Introduction

Darren Hughes, Chief Executive

The last nine years have witnessed three general elections, a nationwide referendum and no less than five prime ministers. At times our politics has felt chaotic, and the output of the Westminster electoral system has only added to this sense of dysfunction.

Increasingly we are seeing the system failing on its own terms. Failing to produce the single-party, stable government that is supposed to be its strength.

In 2010 First Past the Post delivered us a coalition government, the first since 1945, under a system designed to produce single-party majorities. In 2015, First Past the Post gave us the most disproportionate election to date with a majority government secured with under 37 percent of the vote share. In 2017, despite over 80 percent of votes going to just two parties (the highest combined vote share since 1970), First Past the Post could not deliver a majority government. And in 2019 a huge majority was delivered with the difference between a hung parliament and large majority resting within a polling margin of error.

With two of the last four elections having the highest ‘voter volatility’ since 1931 and each of our nations having different, multi-party contests, these general elections have shown just how erratic the Westminster system can be in this context – it is a system no longer fit for UK politics.

This report draws together our analyses of the last three general elections looking at the impact of First Past the Post on election outcomes. There are huge differences in how the system treats voters, throwing out increasingly distorted results. This should give pause for thought for all sides of politics. First Past the Post is damaging our democracy, it’s time to change.

Seat share, vote share

The 2019 General Election results

Some parties benefit from First Past the Post, while others lose out.

The last three general elections have seen a winning majority gained on just 36.9 percent of the vote, a minority government on 42.4 percent of the vote and an 80-seat majority achieved on a vote share increase of just 1.3 percent.

In 2019 the Conservative Party was rewarded with a majority of seats (56.2%) on a plurality of the vote (43.6%) – with a 1.3 percentage point increase on its 2017 vote share giving the party a 7.4 percentage point increase in seats. The previous election had seen the Conservatives reduced to 318 seats despite a 5.5 percent increase in their vote share, leaving them short of a majority. In 2017, on 42.4 percent, the Conservatives had not only increased their vote share (up from 36.9 percent in 2015), they had achieved the same vote share as in 1983 – a year which saw a landslide 397 Conservative MPs elected. And yet, the Prime Minister returned to parliament having lost her majority.

Changes in Conservative Party share of votes and seats 2015-2019.

Small changes can make a big difference, but an increase in support doesn’t always mean an increase in seats.

These unusual elections came on the back of the 2015 election which – on top of being the most disproportionate result in British election history, saw the Conservatives win a majority of seats on just 36.9 percent of the vote and Labour lose seats despite increasing their vote share.

These unexpected and erratic results have all been delivered by a system defended on the basis that it delivers strong, single party governments. Recent elections have suggested otherwise.

As in 2015, the 2019 general election saw an increase in vote share for smaller parties – from 18 percent in 2017 to around 25 percent in 2019 – reflecting the long-term trend towards multi-party politics across the UK (in 2015 the number of votes cast for parties other than the Conservatives, Labour or Liberal Democrats was 24.8 percent, up from 11.9 percent in 2010). This support for other parties came despite the significant two-party squeeze which took place during the 2019 campaign. Labour and the Conservatives had struggled for a combined 50 percent in the polls earlier in the year, yet the combined final vote share of the election for both parties ended up at 75 percent.

Share of votes and seats for political parties 2015-2019.

The relationship of votes to seats is different for different parties.

Big changes in voting behaviour can have little impact on Westminster.

Changes in share of votes and seats for political parties 2015-2019.

The Speaker is included in the Conservative totals in 2015 and 2017. For full results please see Appendix 2.

An increase in vote share doesn’t always result in an increase in seat share. It can result in a decrease.

England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

Around the UK

Not only does First Past the Post over-represent parties whose vote is geographically concentrated within constituencies, it exaggerates our regional and national differences. The 2015 general election saw, for the first time, different parties gaining the most seats in each of our four nations. This trend has continued with the Conservatives in England, the SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales and the Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland gaining the most seats in 2017 and 2019.

In England, the two largest parties dominate with votes for other parties routinely squeezed. In 2019, over five million votes went to parties other than Labour and the Conservatives (nearly 18.9% of the vote) yet resulted in just 1.7 percent of the seats in England. In Scotland, multi-party politics has been translated into single party predominance in both 2015 and 2019 with the SNP gaining 81 percent of the seats on a 45 percent vote share in 2019. In Wales, Labour continues to dominate. In 2017, 48.9 percent of the vote for Labour in Wales translated into 70 percent of the seats. And in Northern Ireland, again multi-party politics is forced into a two-party shape. In 2017 all but one Westminster seat went to two parties despite over a third of voters in Northern Ireland voting for others. In 2019, 83 percent of seats went to two parties despite 47 percent of votes going to other parties in Northern Ireland.

Votes needed per MP

By Party

The number of votes required to elect one MP for each party in the 2019 general election.

For some parties, votes are not translating into seats. Huge numbers of votes have no impact on Westminster.

The number of votes needed to elect an MP has differed quite significantly for each party across these elections. In 2019, on average, it took 38,264 votes to elect a Conservative MP, while it took 50,835 votes for a Labour MP. Strikingly, it took 865,697 votes nationally to elect just one Green Party MP and 336,038 votes for a Liberal Democrat – demonstrating how punitive Westminster’s warped system is on parties whose votes are not concentrated in specific constituencies but spread out across the nation. The Brexit Party did not win any seats, despite having received 644,255 votes nationwide, while it only took 25,882 votes to elect an SNP MP.

Similarly in 2017, the Liberal Democrats’ 7.4 percent of the vote translated into just 12 seats (less than 2% of seat share) and the Greens only retained their one seat despite attracting over half a million votes – the largest votes per MP ratio. UKIP also attracted over half a million votes but no MPs in return.

In 2015 over ten million people voted for the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the Scottish National Party (SNP), the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru, the Green Party and other smaller parties – a third of all votes cast. Whilst the SNP returned 56 MPs on 4.7 percent of the vote, the other parties together took just 4.6% of the available seats.

Support for UKIP surged in the 2015 election, making the party the third largest on vote share nationally (12.6%), overtaking the Liberal Democrats (who dropped from 23% to 7.9%). Yet this delivered UKIP just one Member of Parliament. The Conservative party received three times as many votes but 331 times as many MPs.

Deviation from Proportionality

DV Scores

A well-established measure of disproportionality is the Deviation from Proportionality (DV) score. The DV score shows the extent to which an election result deviates from what it would look like if seats were proportional to votes gained by each party. It gives a percentage of seats in parliament which are ‘unearned’ in proportional terms, and which the party would not have obtained under a more proportional voting system.

There are various ways of measuring DV scores. We have used the Loosemore-Hanby index, which is calculated by adding up the difference between each party’s vote share and their seat share and dividing by two. This gives a ‘total deviation’ score of the results overall – the higher the score, the more disproportionate the result.

The DV score in 2019 for the UK overall was 16, which is higher than the 2017 election’s score of nine but much more in line with the DV scores for previous elections. The low DV score in 2017 can in part be explained by the ‘two-party’ squeeze at that election and consequent more proportional results (especially for Labour).

The DV score for the 2015 general election was 24, while for the 2010 election it was 22. The prior post-war record was 23 in 1983.

Levels of disproportionality (DV scores) for UK general elections, Scottish parliament, Senedd Cymru and London Assembly elections 1997-2021

The higher the number, the less proportional the result. Westminster elections under FPTP are generally significantly more disproportional than PR elections in the UK.

Ignored votes

Under First Past the Post

Under Westminster’s one-party-takes-all voting system, only a small subset of votes secure representation – those that are decisive in securing a candidate’s election. Votes cast for non-elected candidates and votes cast for winning candidates which are over and above the number they need to be elected, are thrown on the electoral scrapheap and do not influence the outcome of the election.

Around three-quarters of all votes are ignored in this way under the Westminster system. At the 2019 general election, 70.8 percent of votes did not directly contribute to electing an MP. In 2017 it was 68 percent of all votes and 74 percent and 71 percent in 2015 and 2010 respectively.

Key terms for this chapter

Decisive Votes:

Votes cast that a candidate needed to be elected.

Unrepresented Votes:

Votes cast for candidates that weren’t elected.

Surplus Votes:

Votes cast for a candidate above what was needed for them to be elected.

Ignored Votes:

All the votes that made no difference to the result as they were either Unrepresented or Surplus votes.

In 2019, 14.5 million people (45.3% of all voters) cast their vote for a non-winning candidate (unrepresented votes). Voters in Scotland and Northern Ireland fared particularly badly, with the choices of 54 percent (Scotland) and 55 percent (NI) of voters going to non-elected candidates. This means that over half of voters in these areas do not have an MP they voted for. The higher percentage of unrepresented votes in these nations is a consequence of using a system designed for two party contests when there are multiple parties contesting elections. Similarly in 2015, 50 percent of votes UK-wide went to non-elected candidates, as did 44 percent in 2017.

Percentage of decisive votes, unrepresented votes and surplus votes in 2019

by party.

Parties with geographically concentrated supporters tend to do better under First Past the Post.

Looking further at the proportion of votes going to non-elected candidates by party, reveals how the voting system has treated voters of different parties unfairly. Overall, across the UK in the 2019 general election, over half (50.6%) of Labour voters saw their votes go unrepresented, compared to just under a quarter (24%) of Conservative voters.

Supporters of parties with strength spread more thinly throughout the UK fared even worse. The Liberal Democrats achieved nearly 3.7 million votes, yet 92 percent of their votes went unrepresented. Over 96 percent of 865,697 Green Party votes went unrepresented, while all the Brexit Party’s 644,255 votes did.

In addition, the increasing geographical concentration of votes for some parties means many more ‘surplus’ votes are piling up for winning candidates, over and above what they need to win. Constituencies with significant ‘surplus’ votes are seeing over 90 percent of votes ignored (by going to non-winning candidates or being surplus). Seven constituencies saw over 90 percent of the votes ignored in this way in 2019.

Constituencies with the highest number of ignored votes at general elections 2015-2019.

| Constituency |

Ignored votes |

Year |

| Bristol West |

61,730 |

2017 |

| Isle of Wight |

57,357 |

2017 |

| Sleaford & North Hykeham |

54,435 |

2019 |

| Bethnal Green & Bow |

54,033 |

2019 |

| South Northamptonshire |

52,913 |

2019 |

| Hornsey & Wood Green |

52,292 |

2017 |

| Poplar & Limehouse |

51,519 |

2019 |

| South West Surrey |

51,475 |

2015 |

| Saffron Walden |

50,965 |

2019 |

| West Ham |

50,870 |

2017 |

| North East Bedfordshire |

50,857 |

2019 |

| Mid Bedfordshire |

50,688 |

2019 |

| South Cambridgeshire |

50,679 |

2015 |

| Knowsley |

50,505 |

2019 |

| North Somerset |

50,500 |

2015 |

Constituencies with the highest number of unrepresented votes at general elections 2015-2019.

| Constituency |

Votes for non-winning candidates |

Year |

| Isle of Wight |

41,709 |

2015 |

| Bristol West |

41,318 |

2015 |

| East Lothian |

37,357 |

2019 |

| Edinburgh North & Leith |

37,309 |

2017 |

| Sheffield Hallam |

37,176 |

2019 |

| Twickenham |

36,424 |

2015 |

| Kingston and Surbiton |

36,004 |

2015 |

| Cambridgeshire South |

35,914 |

2019 |

| Linlithgow & Falkirk East |

35,706 |

2017 |

| Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk |

34,893 |

2015 |

| Richmond Park |

34,742 |

2017 |

| Edinburgh West |

34,687 |

2017 |

| Stroud |

34,348 |

2019 |

| Lanark & Hamilton East |

34,026 |

2017 |

| Milton Keynes South |

33,834 |

2017 |

Tactical voting

Working around the system

One of the most striking features of recent general elections has been the rise in both voters and parties trying to work around the system.

During the run up to the 2019 election we asked voters whether they intended to vote tactically. The percentage of voters thinking of opting for a tactical vote, instead of voting for their first choice of candidate or party, increased as we got closer to the election. Between August and November 2019 (the start of the official campaign) between 22 and 24 percent of voters said they would choose ‘the best-positioned party/candidate to keep out another party/candidate that I dislike’. Our final poll before the election found nearly a third of voters saying they would vote tactically in this way (30%).

After polling day, we asked voters whether they had in fact cast a tactical vote. In a large post-election poll, conducted by YouGov for the ERS, 32 percent of voters said they voted tactically. Tactical voting was slightly higher amongst those who had voted Labour or Liberal Democrat (36% and 39% respectively) compared to Conservative voters (30%).

These figures represent an increase on 2017 and 2015. When we asked the same question in 2017, we found that one in five voters (20%) said they would be choosing the candidate that was most likely to beat the one they disliked. In 2015 it was closer to one in ten (9%).

Electoral pacts have also played their part in recent elections. In 2019 the Brexit Party announced that they would not stand in any seat that the Conservatives won at the 2017 general election – half of all the seats in Britain – in a move to consolidate the pro-Brexit vote. On the other side of the Brexit debate, the Liberal Democrats, Green Party and Plaid Cymru formed a limited agreement that saw only one of their number stand in 60 seats in England and Wales. In Northern Ireland too, the SDLP and Sinn Féin stood down in three seats, in order to try to boost the prospects of each other’s candidates (and other Remain supporting candidates) in these seats.

In 2017 the Green party did not stand candidates in 183 of 650 constituencies (up from 77 contests that did not feature a Green Party candidate in 2015). The party confirmed that at least 22 candidates had stood aside ‘to increase the chance of a progressive candidate beating the Conservatives’. The Liberal Democrats also entered into ‘progressive alliance’ arrangements with the Green Party; 42 seats featured progressive alliance arrangements in which one or other party stood down. UKIP didn’t stand candidates in 272 seats compared to only 26 seats that were not contested by a UKIP candidate in 2015. The UKIP leader said he would put ‘country before party’ in not opposing pro-Brexit MPs.

Tactical voting websites and vote swapping have also become a feature of general elections campaigns. In 2019 at least five tactical voting websites were set up by different organisations offering tactical voting advice. And media coverage also focuses on these practices. Research conducted by academics at Loughborough University found that discussion of electoral process issues – including tactical voting, electoral pacts, party divisions, and electoral integrity – dominated media coverage throughout the 2019 election campaign. Electoral pacts, tactical voting sites and parties’ focus on who is best placed to ‘win here’ all detract from the basic democratic premise that voters should be able to vote for who they want to win.

Although a perhaps understandable reaction to the iniquities of FPTP, tactical voting is not something that voters should have to consider. They should be free to vote for their first-choice party without fear that their vote will not count. Party step asides and the need for tactical voting would be eliminated by a move to a proportional voting system.

Safe seats

A feature of First Past the Post

Another recurring feature of FPTP that was in evidence at all three of the last general elections was the large number of safe seats, where parties are almost certain to win. The certainty of safe seats can breed complacency among parties and lead to voters being taken for granted, with safe seats ignored during election campaigns while seats that may change hands are lavished with attention.

Before the 2019 election, the average UK constituency had not changed hands for 42 years, with 192 seats (30% of the total) last changing party in 1945 or earlier, and 65 seats (10% of the total) being held by the same party for over a century. These ‘one-party’ constituencies mean that other parties can build up substantial vote shares in particular areas, yet never achieve the representation they merit.

In 2019 and 2015 we were able to predict the outcome in half of all seats in Great Britain before a single vote had been cast. That the outcome in so many of Westminster’s seats could be confidently known before a single voter had gone to the polls is a sad reflection of how many votes are devalued by the system. Only 79 seats changed party hands in 2019, a small increase on the 70 seats that changed at the 2017 general election, but still representing just 12% of seats across the UK. The 2015 general election saw 111 seats switch party and the 2010 general election saw 117 seats change.

Changes in votes are not being represented by changes in the House of Commons, with many voters locked out of having a meaningful influence on our politics. Voters in safe or marginal seats experience a very different election to each other.

Our polling in the run up to the 2019 election revealed that those living in seats classed as marginal received far more election literature than those seats classed as safe for one party or another. Just one in four people (25%) in safe seats reported receiving four or more election leaflets or other pieces of communication through their door compared to almost half (46%) of those in potential swing seats. Nearly three times as many people in swing seats (14%) reported receiving 10 or more leaflets or other pieces of communication, compared to just five percent of those in safe seats.

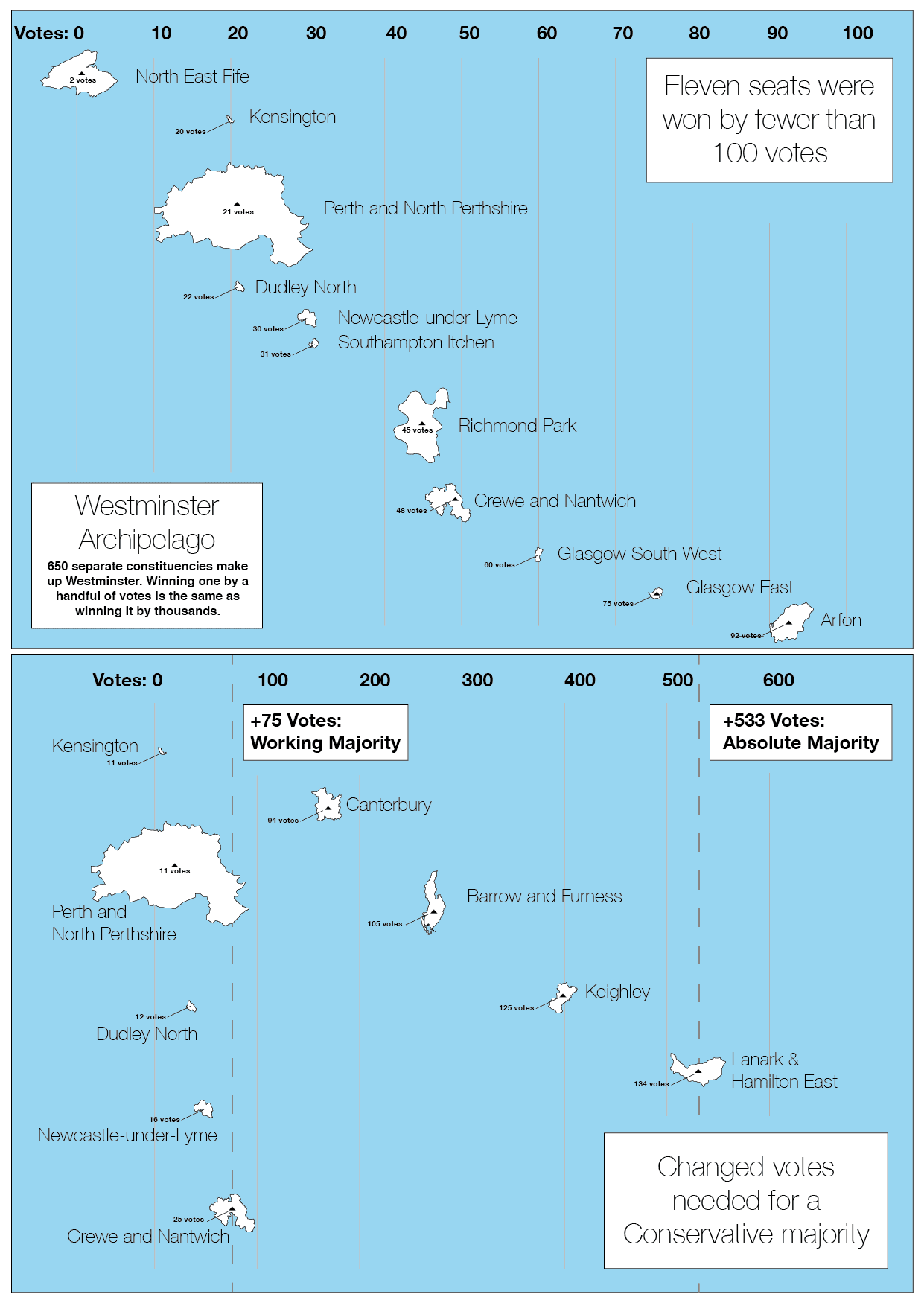

Whilst some seats have been safe for a century, others are highly marginal. The 2017 general election saw an increase in very marginal seats. Eleven seats were won by less than 100 votes. North East Fife was held by the SNP by just two votes. Such are the vagaries of the system that the Conservatives could have won an absolute majority on the basis of just 533 extra votes in the nine most marginal constituencies. A working majority could have been achieved on just 75 additional votes in the right places. Two very different outcomes based on less than 0.0017% of voters choosing differently in 2017.

By placing electoral outcomes in the hands of a small number of voters in a few select places, the electoral system not only gives some votes far more power than others, but is also creating an ever more unpredictable electoral environment. With a changing electorate and increasingly multi-party system, First Past the Post (an electoral system designed to produce single-party majorities in a two-party system) is failing.

Ultra-marginal seats at the 2017 general election (top) and how many votes were needed in key constituencies to form a working or absolute majority (bottom).

A small change in a few constituencies would have significantly changed the outcome of the election.

Smallest share of the vote needed to win

In seats where more than two parties are in contention, winners are frequently elected on a small percentage of the vote. The smallest of these in the last three elections was Belfast South at 24.5 percent of the vote in 2015.

Overall, in 2019, 229 of the 650 MPs were elected on less than 50 percent of the constituency vote – in other words, 35 percent of all MPs lacked majority support.

Smallest vote share for elected candidates 2015-2019.

Using FPTP in multi-party contests means the winning candidate is often far short of majority support.

Largest winning majorities

Another symptom of Westminster’s electoral system are candidates winning with huge majorities – piling up votes far beyond the amount needed to claim victory. Though indicative of a party’s support in specific areas, such large winning majorities mean that thousands of votes have no effect on the overall outcome.

The huge majorities won in these constituencies reflect a broader trend of certain votes consolidating in certain areas. The problem of this geographical concentration of votes for parties is that this increased support does not result in greater representation, only larger majorities for those MPs who have already crossed the line. FPTP rewards the most geographically efficient vote spread – which means it wastes a lot of votes which are geographically concentrated.

Largest majorities for elected candidates 2015-2019.

| Constituency |

Majority |

Year |

| Knowsley |

42,214 |

2017 |

|

East Ham

|

39,883 |

2017 |

| Hackney South & Shoreditch |

37,931 |

2017 |

| Bethnal Green & Bow |

37,524 |

2019 |

| Bristol West |

37,336 |

2017 |

| Camberwell & Peckham |

37,316 |

2017 |

| Liverpool Riverside |

37,043 |

2019 |

| West Ham |

36,754 |

2017 |

| Bootle |

36,200 |

2017 |

| Hackney North & Stoke Newington |

35,139 |

2017 |

| Lewisham Deptford |

34,899 |

2017 |

| Sleaford & North Hykeham |

32,565 |

2019 |

| North East Hampshire |

29,916 |

2015 |

| Maidenhead |

29,059 |

2015 |

| Esher and Walton |

28,616 |

2015 |

Under FPTP votes often stack up in safe seats creating bigger majorities for those MPs already over the line, but not more seats.

Alternative systems

Electoral systems

The 2019 General Election under First Past the Post. 650 constituencies elect a single MP each. Explore the full results at https://ge2019.electoral-reform.org.uk

The 2019 General Election under First Past the Post. 650 constituencies elect a single MP each. Explore the full results at https://ge2019.electoral-reform.org.uk

There are many electoral systems which fare much better than FPTP in terms of proportionality, voter choice, and representation. In other words, systems that work much better for voters.

ERS has projected the results of the 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections in Great Britain under a range of other electoral systems. These include Party List Proportional Representation (List PR), the Additional Member System (AMS), the Alternative Vote (AV) and the Single Transferable Vote (STV).

STV is used in Scottish local elections and all elections in Northern Ireland, apart from UK general elections. It is also currently being considered for local elections in Wales. AMS is used to elect the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Senedd and the London Assembly, while List PR was used in Great Britain for elections to the European Parliament and is the system currently being adopted for the Welsh Senedd.

A full methodological note for these projections can be found in Appendix A. It is important to note from the outset that it is impossible to predict with certainty what electoral results under different voting systems would be. The projections that follow are merely an indication of what the results of the last three general elections – conducted under FPTP – would have looked like using a different electoral system. It is of course impossible to account for the other changes that would accompany a switch to an alternative electoral system, such as changes in voter behaviour, party campaigning, or the number of parties standing candidates.

Additional Member System

The 2019 General Election under the Additional Member System. Larger constituencies elect a single MP each, with an equal number of regional MPs.

The 2019 General Election under the Additional Member System. Larger constituencies elect a single MP each, with an equal number of regional MPs.

The Additional Member System (AMS) – also known as Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP) outside of the UK – is a hybrid voting system. It combines elements of First Past the Post (FPTP), where voters choose one candidate to represent their constituency, and Party List Proportional Representation.

In AMS elections, voters choose a constituency candidate (elected under FPTP) and have a second vote for their preferred party to represent them regionally (under Party List PR). Voters can cast both votes for the same party or vote for different parties in their constituency and regional ballots. List seats are then allocated to parties on a proportional basis, usually applying some form of electoral threshold (generally 5%).

List seats ‘top up’ and partially compensate for the disproportionality associated with the FPTP element of the system, by taking into account how many constituency seats have already been won by a party. For example, if a region has 10 seats (five constituency seats and five list seats), and a party wins half the list votes and three constituency seats, then it should win an additional two list seats to reach the ~50% vote share it received.

The design of AMS systems can differ quite considerably. One significant difference is the ratio of constituency to list seats, which has consequences for the proportionality of this voting system. While the Scottish and Welsh versions of AMS are quite similar to each other, especially when compared to those used in Germany or New Zealand, they differ with regards to the proportion of constituency and list MPs. In Scotland, the proportion of ‘top-up’ list MPs is much higher than in Wales (43.4% compared with 33.3%), which means that the Scottish version of AMS tends to return a more proportional parliament. In our modelling, we have opted for a 50:50 ratio of constituency to list seats, which leads to a much more proportional outcome than the versions of AMS used in Scotland and Wales. We also applied a five percent electoral threshold.

Party List Proportional Representation

The 2019 General Election under Party List Proportional Representation. Each region elects a group of MPs, based on their population size.

The 2019 General Election under Party List Proportional Representation. Each region elects a group of MPs, based on their population size.

List PR systems vary depending on whether voters cast their vote for a party (closed list) or can vote for their preferred candidate within a list (open list). Between 1999 and 2019, closed List PR was used in Great Britain to elect members of the European Parliament (MEPs).

List PR systems score highly in terms of proportionality, but – especially in the closed list variant – they limit voter choice, because electors are forced to vote for a list pre-determined by a party and cannot nuance their choice by ranking candidates, as in preferential systems. Though the open list variant can increase voter choice, there is often a weaker constituency link in List PR systems as voters elect a slate of candidates from a larger area than under other electoral systems. Reducing constituency sizes might improve local representation, but this would then affect proportionality.

Single Transferable Vote

The 2019 General Election under the Single Transferable Vote. Larger constituencies, the size of a town or county, elect a group of MPs.

The 2019 General Election under the Single Transferable Vote. Larger constituencies, the size of a town or county, elect a group of MPs.

The Single Transferable Vote (STV) is a form of proportional representation which uses preferential voting in small, multi-member constituencies of around three to six MPs. It is used in Northern Ireland for all non-Westminster elections, Scottish local elections, the Republic of Ireland, Malta and the Australian Senate.

STV maintains a constituency link and strong representation, while enhancing voter choice and leading to much more proportional outcomes than FPTP. Under STV, each voter has one vote, but they can rank candidates in order of preference. Voters vote by putting a ‘1’ next to the name of their favoured candidate, a ‘2’ next to the name of their next favoured candidate, and so on. Voters can rank as many or as few candidates as they like. If a voter’s preferred candidate has no chance of being elected or has enough votes already, their vote is transferred to another candidate according to their preferences.

STV ensures that very few votes are ignored when compared with FPTP. It also ensures maximum voter choice, as electors can rank their choices both within and between parties and independents. As a slate of MPs is elected from a slightly larger area than under FPTP, STV also keeps the constituency link while ensuring that the diversity of opinion in the country is fairly represented in parliament.

Seat projections under different voting systems

We have calculated the results for GB only as the polling data to support these calculations does not cover the whole of the UK.

2015

2017

The Speaker is not included in the 2017 calculations.

2019

The Speaker is included in the 2019 Labour totals.

Appendix 1

Note on methodology

Projecting how results of First Past the Post elections would translate into seats under different electoral systems is an imperfect task. Using such results as a baseline means that any projection still incorporates FPTP’s deficiencies – such as tactical voting considerations and the lack of genuine multi-party competition – which would not be the case under more proportional systems.

There are some ways to mitigate against these restrictions to ensure that projections account for potential changes to voting behaviour under PR systems. In each of the previous general elections we have commissioned a post-election survey from YouGov to ask how people would have voted if they had been allowed to express additional preferences.

List PR methodology

For projections under this system, we followed the variant of List PR used in Great Britain for elections to the European Parliament (Northern Ireland used STV for these elections). We divided all 632 GB constituencies up into the 11 regions used for European Parliament elections, keeping the number of seats the same as those for Westminster elections.

Votes for each party were added up across constituencies for each region and seats were allocated on the basis of the D’Hondt formula, without applying an electoral threshold. The D’Hondt formula allocates the party with the most votes a seat in rounds, with a party’s votes divided by the number of seats it has won plus one. These rounds continue until all seats have been assigned.

Additional Member System methodology

AMS combines First Past the Post and List PR seats. The calculations used for our AMS projections thus involved a two-step process.

First, we allocated constituency FPTP seats. As we opted for a 50:50 ratio of constituency to list seats, these new AMS constituencies were usually created by combining two existing FPTP seats into a single AMS constituency. In some cases, because of an odd number of seats in a region, tricky geography or special exemptions (e.g. the Isle of Wight), single FPTP constituencies were kept. We added up a party’s total votes and calculated their new vote share in each AMS constituency. As these seats are allocated under FPTP, the party with the most votes in each constituency was the winner.

Second, we allocated list seats on the basis of regions. In 2017 we had a specific AMS polling question asking people how they would vote in a regional vote under such a system. In 2019 we recalculated parties’ vote shares on the basis of voters’ first preference results in the YouGov poll by region. This meant that, for example, if 90 percent of those who voted for the Conservative Party in London ranked the party as their first preference in the poll, then 90 percent of Conservative votes in that region were assumed to be a first preference. These ‘rejigged’ vote shares allowed us to recalculate the total votes each party received in that region.

We then used the D’Hondt formula to allocate seats to each party, based on the votes per region. We applied a five percent electoral threshold to each region and, as list seats are compensatory, we took into account how many seats each party obtained under the FPTP element to calculate the number of list seats to allocate.

Alternative Vote methodology

For the Alternative Vote projection we used the same 650 constituencies used in current FPTP elections.

We have tried to account for the impact of tactical voting by recalculating first votes according to first preference results in the poll by region. If, for instance, 90 percent of those who voted Conservative in London said they would rank them ‘1’ on their ballot then 90 percent of Conservative votes in each area were assumed to be a first preference. We then ran an AV vote in each constituency based on regional results.

In any seat where more than half the votes are won by one candidate, that candidate is deemed elected. In other seats, parties were eliminated in reverse vote order and votes were reallocated from parties on the basis of preferences (from the polling data), so that, for instance, if Party A were eliminated and 58 percent of Party A voters in our poll stated they second-preferenced Party B then a number of votes equivalent to 58 percent of Party A votes in that constituency would be added to the Party B total. This process is repeated until one party reached 50 percent of the votes. That party would then be deemed the AV winner.

Single Transferable Vote methodology

For our STV projections, it was necessary to work on the basis of new constituencies. These have been created by aggregating existing FPTP constituencies into new three- to six-member seats. STV constituencies were drawn up to reflect local communities as much as possible.

Parties’ votes were added up and their vote shares were calculated for each of these STV constituencies. We then recalculated each party’s vote share in an STV constituency on the basis of first preference results in the YouGov poll. This was done by region, meaning that the same ‘rejigged’ formula was applied to each STV constituency in an existing government office region.

We then proceeded to allocate seats using the droop quota, which means that, to win a seat, a candidate must receive a vote equivalent to the total number of votes cast divided by the number of seats to be allocated plus one. For example, in a three-seat constituency, the droop quota is equivalent to 25 percent. Any party which reached the quota was allocated a seat. Seats were awarded on the basis of how many quotas of support (e.g. combinations of 25%) a party won. So, a party winning 50 percent of the vote in a three-member constituency was allocated two seats.

If no party achieved the quota, the party with the lowest vote share was eliminated and its vote share was redistributed to other parties using a formula based on the second preference results in the poll. This process continued until all seats were allocated. In very limited cases when awarding the final seat, no party reached a full quota so the party with the highest vote share was awarded the seat.

This modelling is of course only an approximation of the allocation of seats and transfers under STV and relies on a limited number of preferences (in a real-world STV election it is likely that a voter would rank more than two candidates/parties). But it does give an indication of how votes would transfer under STV and offers an insight into how voters’ choices would be translated into seats.

Appendix 2

Results tables

UK general election results, 2019

| Party |

Votes (%) |

Vote change from 2017 (%) |

Seats (%) |

Seat change from 2017 (%) |

| Conservative |

43.6 |

+1.3 |

56.2 |

+7.4 |

| Labour |

32.1 |

-7.9 |

31.1 |

-9.2 |

| Lib Dem |

11.5 |

+4.2 |

1.7 |

-0.2 |

| SNP |

3.9 |

+0.8 |

7.4 |

+2.0 |

| Green Party |

2.7 |

+1.1 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

| Brexit Party |

2.0 |

+2.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Others (including the Speaker) |

4.3 |

n/a |

3.6 |

n/a |

UK general election results, 2017

| Party |

Votes (%) |

Vote change from 2015 (%) |

Seats (%) |

Seat change from 2015 (%) |

| Conservative |

42.4 |

+5.5 |

48.9 |

-2.0 |

| Labour |

40.0 |

+9.5 |

40.3 |

+4.6 |

| Lib Dem |

7.4 |

-0.5 |

1.8 |

+0.6 |

| SNP |

3.0 |

-1.7 |

5.4 |

-3.2 |

| UKIP |

1.8 |

-10.8 |

0.0 |

-0.2 |

| Green Party |

1.6 |

-2.1 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

| Others |

3.7 |

n/a |

3.4 |

n/a |

UK general election results, 2015

| Party |

Votes (%) |

Vote change from 2010 (%) |

Seats (%) |

Seat change from 2010 (%) |

| Conservative |

36.9 |

+0.8 |

50.9 |

+3.8 |

| Labour |

30.4 |

+1.4 |

35.7 |

-4.0 |

| UKIP |

12.6 |

+9.5 |

0.2 |

+0.2 |

| Lib Dem |

7.9 |

-15.2 |

1.2 |

-7.6 |

| SNP |

4.7 |

+3.1 |

8.6 |

+7.7 |

| Green Party |

3.8 |

+2.8 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

| Others |

3.7 |

n/a |

3.0 |

n/a |

Seat projections under different voting systems, General election 2019 (Great Britain)

| Party |

FPTP |

STV |

AMS |

List PR |

| Conservative |

365 |

312 |

284 |

288 |

| Labour |

203 |

221 |

188 |

216 |

| SNP |

48 |

30 |

26 |

28 |

| Lib Dem |

11 |

59 |

79 |

70 |

| Plaid Cymru |

4 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

| Green Party |

1 |

2 |

38 |

12 |

| Brexit Party |

0 |

3 |

12 |

11 |

| Others |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| Total |

632 |

632 |

632 |

632 |

Seat projections under different voting systems, General election 2017 (Great Britain)

| Party |

FPTP |

STV |

AMS |

AV |

| Conservative |

317 |

282 |

274 |

304 |

| Labour |

262 |

297 |

274 |

286 |

| SNP |

35 |

18 |

21 |

27 |

| Lib Dem |

12 |

29 |

39 |

11 |

| Plaid Cymru |

4 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

| Green Party |

1 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

| UKIP |

0 |

1 |

11 |

0 |

| Total |

631 |

631 |

631 |

631 |

Seat projections under different voting systems, General election 2015 (Great Britain)

| Party |

FPTP |

STV |

AV |

List PR |

| Conservative |

331 |

276 |

337 |

242 |

| Labour |

232 |

236 |

227 |

208 |

| SNP |

56 |

34 |

54 |

30 |

| Lib Dem |

8 |

26 |

9 |

47 |

| Plaid Cymru |

3 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

| UKIP |

1 |

54 |

1 |

80 |

| Green Party |

1 |

3 |

1 |

20 |

| Total |

632 |

632 |

632 |

632 |