labour |

56.2 |

7 |

The regions of Wales

As in England, the Liberal Democrats polled well in several regions of Wales without winning seats, although in general the pattern of representation was a bit more pluralistic (with the exception of the all-Labour region of South Wales West). Plaid Cymru’s vote in the South Wales regions was small but this may reflect tactical voting rather than the true level of the party’s support – it certainly polls much better in these regions in Welsh Assembly elections.

Electoral ‘deserts’ in Wales, 2010

| Region |

Party |

Vote % |

Votes |

PR seats |

| South Wales West |

Conservative |

20.7 |

51,887 |

1 |

| South Wales West |

Liberal Democrat |

20.0 |

50,246 |

1 |

| South Wales East |

Liberal Democrat |

18.7 |

55,492 |

2 |

| North Wales |

Liberal Democrat |

16.1 |

49,840 |

1 |

| South Wales Central |

Plaid Cymru |

7.8 |

24,587 |

0 |

| South Wales East |

Plaid Cymru |

6.4 |

19,056 |

0 |

| South Wales West |

Plaid Cymru |

8.6 |

21,568 |

0 |

One party region in Wales, 2010

| Region |

Party |

Vote % |

Seats |

| South Wales West |

Labour |

44.2 |

7 |

Constituency results

Constituencies

At a constituency level, the 2010 election produced a post-war record number and proportion of MPs elected by a minority of their own voters – 433 out of 650 (66.6 per cent). This was slightly up on the previous record number of minority winners, 426 in the 2005 election. One MP, Labour’s Dennis

Skinner in Bolsover, had precisely 50 per cent of the votes cast; the other 216 had over half the votes cast.

The chart below shows the transformation from the period from 1950 to 2001, in which most MPs had over 50 per cent in most elections, to the current position where the support of a majority of those voting is unusual. The failure of the 2010 election to produce more majority winners shows that the fragmented electoral pattern of 2005 was not an aberration (to some extent the results in 1974 were a deviation from the normal pattern). This has added strength to the argument for the Alternative Vote, which would enable all MPs to have a majority (albeit on a qualified basis because not all would have a majority of the valid first preferences in the constituency).

As well as a large number of minority winners, there were also increasing numbers of MPs elected with relatively small amounts of support from their constituents. While it is arguable that in multi-party politics a candidate with 48 per cent may represent near enough to a majority (or at least that a majority cannot be assembled for a rival candidate) this is much more dubious when the winner’s support is below 40 per cent. There are 111 MPs in the 2010 parliament with less than 40 per cent support from their own voters. This was a sharp increase on 2005, when 55 MPs had this status, and from 2001 when it was a rare event – 26 slipped through then on such a low share (the number was 20 in 1992 and 9 in 1970).

Of the 111 MPs with less than 40 per cent support in 2010, 56 are Labour (up 29 on 2005), 34 Conservative (up 26, all but one of whom are gains since 2005), 10 Lib Dems (up 3) and 11 Others (up 11: 4 SNP, 3 DUP, 2 Plaid, 1 Green, 1 APNI). This pattern was particularly prevalent in Wales, with nearly one seat in three being decided on less than 40 per cent of the vote.

Majority and minority winners, 1950-2010

Winners on less than 40 per cent (by nation) 2010

| Nation |

Number |

% |

| England |

80 |

15 |

| Wales |

13 |

32.5 |

| Scotland |

14 |

23.7 |

| Northern Ireland |

4 |

22.2 |

| UK |

111 |

17.1 |

The general upward trend in the number of MPs with sub-40 per cent vote shares is apparent in the table above, as is the sharp upward movement in 2010. Three factors seem to govern the prevalence of such small minority winners. One is that it is arithmetically impossible to win with less than 50 per cent in a two-way contest, and the last such contests were in 1979 (and they became rare in 1974).

Winning share of the vote in constituency contests, 1950-2010

| General Election |

Below 40% |

40-50% |

Above 50% (2 candidates) |

Above 50% (3+ candidates) |

| 1950 |

8 |

179 |

115* |

323 |

| 1951 |

0 |

39 |

499* |

87 |

| 1955 |

1 |

36 |

489 |

104 |

| 1959 |

0 |

80 |

373 |

177 |

| 1964 |

7 |

225 |

194 |

204 |

| 1966 |

5 |

180 |

234 |

211 |

| 1970 |

9 |

115 |

185 |

321 |

| 1974 Feb |

40 |

368 |

38 |

189 |

| 1974 Oct |

31 |

349 |

0 |

255 |

| 1979 |

13 |

193 |

3 |

426 |

| 1983 |

70 |

266 |

0 |

314 |

| 1987 |

25 |

258 |

0 |

367 |

| 1992 |

20 |

240 |

0 |

391 |

| 1997 |

49 |

264 |

0 |

336 |

| 2001 |

26 |

307 |

0 |

326 |

| 2005 |

55 |

371 |

0 |

220 |

| 2010 |

111 |

322 |

0 |

217 |

Further, the other candidates need to get at least 20 per cent of the vote (meaning that two party politics needs to have weakened).

Another is that boundary changes, by creating new seats where the tactical position is unclear, make for more 30-something (or 20-something) winners, which usually resolves itself in the next election through tactical voting and incumbency (as in 1983-87 and 1997-2001); another is

a strong national movement of votes that encourages people to support their party even when it does not help much in the constituency.

The persistence of Liberalism in rural Wales and Scotland through the party’s UK

nadir, and the rise of Scottish and Welsh nationalism, meant that 30-something winners were formerly to be found mostly outside England (with some constituencies such

as Meirionnydd, Ceredigion, Caithness and

Aberdeen South being repeatedly won with less than 40 per cent). The 2010 election saw winners with less than 40 per cent on an unprecedented scale in England.

Seats won on low shares of the vote in 2010

Simon Wright, the Lib Dem winner in Norwich South, has the wooden spoon for the lowest share of the vote of any MP in Westminster, at 29.4 per cent. This was lower than any MP recorded in 2005, although still more than the recent record holder Sir Russell Johnston, who held Inverness for the Lib Dems in 1992 with 26.0 per cent.

As one might expect, the 21 seats where the winner had 35 per cent or under were mostly three way marginals. There were 9 seats decided on less than 35 per cent of the vote in 2005, so the 2010 election saw a significant increase in the number of MPs with only a small share of constituency support.

Norwich South election result 2010

| Candidate |

Party |

Vote |

Vote % |

| Wright, Simon |

Liberal Democrat |

13,960 |

29.4 |

| Clarke, Charles |

Labour |

13,650 |

28.7 |

| Little, Antony |

Conservative |

10,902 |

22.9 |

| Ramsay, Adrian |

Green |

7,095 |

14.9 |

| Emmens, Steve |

UKIP |

1,145 |

2.4 |

| Heather, Leonard |

BNP |

697 |

1.5 |

| Polley, Gabriel |

Workers Rev Party |

102 |

0.2 |

MPs with 35 per cent or less of the constituency vote, 2010

| MP |

Constituency |

Party |

Vote % |

| Simon Wright |

Norwich South |

Liberal Democrat |

29.4 |

| Caroline Lucas |

Brighton Pavilion |

Green |

31.3 |

| Alan Reid |

Argyll & Bute |

Liberal Democrat |

31.6 |

| Phil Woolas |

Oldham East & Saddleworth |

Labour |

31.9 |

| Austin Mitchell |

Great Grimsby |

Labour |

32.7 |

| Glenda Jackson |

Hampstead & Kilburn |

Labour |

32.8 |

| Roger Godsiff |

Birmingham Hall Green |

Labour |

32.9 |

| Chris Williamson |

Derby North |

Labour |

33.0 |

| Albert Owen |

ynys Mon |

Labour |

33.4 |

| David Ward |

Bradford East |

Liberal Democrat |

33.7 |

| Gloria de Piero |

Ashfield |

Labour |

33.7 |

| David Simpson |

Upper Bann |

DUP |

33.8 |

| William McCrea |

Antrim South |

DUP |

33.9 |

| Michael Ellis |

Northampton North |

Conservative |

34.1 |

| Oliver Colvile |

Plymouth Sutton & Devonport |

Conservative |

34.3 |

| Gregory Campbell |

Londonderry East |

DUP |

34.6 |

| Ian Murray |

Edinburgh South |

Labour |

34.7 |

| Geraint Davies |

Swansea West |

Labour |

34.7 |

| Gavin Shuker |

Luton South |

Labour |

34.9 |

| Richard Harrington |

Watford |

Conservative |

34.9 |

| Simon Reevell |

Dewsbury |

Conservative |

35.0 |

Majority winners (by party) 2010

| Party |

Number |

% (of party) |

% (of majority winners) |

| Conservative |

126 |

41.2 |

58.1 |

| Labour |

76 |

29.5 |

35.0 |

| Lib Dem |

12 |

21.1 |

5.5 |

| Others |

3* |

– |

– |

Majority winners (by nation) 2010

| Nation |

Number |

% |

| England |

185 |

34.7 |

| Wales |

7 |

17.5 |

| Scotland |

22 |

37.3 |

| Northern Ireland |

3 |

16.7 |

Majority winners

Among the total of majority winners, the Conservatives are rather over-represented. The increase in their vote share pushed a number of seats they had won last time with shares of the vote in the high 40 per cent range over into majority winner status. Conversely, Labour’s falling support – particularly in some hitherto safe seats in Wales and south yorkshire – caused a drop in the number of Labour majority winners.

Labour’s strong result in Scotland increased the proportion of majority winners there a little, while the party’s weak showing in the south Wales valleys knocked the number of Welsh majority winners back significantly. Of all the MPs who gained their seat from another party in 2010 relative to 2005, only one – Labour’s Nick Smith who recaptured Blaenau Gwent from Independent – polled over 50 per cent of the vote (a handful of others reversed defections or by-elections, or won a seat where boundary changes had already changed its partisan allegiance).

The preponderance of the very safest seats is for Labour, with Merseyside and urban Scotland providing many of the most rock- solid constituencies.

Share of the electorate

In terms of the share of the entire electorate voting for the successful candidate, no MP can claim a majority after the 2010 election (there were no majorities of electors in 2005 or 2001 either). The general increase in turnout in 2010 and the increase in the Conservative share of the vote meant that rather more MPs had over 40 per cent than in 2005 – 35 seats as opposed to 3 in 2005. Many of these were in rural seats, which are safely Conservative, although there is a slight tendency for a high winning share of the electorate to be associated with a serious Lib Dem challenge a few years ago but which is now fading – as in Orpington, Maidenhead and Surrey South West. Of the 35 MPs who can claim the support of 40 per cent or more of the electorate, three are Lib Dems (Westmorland & Lonsdale, Norfolk North, Bath), one Labour (Gordon Brown in Kirkcaldy & Cowdenbeath) and the other 31 are Conservatives (including David Cameron in Witney).

The 2010 election saw a lot of very individual constituency-level results and the greater deviation from average results is apparent in the fact that as well as more MPs receiving particularly strong support, there was a rise in the number of MPs with particularly weak local support. Eight MPs, compared to three in 2005, received less than 20 per cent support from their electorates.

The fall in turnout in Northern Ireland, and the erosion of the DUP’s dominance since 2005, caused several Northern Ireland seats to appear in this category, and Labour’s good results in Scotland raised the overall level of support for its MPs (two of the three winners with less than 20 per cent of the electorate in 2005 were in Scottish Labour seats). It is perhaps ironic that two of Labour’s most convinced and tenacious electoral reformers, Austin Mitchell and Alan Johnson, should find themselves in this category.

MPs with over 60 per cent of the vote, 2010

| MP |

Constituency |

Party |

Vote % |

| Steve Rotheram |

Liverpool Walton |

Labour |

72.0 |

| Gerry Adams |

Belfast West |

Sinn Fein |

71.1 |

| George Howarth |

Knowsley |

Labour |

70.9 |

| Stephen Timms |

East Ham |

Labour |

70.4 |

| Willie Bain |

Glasgow North East |

Labour |

68.3 |

| Tom Clarke |

Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill |

Labour |

66.6 |

| Joe Benton |

Bootle |

Labour |

66.4 |

| Gordon Brown |

Kirkcaldy & Cowdenbeath |

Labour |

64.5 |

| Stephen Twigg |

Liverpool West Derby |

Labour |

64.1 |

| Sylvia Hermon |

North Down |

Independent |

63.3 |

| William Hague |

Richmond (yorks) |

Conservative |

62.8 |

| Lyn Brown |

West Ham |

Labour |

62.7 |

| Frank Field |

Birkenhead |

Labour |

62.5 |

| Ian Davidson |

Glasgow South West |

Labour |

62.5 |

| Lindsay Roy |

Glenrothes |

Labour |

62.3 |

| Alistair Carmichael |

Orkney & Shetland |

Liberal Democrat |

62.0 |

| Margaret Curran |

Glasgow East |

Labour |

61.6 |

| Gemma Doyle |

Dunbartonshire West |

Labour |

61.3 |

| Dominic Grieve |

Beaconsfield |

Conservative |

61.1 |

| Frank Roy |

Motherwell & Wishaw |

Labour |

61.1 |

| Tom Watson |

West Bromwich East |

Labour |

61.0 |

| Tom Greatrex |

Rutherglen & Hamilton West |

Labour |

60.8 |

| Adam Afriyie |

Windsor |

Conservative |

60.8 |

| James Arbuthnot |

Hampshire North East |

Conservative |

60.6 |

| Greg Hands |

Chelsea & Fulham |

Conservative |

60.5 |

| Cheryl Gillan |

Chesham & Amersham |

Conservative |

60.4 |

| Tim Farron |

Westmorland & Lonsdale |

Liberal Democrat |

60.0 |

MPs with support of more than 43 per cent of the electorate, 2010

| MP |

Constituency |

Party |

Electorate % |

| Tim Farron |

Westmorland & Lonsdale |

Liberal Democrat |

45.5 |

| Cheryl Gillan |

Chesham & Amersham |

Conservative |

45.0 |

| James Arbuthnot |

Hampshire North East |

Conservative |

44.4 |

| Theresa May |

Maidenhead |

Conservative |

43.8 |

| Jeremy Wright |

Kenilworth & Southam |

Conservative |

43.5 |

| Adam Afriyie |

Windsor |

Conservative |

43.4 |

| Paul Beresford |

Mole Valley |

Conservative |

43.1 |

| Jo Johnson |

Orpington |

Conservative |

43.1 |

| Jeremy Hunt |

Surrey South West |

Conservative |

43.1 |

| David Cameron |

Witney |

Conservative |

43.1 |

MPs with support of less than 20 per cent of the electorate, 2010

| MP |

Constituency |

Party |

Electorate % |

| Austin Mitchell |

Great Grimsby |

Labour |

17.6 |

| Jackie Doyle-Price |

Thurrock |

Conservative |

18.3 |

| William McCrea |

Antrim South |

DUP |

18.3 |

| David Simpson |

Upper Bann |

DUP |

18.7 |

| Simon Wright |

Norwich South |

Liberal Democrat |

19.0 |

| Gregory Campbell |

Londonderry East |

DUP |

19.1 |

| Alan Johnson |

Hull West & Hessle |

Labour |

19.4 |

| Phil Woolas |

Oldham East & Saddleworth |

Labour |

19.5 |

Conclusion

The link between constituency and MP, often cited by supporters of the current system as a benefit of FPTP, has clearly changed, not just since the high point of the two party system in the 1950s, but also since the 1990s. The normal pattern is now for two MPs out of every three to lack the support of a majority of local voters, and an increasing number not to reach 40 per cent support. No MP returned in any of the last three elections has had the support of a majority of the local electorate.

The debate over the possibility of moving to the Alternative Vote (AV) was fuelled by the low proportion of MPs with a majority mandate in the 2005 parliament, and this factor has grown rather than receded as a result of the election of 2010.

‘Wasted’ votes in 2010

Wasted Votes

In any electoral system, there are a certain number of votes that do not contribute to electing a member of parliament – even in highly proportional list systems a few votes will be cast for minority lists that do not gain any representation. These are ‘wasted’ in the sense that they do not affect the outcome in terms of seats. In nearly every circumstance there will also be some votes that are given to candidates who end up not needing them – that are surplus to the requirement of getting elected. These votes, too, in a sense, are ‘wasted’ by the system.

In the 2010 election, over half of those who voted failed to elect their chosen candidate and their vote therefore did not contribute to sending anyone to Parliament. The FPTP electoral system is based on the principle of localised winner takes all and there

is no compensation for the voter whose constituency vote was not cast for the successful candidate. In addition, many seats are safe in the sense that one party or other has a large and reliable majority. In these seats, even those who vote for the winner may be dissatisfied with the power that they have exercised, because giving someone a majority of 10,001 rather than 10,000 may feel less of a contribution than securing a win in a closely-contested election. In terms of actually affecting who sits in Parliament, therefore, many votes are ‘wasted’.

The notion of a ‘wasted’ vote is one that needs some clarification. The term seems to carry an unfortunate, and unintended, negative connotation about the voter’s choice, while in fact it is just mechanically descriptive of the way the vote is processed by the electoral system.

- No vote is really ‘wasted’ if that vote serves as a statement of what the voter believes – her support for a party, a person, a policy – or just a statement of belonging to a democratic community.

- ‘Wasted’ votes count towards national and sub-national vote shares. Although these

are not recognised by the electoral system, they play some part in political discourse. For instance, a Conservative vote cast in Liverpool in 2005 was wasted in the normal sense, but it also contributed to the narrow margin by which the Conservatives won the most votes in England and therefore to strengthening the party’s position.

- Votes that are ‘wasted’ in one election can be consequential in the next; votes cast for losing candidates can create momentum

that is reflected in the strategic choices of the parties, the views of voters and the result in the next election. A Liberal Democrat voter in Burnley in 2005 did not see his support elect an MP that time, but that vote helped establish the party as the clear competitor for the next election and thereby the environment that produced a Lib Dem gain in 2010.

- The position is a bit different in marginals and safe seats – in a safe seat, the voter can tell pretty well ex ante whether her choice will be to support a losing candidate or add to a winning candidate’s surplus. In marginals, the vote might turn out to be ‘wasted’ (for a loser), to form a part of a relatively small winner’s surplus, or perhaps even to be the decisive margin of victory. Voting for a potential winner in a marginal is therefore a bit like buying insurance – it is not wasted, even if the policy does not pay off on that occasion.

Votes in 2010 election

So, with these reservations about the term ‘wasted vote’, how many votes in the 2010 general election were either for losing

candidates (and therefore not translated into seats) or were surplus to those necessary to ensure a candidate was elected?

The majority of votes, 52.8 per cent, were cast for losing candidates and therefore did not contribute to electing MPs. Taking votes that ended up being surplus to winners’ requirements, the proportion of votes wasted or partially wasted by the system was 71.1 per cent.

This share is not unusual for the First Past the Post system as it operates in a multi-party context. In 2005 the corresponding shares of the vote were very similar, with 52.4 per cent of votes cast for losing candidates, 29.3 per cent being necessary for winners, and 18.3 per cent forming surpluses for winners.

Votes cast for losing candidates have been consistently more or less 50 per cent since February 1974, although the 2010 share is the highest in recent years.

The proportion of votes cast for losing candidates, or being surplus to winners’ requirements, is much higher under FPTP than in most other electoral systems.

Share of vote for losing candidates 1974-2010

Gender and ethnic representation

Women: House of Commons

The overall number of women in the House of Commons after the 2010 general election rose to another historic high of 143 out of 650 seats. Since the election, the result of the Oldham East & Saddleworth by-election has nudged the figure up to 144. The proportion of women in the Commons now stands at 22.0 per cent, compared to 19.5 per cent in 2005. This has placed the UK slightly higher up the table of women’s representation in parliaments worldwide – 52nd place. However, Britain still trails far behind Rwanda, which is in first place with women’s representation at 56.3 per cent.

Britain also remains behind most Western European parliaments, which tend to have proportional electoral systems. It has been

estimated that at the current rate of change and under the current system it will take a further 200 years before we reach parity in the numbers of women and men in parliament.

| Election Year |

Number of women MPs |

% of Women MPs |

| 1979 |

19 |

3 |

| 1983 |

23 |

3.5 |

| 1987 |

41 |

6.3 |

| 1992 |

60 |

9.2 |

| 1997 |

120 |

18.2 |

| 2001 |

118 |

17.9 |

| 2005 |

128 |

19.5 |

| 2010 |

143 |

22 |

In 2005 three quarters of all female MPs represented the Labour Party; advancing observations that the level of women’s representation in the Commons was largely

dependent on Labour’s majority. Concerns were raised that the number of women in parliament could potentially decline if another party dominated in future elections, unless the proportion of women became more uniform across the parties.

Nevertheless, despite Labour losing its majority in the 2010 election, the number of women

in parliament has not decreased; although the composition of the lower chamber has changed. The House of Commons is now composed of more Conservative women and fewer Labour and Liberal Democrat women than in 2005.

| Party |

Number of Women MPs |

Increase /decrease from 2005 |

Proportion of parliamentary party |

| Labour |

81 |

-13 |

31.4 |

| Conservatives |

49 |

31 |

16 |

| Liberal Democrats |

7 |

-2 |

12.3 |

| Other |

6 |

– |

– |

High numbers of retiring MPs provided the opportunity for the three main parties to make real progress on women’s representation

in the 2010 election. Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have achieved a rate of 50 per cent women as candidates in seats

with retirements. In total 152 male and 28 female MPs retired and they were replaced as candidates by their parties with 87 men and

65 women.

The Conservatives have increased their number of women by thirty, which is a significant increase compared to 2005 (a percentage increase from 8.6 to 15.7). Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have lost female MPs from their ranks – thirteen and two respectively. However, since the overall number of Labour MPs has fallen, this means the proportion of female Labour MPs has increased from 27.5 per cent to 31.4 per cent. Although Labour has lost thirteen women, the party remains far ahead of the other parties in its proportion of women MPs. On the other hand, the Liberal Democrats appear

to be going backwards in terms of women’s representation; whereas in 2005 female Liberal Democrat MPs made up 16.1 per cent of the parliamentary party, in 2010 this has decreased to 12.3 per cent.

Despite an increase in the number of Conservative women, Labour still managed to retain the highest number of female MPs. There are two main factors behind the high number of Labour women: the party placed more women candidates in winnable seats; and they placed a large number of women candidates in safe seats where the previous Labour MPs was standing down.

Six female MPs were elected from the smaller parties – 1 for the Green Party; 1 for Sinn Fein; 1 for the SNP; 1 for the SDLP; 1 Independent; and 1 for the Alliance Party.

Women: party representation

There were 877 women out of a total of 4,134 candidates in the 2010 general election. Although this figure was higher than in previous elections, it still only amounted to 21 per cent of the total number of candidates.

It is logical to expect that a higher number of female candidates will translate into a higher number of women MPs and the recent general election has been no exception to this logic. In 2001 women made up 19 per cent of the total number of candidates; in 2005 this rose to 20 per cent; and in 2010 this increased again to 21 per cent, which resulted in the 2010 election producing the highest number of women MPs in the UK to date.

| Party |

No. of women candidates |

Proportion of total party candidates |

Number of women MPs |

| Labour |

190 |

30.3 |

81 |

| Conservatives |

152 |

24.1 |

48 |

| Liberal Democrats |

134 |

21.3 |

7 |

However, there are several explanations why the number of women candidates did not convert into more women MPs. First,

although selection processes aim to increase the number of female candidates, in order to significantly increase the number of women in parliament under the First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system these candidates need to be placed in winnable seats. For example, if we take a look at the disproportional number of Liberal Democrat women MPs compared to the number of Liberal Democrat women candidates this indicates that a large number of these candidates were not placed in winnable seats. Secondly, in seats that are contested between female candidates, this places significant limits on the number of women who can be elected. For example, Bolton West saw Julie Hilling, Jackie Pearcey and Susan Williams all contesting the same seat and Brighton Pavilion saw Caroline Lucas, Nancy Platts, Charlotte Vere and Bernadette Millam all standing. In total there were 11 seats around the UK where candidates from the three main parties were all women, whereas in 262 seats the candidates from the main parties were all men.

The Sex Discrimination (Election Candidates) Act 2002 allowed political parties to use positive action in the selection of election candidates, should they wish to do so. This Act has now been amalgamated into the Equality Act 2010, which extends the provision to exempt political parties from sex discrimination law until 2030. For Westminster elections, Labour is the only party to use this provision and the policy of all-women shortlists has remained important in addressing the gender imbalance in the Parliamentary Labour Party.

The marked increase in the number of Conservative women MPs – although not due to the use of all-women shortlists – can be attributed to a determined effort by the Conservative Central Parliamentary Selection Board to place more women on their list of candidates, combined with a national swing towards the Conservative party.