Foreword

By Katie Ghose, Chief Executive, ERS

What is the role of referendums in our democracy? For some, referendums are a means for demagogues to undermine parliamentary sovereignty. For others, they’re a vital exercise in engaging citizens on crucial constitutional issues that can’t be settled by parties alone.

Yet referendums aren’t good or bad in themselves; they are a democratic tool with positives and negatives. The quality of information and debate can vary enormously.

It’s partly because referendums aren’t ever a pure exercise confined to the ‘exam question’. There’s always a proxy element: voters often choose to cast judgement about the government of the day, or to opt for one of the many de facto mini-manifestos that lie behind each side.

Nowhere have we seen these issues more clearly reflected than during the EU referendum. As passionate believers in democracy, we wanted to see the best possible referendum debate. The Electoral Reform Society chose to play an active role in the EU referendum by trying to ensure the debate was as high-quality as possible, and learn important lessons in how good deliberation can be stimulated in living rooms, community centres and workplaces across the country. Our Better Referendum online toolkit (see pp 33-39), organised with university partners, took advantage of digital technology to enable free, deliberative discussion to be a part of the EU referendum.

Many people felt as if this was the first vote they had ever cast where they knew it would count. No safe seats, no tactical voting, no electoral quagmires. Unlike First Past the Post general elections, this was a vote where the public felt empowered – and they turned out in large numbers. At the ERS we’ve seen a membership surge on the back of this, with hundreds of people joining to say that votes should count in all elections, not just referendums.

Nonetheless, many also felt the campaign failed to provide the public with the best possible debate, in contrast to what is widely viewed as a vibrant Scottish referendum vote. There were a large range of problems with the referendum campaign, many of which are explored in this report. Among them is the short length of the campaign – political anoraks felt the campaign had been going on for ever before most people had woken up to its existence. Moreover, the failure to give 16- and 17-year-olds the vote, unlike in the Scottish referendum, was a huge missed opportunity to invigorate the debate.

However, we know that referendums are rarely the end of the matter. And neither should they be. This vote showed there is a huge appetite out there for the public to engage in crucial constitutional issues – and that appetite hasn’t gone away simply because 23rd June 2016 has been and gone.

The context of a referendum is everything. If they are simply snapshots of public opinion, taken without any real effort to engage the public properly in the issues, then all sorts of problems can arise. But if they take place within a wider process of informed debate and active citizenship, they can be the catalyst for real political engagement and good democracy.

We now need to keep the conversation going after the referendum and ensure that the public have a say in what comes next. Democracy shouldn’t end after polling day – voters clearly had a strong appetite for expressing their views on this issue. Now it’s essential to ensure the fullest possible public involvement in the Brexit negotiations.

This report draws on the ERS’s extensive polling, conducted by BMG Research throughout the referendum, spanning from the very start of the campaign in February to a week before voters went to the ballot boxes. We assess voters’ perceptions of the referendum debate, but more than that – we use it to see where we should go from here to ensure that in the future, voters get the referendums they deserve.

We see this report as a foundation for a full review of referendums in the UK. Rather than jumping from plebiscite to plebiscite with no framework for deciding how, when and why they should happen, it’s time for a national conversation on the role of referendums in British politics.

Introduction

The people have spoken. Or have they?

Those committed to improving our democracy can no longer ignore the elephant in the room. Referendums have become a central feature of our politics. Since 2011 we have had two UK-wide referendums (on voting reform and membership of the European Union), a Scottish independence referendum, and a Welsh referendum on further devolution of powers.

That represents a significant acceleration from previous years – there was only one prior UK-wide referendum (on membership of the European Community in 1975), and other referendums on devolution to the nations are mainly concentrated into the two years after the 1997 Labour government came to power with its promises of devolution.

The UK is in an extended period of constitutional flux, and is showing few signs of coming out the other side any time soon. The terms of Brexit must be decided, and conceivably ratified by Parliament, the public or both; Scotland looks ever closer to independence; devolution of power to more local levels of government than Westminster is widely supported, but the path is unclear; the question of English governance remains live; and so on. Given this state of uncertainty about our constitution, it is a fairly safe bet that we will see referendums again in the near future.

Referendums are a rich source of learning about public attitudes to politics and democracy. They expose views and feelings that are not given true expression or representation at general elections, given our distorted electoral system. At the Electoral Reform Society we have heard time and again from members of the public for whom 23rd June was the first time their vote had truly counted.

But there are also serious questions to be asked about the place of referendums in our politics. How do they sit alongside other aspects of our democracy, particularly our parliamentary system? Should there be an agreed trigger for referendums? How should they be conducted and regulated so as to ensure they are more of a positive contribution to our democracy than a negative one? Do we accept that constitutional issues are principally a matter for governing parties (acting on manifesto commitments or coalition deals) or should we consistently seek a citizen-led approach? And when referendums happen, how do we ensure high quality public information and debate before people actually get to the polling booth? Finally, what are the wider conditions in our political culture which would provide the best foundations for referendums to take place in the future?

This report is an initial attempt at addressing some of these questions. It does so through a detailed analysis of this year’s EU referendum, focusing particularly on how the campaigns were received by the public and on alternative methods and platforms for public engagement. Our main findings are:

- Information People felt consistently ill-informed – yet this was not for lack of interest: voters expressed high levels of interest throughout the campaign. This shows a need for action in future to ensure that rates of interest are matched by extensive public information campaigns and a vibrant deliberative debate, including the possibility of holding official Citizens’ Assemblies during the campaign.

- Personalities The ‘big beasts’ largely failed to engage or convince voters to their side, with many voters appearing switched off by the ‘usual suspects’. This suggests that far more important than major political figures being wheeled out is having a strong narrative based on policies not personalities, which inspires people to debate the issues for themselves.

- Negative campaigning As the race wore on, the public viewed both sides as increasingly negative. It is not clear that either side gained from this approach.

- The need for real deliberation There is an appetite for informed, face-to-face discussion about the issues, but this can only be nurtured within the context of a longer campaign.

Above all, our analysis has demonstrated the need for a much greater level of citizen involvement and deliberation, not only during referendums themselves but throughout the workings of our wider democracy. An informed and engaged electorate is the first step towards a political system that can tolerate the divisive aspects of a binary referendum debate. We should therefore do everything we can to foster higher levels of deliberation and engagement, both during referendum campaigns and in our wider political culture.

Given our findings, we are calling for a root and branch inquiry into the conduct of referendums in the UK. Within that inquiry, we would like to see the following specific recommendations to be considered:

Laying the groundwork

- There should be mandatory pre-legislative scrutiny for any parliamentary Bill introducing a referendum, lasting at least three months. This should include real citizen involvement through a randomly selected Citizens’ Select Committee and/or a wider consultation process.

This would give citizens and all parties an opportunity to shape the referendum process and rules in order to maximise the chances for an informed and engaged campaign.

- All referendums should have a minimum six-month regulated campaign period.

This will allow the public enough time to get to grips with the issues and make a low-information, low-deliberation referendum campaign less likely.

- As soon as possible after a referendum Bill has been passed, The Electoral Commission should publish an official ‘rulebook’ setting out the timetable, rules for campaigners and all other technical aspects of the vote.

This should be the ‘bible’ for the referendum, to minimise controversy around the administration of the vote.

Better information

- Citizenship education should be extended in primary and secondary schools, alongside the extension of votes at 16 to all public elections and referendums, and accompanied by a key role for schools in voter registration.

This would lay the groundwork for a more informed and engaged electorate better equipped to deliberate on the issues around a referendum.

- At the start of the regulated period the Electoral Commission, or a specially commissioned independent body, should publish a website with a ‘minimum data set’ containing the basic data relevant to the vote in one convenient place. (See Albert Weale, Is there a future for referendums? Constitution Unit blog, 25th July 2016.)

A major source of complaint about the conduct of the referendum was the supposed lack of independent information available about the vote. While there are real difficulties in separating out fact from political argument in these cases, a minimum data set ought to be possible.

- An official body – either the Electoral Commission or an appropriate alternative – should be empowered to intervene when overtly misleading information is disseminated by the official campaigns.

Misleading claims by the official campaigns in the EU referendum were widely seen as disrupting people’s ability to make informed and deliberate choices. Other countries including New Zealand have successfully regulated campaign claims – the UK should follow suit.

More deliberation

- There should be an official, publicly funded resource for stimulating deliberative discussion and debate about the referendum.

Initiatives which equip people with the information and platforms needed to deliberate on the issues around the referendum should receive official support.

- The Electoral Commission or an appropriate alternative should provide a toolkit for members of the public to host their own deliberative discussions about the referendum.

Our ‘Better Referendum’ intervention demonstrated a widespread appetite for members of the public to get together in a high-information environment to discuss the issues. Similar deliberative tools should be rolled out as part of any public engagement initiative.

- Public broadcasters should consider more deliberative – rather than combative – formats for referendum-related programming. And Ofcom should conduct a review into the appropriate role for broadcasters in referendums.

While there is clearly a place in our politics for TV debates and traditional political journalism, the binary nature of referendums demands more space to be made for more reflective and discursive formats.

Our report starts by examining the question of ‘information’ – to what extent did people feel well informed about the referendum, where did they get their information from, and how trusted were these sources of information? This provides a basis for understanding the way in which the referendum campaign was received by the public, and how to improve the processes for disseminating information. We then turn to the campaigns themselves, looking at how they were received by the public and asking what role campaigns and the media can realistically play in improving the level of public debate. Then we present an alternative model of public engagement which emphasises careful, considered debate among members of the public, and we ask whether this sort of deliberation ought to be part and parcel of future referendum processes. Finally we examine the wider context of referendums from the UK and around the world, to support the case for our recommendations.

In one sense, a referendum offers the clearest possible indication of the popular will. But in another, the waters are easily muddied. The EU referendum result was decisive, formally unchallenged and with a relatively high turnout. The public’s decision was clear. But there are many concerns about the way the campaigns conducted themselves, the nature of the question being put to the British people, and the relationship between the result of the referendum and the ongoing proceedings of Britain’s parliamentary democracy.

These doubts have raised serious questions about the place of referendums in our politics. This report sets out the conditions for helping ensure that referendums are a positive aspect of our democracy. Given the increasing frequency of their use in the UK, it is more important than ever that we look at the EU vote and ask: how do we ensure future referendums in the UK are the best they can be?

The Information Battle

Well informed?

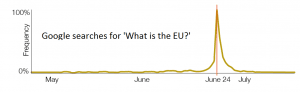

On 24th June, the morning after Britain voted to leave the European Union, the number of people in the UK googling the phrase “what is the EU” soared. Compared to the previous days and weeks of the campaign, interest in finding out about the EU went stratospheric.

Figure 1: How often was the phrase ‘What is the EU?’ Googled in the UK?

Source: Google Trends

This fact alone suggests that, when it came to the day of the vote, many members of the public did not feel well informed about the issues at the heart of the referendum. And our polling over the course of the campaign confirmed that that was indeed the case, even with just a week to go before a pivotal vote on Britain’s constitutional future.

At the start of the campaign in February, only 16% said they were well informed or very well informed about the referendum. This rose to 33% by a week before the referendum. Meanwhile 46% said in February they were poorly informed or very poorly informed, dropping to 28% in our final poll. While our final poll was taken eight days before the referendum and therefore we might expect voters to become more informed by polling day, nonetheless these are low levels of informedness.

Figure 2: How well informed do you feel about the upcoming EU referendum?

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society

For comparison, a December 2013 Ipsos MORI Scottish poll found that 56% felt informed about the Scottish independence referendum – and this was a full nine months before the day of the referendum itself. And a poll by Survation in April 2014 – still five months out from the referendum – found 59% agreeing that they could make an informed decision on Scottish independence. While self-reporting of ‘informedness’ isn’t completely reliable, it gives a good indication of the state of the debate.

A well informed public is a fundamental requirement for a good democratic culture, particularly when people are asked to make a direct decision via a referendum. We would argue that the levels of knowledge reported by members of the public during the EU referendum were too low throughout. The date of the referendum was announced in late February, giving the electorate just four months to get to grips with the issue at hand. If levels of information about the European Union had already been reasonably high at this stage, perhaps this timeframe would have been adequate. We did, after all, see a doubling of the number of people saying they were well informed over the course of the campaign. But 16% (the proportion of people who said they were well informed in February 2016) is not a large number from which to start. This suggests the need for ensuring referendum campaigns last long enough for members of the public to become fully informed and engaged.

A question of salience

In political systems where plebiscites are more common, such as Switzerland and California, the effects of referendums may in fact be to lower public participation. Since the start of 2015, the Swiss have held 15 national referendums on four different dates as well as numerous others at local and canton (regional) level. Typical turnouts are around 45%, with the highest (63.7%) on a vote on expelling foreign criminals. What’s more, parliamentary turnouts are low – the last above 50% was in 1975. That is at least partly because referendum-heavy cultures ask many more questions of the public, and therefore these questions may often be of less national importance than the type of question put to the British public in their occasional referendums. One might dispute, for instance, whether a referendum to decrease the licence fee for public broadcast by 62 Swiss francs was ever going to trigger real political engagement. Constant referendums also run the risk of ‘electoral fatigue’ as too many elections can cause a sense of lesser importance being attached to the process of voting. However, evidence from the US does show slight increases in political turnout and knowledge, although it is worth noting that referendums are typically held alongside elections in the US (hence boosting turnout by expanding the pool of interested voters) and that political knowledge does not appear to increase amongst non-voters.

In the case of the EU referendum, its importance could hardly be overstated. And this was reflected in the levels of interest in the referendum shown by members of the public.

Figure 3: How interested would you say you in the EU referendum? (April 2016)

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society

With 30% saying they were very interested, and a further 39% interested – and this a full two months before the referendum itself – clearly the question of EU membership sparked people’s interest, contrary to oft-repeated narratives about the public being overwhelmingly ‘bored’ by the issue. The eventual voter turnout of 72% – the highest turnout in a UK-wide ballot since the 1992 general election – underlines this point. Just as in the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, the public appetite for grappling with this crucial constitutional issue was undoubtedly present. But unlike in Scotland, there appeared to be a significant ‘information gap’ coupled with the lack of an extensive grassroots debate, which hindered people’s engagement in the issues around the referendum.

Sourcing the 'facts'

When we asked people where they were getting their information from, their answers remained broadly static over the course of the campaign – with the exception of a big uptick for the Leave campaign between March and May. The BBC proved, predictably, to be the most common source of information every time we asked this question, and newspapers, other media, social media and friends and family also proved important.

The fact that the influence of the Government and newspapers on voters remained almost exactly the same – despite endorsements from newspapers for both sides and a significant increase in government output on the referendum in the run-up – suggests there may have been a certain level of distrust of these outlets, or in the case of newspapers which took a stance, that people were not significantly swayed or that their views already matched with their paper’s.

Figure 4: Important sources of information

|

Mar-31

|

Apr-26

|

May-25

|

Jun-17

|

|

BBC

|

34%

|

33%

|

30%

|

34%

|

|

British Government

|

8%

|

10%

|

8%

|

8%

|

|

British Newspapers

|

20%

|

20%

|

17%

|

20%

|

|

British Television & Radio Broadcasters (Excl BBC)

|

15%

|

17%

|

13%

|

17%

|

|

The Remain Campaign

|

5%

|

6%

|

8%

|

9%

|

|

The Leave Campaign

|

8%

|

13%

|

17%

|

17%

|

|

Political Parties

|

6%

|

7%

|

6%

|

7%

|

|

Social media

|

10%

|

14%

|

14%

|

16%

|

|

Family

|

13%

|

18%

|

13%

|

18%

|

|

Friends

|

9%

|

14%

|

13%

|

16%

|

|

Colleagues

|

4%

|

7%

|

6%

|

4%

|

|

None of the above

|

22%

|

17%

|

20%

|

18%

|

|

Don’t Know

|

15%

|

12%

|

12%

|

9%

|

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society. Question: Which of the following have been most important in informing your decision about the EU referendum so far? Please select up to three of the following options.

This distrust was reflected in widespread reports of people who felt the media – and by extension the campaigns which were directing their communications via the media – were not providing them with the accurate information which they craved. Serious concerns and hesitations among the electorate about both the Remain side’s so-called ‘Project Fear’ and the Leave side’s use of selected statistics were commonplace. The high proportion of people using the BBC as an important source of information suggests that people were seeking an impartial outlet to weigh up the issues. These results, combined with the low levels of information reported by voters (see Figures 2 and 3), suggest the campaigns were not doing enough to provide high-quality information for voters.

There are also some worrying demographic divides in terms of information sources (see Figure 5). For example, the percentage of those overall influenced by Leave went up from 8% in Feb to 17% in June – but within that, 25% of over 65s viewed the Leave campaign as their most important source of information, compared to only 13% of 18-24 year olds.

Figure 6: Important sources of information by age and social class, June 24th

|

18-24

|

65+

|

ABC1 |

C2DE

|

|

BBC

|

24%

|

41%

|

39%

|

27%

|

|

British Government

|

15%

|

5%

|

8%

|

7%

|

|

British Newspapers

|

16%

|

29%

|

22%

|

16%

|

|

British Television & Radio Broadcasters (Excl BBC)

|

17%

|

21%

|

18%

|

15%

|

|

The Remain Campaign

|

10%

|

11%

|

9%

|

9%

|

|

The Leave Campaign

|

13%

|

25%

|

15%

|

19%

|

|

Political Parties

|

7%

|

6%

|

8%

|

5%

|

|

Social media

|

33%

|

8%

|

18%

|

13%

|

|

Family

|

27%

|

15%

|

18%

|

19%

|

|

Friends

|

23%

|

12%

|

16%

|

15%

|

|

Colleagues

|

5%

|

2%

|

5%

|

3%

|

|

None of the above

|

11%

|

20%

|

16%

|

20%

|

|

Don’t Know

|

10%

|

3%

|

6%

|

12%

|

There was a great deal of consensus that the public were faced with a low quality debate, with misleading information on both sides. So the public arguably turned to those they already agreed with for confirmation. Over the course of the campaign, the influence of social media increased, from 10% to 16%. However, there was a particularly stark shift among young people: from 20% in March to 36% in June – while the figure fell to just 8% for over 65s. This raises questions of online echo chambers among certain demographics, and self-reinforcement stymying knowledge of other viewpoints, particularly through social media algorithms which lead to engagement with viewpoints already similar to one’s own. The demographic diversity of information sources is reflected in the demographic variation of final voting intentions.

Another noticeable trend was the growing importance of friends and family as sources of information, as the ‘don’t knows’ and ‘none of the aboves’ declined towards end of the campaign. The number of people citing friends and family as important sources of information rose from 9% to 16% and 13% to 18% respectively, from February to June. Young people’s reliance on people they know rather than traditional information sources is complemented by the declining role of the BBC on their decision – falling for 18-24 year olds from 40% in March to 24% in June; while the impact of family rose from 20%-27% and friends from 13%-23%. Over 65s in particular turned towards friends and family. This finding arguably reflects two things: firstly, voters’ confusion about the various public sources of information, leading them to rely more closely on individuals they trusted; but secondly and more positively, an increasing reliance on real-life deliberation with those around them as the vote neared.

Contact democracy

Unsurprisingly, when the campaign began, 76% of respondents to our poll said that they had not been contacted about the vote. This figure went down considerably to just 16% in the final week before the referendum. However, that means roughly one in six had still had had zero contact about the vote – a level of exclusion that should be unacceptable for any major political campaign, let alone arguably the most significant vote in UK-wide politics for decades.

The conversation did not reach everyone, and some social demographics were predictably less likely to be contacted than others – 19% of C2DE voters hadn’t been contacted by mid-June, compared to 14% of wealthier ABC1 voters (see Figure 7, p22). While this social divide is generally mirrored in wider politics, it is a sign that more needs to be done in referendums to ensure information reaches the electorate comprehensively and without the kind of demographic divides that create feelings of disempowerment, disillusionment, and a sense of distance from the conversation.

Figure 6: Method of contact

|

Feb-24

|

Mar-31

|

Apr-26

|

May-25

|

Jun-17

|

|

I have not been contacted

|

76%

|

58%

|

25%

|

22%

|

16%

|

|

Telephone

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

3%

|

|

Leaflet or Letter

|

7%

|

25%

|

63%

|

68%

|

72%

|

|

A visit to your home

|

0%

|

1%

|

2%

|

2%

|

2%

|

|

Approached in the street

|

1%

|

3%

|

3%

|

6%

|

8%

|

|

Email

|

4%

|

6%

|

9%

|

10%

|

14%

|

|

Twitter

|

1%

|

1%

|

2%

|

4%

|

6%

|

|

Facebook

|

4%

|

5%

|

10%

|

13%

|

16%

|

|

Other social media

|

3%

|

2%

|

6%

|

6%

|

9%

|

|

Text message

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

1%

|

2%

|

|

Other ways

|

3%

|

2%

|

3%

|

3%

|

4%

|

|

Don’t know

|

8%

|

9%

|

5%

|

4%

|

4%

|

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society. Question: Could you indicate which of the following ways you have been contacted about the EU referendum, if at all?

The government mail-out

The most notable rise in the number who were contacted came in our April poll, the first after the UK government’s national pro-EU mailout which went to 27 million households. This was widely noticed, with the number saying that they received a leaflet rising from just 25% in March to 63% in the weeks following the mailout.

However, the percentage of people who said that the Government were the most important source of information when making up their mind on the EU referendum rose by just two percentage points, from 8% to 10%, between the end of March and the end of April after the leaflet was sent out (see Figure 6). Our polling also found that the percentage of people who said they felt well or very well informed about the referendum actually fell from 23% at the end of March to 21% at the end of April (see Figure 2, p14), two weeks after the mail-out sent on the 11th April. Something clearly went wrong. This suggests that static information sources – and in this case a one-sided publication – had little effect on people’s levels of informedness.

Leaflets in general appeared to have been targeted mainly at older voters, with 83% of 65+ receiving a leaflet by mid-June, compared to 65% of 18-24 year olds. Two potential explanations present themselves. One is that campaigns targeted older voters believing them to be more receptive to the static messaging provided by leaflets. The other is that younger people are harder to ‘reach’ with leaflets than older people, with more young voters living in blocks of hard-to-access flats or with large numbers of other people. That would suggest unequal access to printed materials.

The ground campaign

There was a marked lack of ‘real conversations’ between the campaigns and the voters – genuine two-way discussions that offered proper deliberation. In June, just 2% of people had had someone come to their house regarding the campaign, barely any change on March’s figure of 1%. Equally only 3% of people had received a phone call about the referendum, while 8% had been approached in the street. This suggests most of the information people received was largely one-directional, with no sense of dynamic two-way debate involved, and again reflected the need for two-directional resources and opportunities for in-person and informed dialogue about the issues.

It is also worth noting the differences between England and Scotland (though we should be wary of a particularly small sub-sample in Scotland). Scottish respondents to our polls repeatedly stated they’d had lower levels of contact than English respondents. Whether this reflects lower campaign efforts north of the border is hard to know, but it may be reflected in the lower turnout Scotland had on the day. It is also arguably indicative of wider analysis that the conversation failed to reach and inspire Scottish voters. While the anti-establishment vote in England went wholeheartedly behind Brexit, in Scotland those voters had already largely aligned themselves with Scottish independence and the SNP. Cues from the SNP and indeed the wider Yes movement suggested that a vote to ‘Remain’ might help the case for Scottish Independence. This may have encouraged some of those who wanted to vote Leave to stay at home instead.

Figure 7: Contact by age, social class and region

|

|

I have not been contacted |

Telephone |

Leaflet or Letter |

A visit to your home |

Approached in the street |

Email |

Twitter |

Facebook |

Other social media

|

Text Message |

Other ways

|

Don’t know

|

|

Feb

|

18-24

|

68%

|

0%

|

5%

|

1%

|

0%

|

5%

|

4%

|

8%

|

5%

|

1%

|

7%

|

12%

|

|

65+

|

77%

|

0%

|

10%

|

0%

|

0%

|

7%

|

1%

|

2%

|

2%

|

1%

|

3%

|

2%

|

|

ABC1

|

79%

|

1%

|

7%

|

0%

|

1%

|

4%

|

2%

|

4%

|

2%

|

1%

|

3%

|

5%

|

|

C2DE

|

72%

|

1%

|

7%

|

1%

|

1%

|

4%

|

1%

|

5%

|

4%

|

0%

|

3%

|

11%

|

|

England

|

75%

|

1%

|

7%

|

0%

|

0%

|

4%

|

2%

|

4%

|

3%

|

1%

|

3%

|

8%

|

|

Scotland

|

83%

|

1%

|

6%

|

1%

|

1%

|

5%

|

2%

|

6%

|

3%

|

1%

|

1%

|

5%

|

|

June

|

18-24

|

13%

|

5%

|

65%

|

6%

|

19%

|

17%

|

20%

|

34%

|

22%

|

1%

|

5%

|

8%

|

|

65+

|

13%

|

3%

|

83%

|

2%

|

8%

|

18%

|

0%

|

10%

|

4%

|

3%

|

3%

|

0%

|

|

ABC1

|

14%

|

3%

|

78%

|

3%

|

10%

|

16%

|

7%

|

16%

|

9%

|

2%

|

4%

|

3%

|

|

C2DE

|

19%

|

3%

|

66%

|

2%

|

6%

|

12%

|

4%

|

16%

|

8%

|

2%

|

4%

|

6%

|

|

England

|

16%

|

3%

|

73%

|

2%

|

8%

|

14%

|

6%

|

17%

|

8%

|

2%

|

4%

|

|

|

Scotland

|

18%

|

3%

|

61%

|

2%

|

7%

|

13%

|

5%

|

11%

|

5%

|

1%

|

2%

|

|

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society

The great contradiction: low knowledge, high interest

We believe this analysis reflects an unfulfilled desire for two things: firstly, better sources of information (whether from official, non-partisan, campaign or media sources); and secondly, a genuinely vibrant and ‘in real life’ referendum debate – not just one-sided leaflets, but conversations in communities, colleges and workplaces across the UK about this crucial issue, as witnessed during the Scottish referendum. There was no shortage of interest in the referendum, but there was a huge shortage of people feeling they were well informed about the issues. But those two desires – better information and better deliberation – ought to go hand in hand. The fact that people gradually felt better informed as the campaign went on, and that more people relied on friends and family for information in the final months of the campaign, shows how a longer campaign can start to offer the sort of referendum experience people are after.

Our recommendations (see pp 9-10) are in part designed to increase the likelihood that better information and better deliberation take place as and when referendums occur. The next chapter zeros in on some of the most common complaints made about the Remain and Leave campaigns, adding further weight to our recommendations for better information and better deliberation.

Bad Campaigns

Positivity and Negativity

In this chapter we examine two key aspects of the content of the referendum campaigns themselves. These are the relative degrees of positivity and negativity of each side of the argument, and the use of personalities as campaign tools.

We have focused on these aspects as these are the areas for which we have our own data. But our overall analysis sits within a wider set of concerns about the conduct of the campaigns. In particular, many people simply did not trust the veracity of certain claims made by both sides. In the case of Remain, many were doubtful about a Treasury-sourced claim that households would be on average £4,300 a year worse off out of the EU; on the Leave side, the much-touted £350 million a week which the UK supposedly sent to Brussels provoked significant outrage. Towards the end of the campaign, nearly half of all voters (46%) thought politicians from both sides were ‘mostly telling lies’ versus just 19% who thought they were mostly telling the truth. And both sides were seen to be at fault: 47% thought Remain politicians were mostly lying, while 46% thought the same of Leave politicians.

Our analysis of negativity and the use of personalities adds to this context of deep mistrust of the campaigns. For referendums to be better in the future, it is crucial that this dynamic is changed. That takes action from all sides, including government, campaigns, media and indeed citizens themselves. Our recommendations (see pp 9-10) are designed as first steps towards taking the action needed to end the culture of fear and loathing that can surround referendum campaigns.

A negative campaign

There is considerable consensus that the EU referendum campaign was a highly negative one. From accusations of a ‘Project Fear’ being run by the Remain camp, to controversies over UKIP’s ‘Breaking Point’ anti-immigration poster, it often felt like a positive vision for Britain’s future in or out of the EU was sorely lacking – evidenced by the fact that for every positive word in media headlines there were more than two negative ones.

This was in large part reflected in the content being put out by the separate camps. The focus on the economy and immigration in the debate was largely framed negatively – with Leave focusing on the pressure of immigrants on public services, while Remain warned of economic turmoil in the event of a Leave vote. As the University of Copenhagen’s Charlotte Galpin noted, Remain’s “predictions…included a cost of £4,300 a year for every household, a wage drop of £38 a week, the loss of 100,000 manufacturing jobs, a 10-18% drop in house prices and higher mortgage rates, two more years of austerity, an increase of £230 on the average family holiday, loss of women’s rights, an ‘instant DIY recession’ and 500,000 more unemployed, amongst others” while Leave were criticised for their claims about potential mass immigration from Turkey and divisive comments from Nigel Farage (on sex attacks) and Boris Johnson (making insinuating comparisons about the EU’s goals and Nazism).

Emotions play a strong role in any political debate. However, excessive reliance on them, particularly negative emotions, can have a stifling impact on informed debate: “They…risk inhibiting critical engagement and reflection. Fear is used to prevent citizens from evaluating the facts, weighing up the evidence, thinking about the issues,” while reinforcing political cynicism, notes Galpin.

There was significant variation in the levels of negativity among the campaigns, but the following breakdown looks at one week in February – arguably before much of the negativity intensified. The following graph is a breakdown of tweets from each group and each camp, measured by their tone, for the week to the end of 17th February:

Figure 8: How groups frame arguments, themselves and each other

Source: Simon Usherwood and Katherine Wright

It shows that there was significant negative framing from Vote Leave, StrongerIn, Leave.EU and Conservatives for Britain, some of the leading groups on each side. Some argue this contrasts with the Scottish referendum, where ‘Project Fear’ was more one-sided; in the EU debate, ‘both sides… engaged in their own brands of scaremongering and… failed to put any real positive vision forward to their viewpoint be it Remain or Leave’. While social media was mostly positive, at least in the early stage of the referendum, wider messaging appeared to reflect a discourse of ‘risk’.

There was always going to be a tendency for the campaigns to focus on risk. That is because ‘people are on average three times more motivated by aversion to risk than by opportunities for gain’. However, negative campaigning ‘only works if the public believes it and does not see it as being deliberately manipulative’. In a debate that had – even before the referendum – been strongly driven by emotion and feelings of identity, and where there are few clear facts or certain predictions about the future, there was a natural drive towards stimulating these strong sentiments over evidence.

While there is a clear role for robust debate and challenging competitors’ claims, at times this negativity was doubtless a turnoff for members of the public. When we first polled whether the Remain campaign was positive or negative, most respondents said they did not know (see Figure 9). But as the campaign wore on, the view that the Remain campaign was negative escalated. By the final week before the vote, 51% of respondents felt that the Remain campaign was negative, as opposed to only 9% who thought it was positive.

Figure 9:

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society

The pattern for the Leave campaign is different, in that both positive and negative views of the campaign grew. Nonetheless, by April, the plurality view was, once again, of a negative campaign, with 39% stating this view. However, 31% of respondents did view the Leave campaign as positive, showing opinion was divided, including in part along voting lines. In our final poll, only 12% of Remain voters described the Leave campaign as positive, as opposed to 52% of Leave voters.

Figure 10:

Source: BMG/Electoral Reform Society

The clear lesson from this data is that as the campaigns wore on, they were seen to increase in negativity. While evidence is mixed as to the impact of negative campaigning, most people are in agreement that having a positive vision should be a key part of any campaign. Negative campaigns tend to reinforce a focus on risk and fear, rather than inspiring voters. A recent study showed that ‘positive campaigning is more likely to garner… a larger number of voters, and said voters will also be more trusting of and optimistic about the [side] they choose to support due to the positivity of [the] campaign.’ This suggests that negativity plays an important role in fostering the culture of mistrust which was so in evidence throughout the EU referendum campaign. Positive campaigning – always within the context of robust debate – should therefore be encouraged.

Much work is required to ensure that in future the tone of the debate is one which is positive enough to facilitate the most reasoned and deliberative debate possible. Too often, negative campaigning can descend into personality-based mudslinging, and when that happens, voters are short-changed and deprived of the really powerful, issues-based conversation they deserve.

'Big Beasts'

Figure 11: Effect of personalities on voting intention, June 17th

BMG/Electoral Reform Society. Question: “Has the contribution from the following people to the EU referendum debate made you more or less likely to vote for either side?

According to our polling, the effect of big personalities on voters’ intentions was surprisingly minimal. Most respondents did not claim to be affected by any of the personalities mentioned, suggesting that the value of personality-driven campaigning is limited. Notably, the numbers saying they had been made more likely to vote Leave by every personality was higher than those who said they were likelier to vote Remain because of them. This may represent a large number of voters determined to demonstrate their Leave credentials no matter what, or a rebellion against some of the more ‘establishment’ personalities mentioned (such as David Cameron). A particularly low figure for Alan Johnson may be a result of the Labour In campaigner’s relatively low profile during the campaign. That Nigel Farage is the personality who scored the highest ‘makes me likelier to vote Remain’ score (at 20%) also hints towards the polarising aspect of his profile, with many of those saying this likely to be motivated by a desire to demonstrate their dislike for Farage.

The only personalities who appeared to have the desired effect on their audience were Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Donald Trump – all of them arraigned on the ‘Leave’ side. The anti-establishment aspect of the Leave vote (demonstrated by the increased likelihood of voting Leave after listening to Remain-supporting ‘establishment’ figures) might have been strengthened by the markedly anti-establishment political styles of all three of these politicians.

Above all, what these numbers tell us is that people had by and large lost faith in established political figures as opinion-leaders – except where those figures might be said to be kicking against the establishment. Traditional theory on campaigning in referendums is that such figures can command considerable allegiance owing to voters’ tendency to follow political party cues. But such was the culture of mistrust in the EU referendum that the ‘big beast’ approach appeared to have, for the Remain side at least, the opposite of the desired effect.

The failure of personalities to ‘cut through’ should not necessarily be seen as an entirely bad thing. While this culture of mistrust is ultimately corrosive for our politics, members of the public ought to be healthily sceptical about the claims and counter-claims made by campaigners. In an environment where people felt better informed about the issues and were able to have real, meaningful, deliberative discussions with those around them, a lack of ‘blind faith’ in leading politicians would be much more positive. But in the case of the EU referendum, a potent cocktail of low levels of information, high levels of mistrust and considerable negativity from the campaigns created an atmosphere that few would consider an example of good democracy in action.

In the next chapter we explore an alternative model of doing politics. We have talked a lot about deliberation – but what does it mean, and what would a more deliberative referendum campaign actually entail?

Talk it Out

Deepening public involvement

As we have seen, the EU campaign was often perceived to be dominated by personality politics, party spats and contradictory statistics, and failed to inspire or properly inform the public. At the ERS, we are committed to deeper public involvement in our democracy. We believe everyone should feel equipped to take part in politics, and every voice should be heard and valued. That often means finding new ways and offering new platforms to bring people into political discussion. And that is what we did during the EU referendum.

A 'Better Referendum'

In May 2016 the Electoral Reform Society, in collaboration with the Crick Centre for the Understanding of Politics (University of Sheffield), the Centre of the Study of Democracy (University of Westminster), and the Centre for Citizenship, Globalisation and Governance (University of Southampton), with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust (JRRT) launched an online toolkit to create a more informed EU referendum debate.

A Better Referendum was a free online resource on the EU referendum with contributions from senior figures in both official campaigns, and from leading EU experts from across the UK (drawn from the UK in a Changing Europe programme). The goal was to give citizens a chance to discuss the issues with each other, to debate them and learn from each other. We tried to help to widen the democratic space around the EU referendum.

The project created a mechanism by which citizens were able to access authoritative and independent research on the UK’s relationship with the EU in an accessible and interactive format. The tool was designed in such a way to enable people to discuss what they felt was most important in the referendum and, crucially, what they felt to be missing from the debate.

In their own meet-ups, voters picked the issues they wanted to discuss with the time they had available, and the site took them through the facts with the academics, and then the arguments of both campaigns, with time for discussion and deliberation (and tea). The aim was to create a platform for informed and vibrant deliberation. A Better Referendum gave citizens the information and arguments on the issues they wanted to discuss – picking from Social Policy, Migration and Work, Crime and Security, Regions and Nations, and Economic Impact – and then the time to come to their own conclusions in discussion with each other.

While the project had limited takeup – with around 500 people attending events which used the online tool (see map, page 37, for locations of some of these events) – our survey of users showed that the tool had the desired effect. All respondents said they were able to make a more informed decision in the referendum as a result of using the tool (although very few said they had changed their mind about which way they were going to vote). And the website which hosted the videos and other materials associated with the tool had over 12,000 unique visitors – many of whom were there to access both the independent academic video content and the partisan content from both campaigns.

The project was inspired by the deliberation in evidence in and around the Scottish referendum of 2014. Despite similar problems with negativity as those described above (see pp 25-29), the campaign in Scotland was given enough time to bed in with the electorate. Partly as a result, the scale of deliberation among friends, family and community groups was much greater (see page 49). A referendum can involve an engaging national conversation that brings in everyone. We wanted to bring some of that spirit to the EU referendum.

The project also built on work by the consortium that hosted Citizens’ Assemblies on local devolution deals in Southampton and Sheffield in late 2015, also funded by the ESRC – with several partners involved in both initiatives. These were experiments in deliberative democracy which demonstrated the public appetite for discussing complex constitutional issues. Randomly selected and broadly representative groups of people got together over two weekends in both locations to talk about the devolution deals on the table and to decide where they wanted powers to lie at the local level. The project tested the idea that citizens are able to take the lead in constitution-making, and found emphatically that they could. In this context, the sort of deliberation encouraged by the Better Referendum project – and the deliberation which we believe should be a key part of all future referendums – is part of a much-needed wider commitment to citizen involvement in our democracy.

It's good to talk

Our Better Referendum project demonstrated the public thirst for informed deliberation about the issues surrounding the European referendum. At its best, the project acted as a guide for how good deliberation can be supported in future referendum campaigns (as well as a warning of some of the challenges and pitfalls of this kind of project).

Many of the recommendations we make for the future conduct of referendums (see pp 9-10) stem from our conviction that there needs to be a greater role for deliberation during referendum campaigns. In the first instance, there needs to be much greater emphasis placed on laying the groundwork for the vote. That means making sure the rules of the referendum are clear and fair enough to minimise controversy, and above all making sure the campaign is long enough for people to have time to deliberate meaningfully about the issues. There then needs to be an ‘information’ phase which seeks to arm voters with basic levels of information and counteract any misinformation emanating from the campaigns. Finally there should be a public effort to support real deliberation by voters and to encourage media outlets to do the same.

The aim is to create an atmosphere which gives people the confidence to engage fully with a referendum campaign for themselves, and to lead discussion about the issues within their communities (both online and off). A richer referendum campaign is one where responsibility for informed debate lies not only in the hands of the official campaigns or traditional media but is shared more widely. By talking with each other about the issues around a referendum, the public can take a leading role in the debate.

Referendums Everywhere

Past Referendums

We now turn to the wider context of referendums in British and wider political history, in order to deepen our understanding of what happened in 2016. How does the EU referendum compare to recent referendums in the UK and to the practice of other countries? We look at some recent examples: for each referendum we examine first the laying of the groundwork – the extent to which the rules and regulations of each vote affected the quality of the referendum; we then look at the quality of information and the effects of the campaign itself on voter experience; and finally we ask to what extent the public were able to deliberate about the issues surrounding the referendum. This analysis provides the basis for making the case for our five recommendations on the future conduct of referendums.

The 2011 AV Referendum

The referendum on the Alternative Vote in 2011 was the last UK-wide referendum in the UK and offered some clear parallels with the EU referendum – but also key differences. UK-wide referendums have been extremely rare historically, leaving few points of comparison to draw firm conclusions. In particular, the different degrees of voter interest and different party-political contexts made for very different events.

Laying the Groundwork

One of the clearest differences about the AV referendum compared to the 2016 EU referendum was that it had a guaranteed, clear outcome: enshrined in the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 was the introduction of a specific voting system. That meant that if the public voted ‘Yes’, the Alternative Vote would have been legally enacted automatically. This was unusual: referendums are habitually only ‘consultative’ in the UK, in that while few governments would dare to ignore the result of a referendum, there is no automatic legal process to enact it. The AV referendum was different. This ensured a certain amount of stability and clarity over the outcome. And that was in contrast to the EU referendum, which did not legislatively commit to a specific result. Implicit was a view that the result would de facto commit the Prime Minister to enact Article 50, however there was no timescale for if/when that should happen.

Moreover, there was no clarity over what form Brexit should take. The question was not ‘Should the UK enact Article 50 and join the European Economic Area’ but was instead a more expansive question on membership of the EU, without discussing the options available given a Leave vote. This meant that there was a considerable degree of ambiguity surrounding post-referendum scenarios.

The AV referendum also coincided with local and devolved elections, which meant that, as with many referendums, the vote was tied up with voters’ perceptions of party performance and desire to punish or reward the government of the day. This was, to an extent, an issue with the EU referendum, where there were significant concerns that the proximity to the elections in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland led to a false conflation of the issues and powers of these governments/administrations and their relationship with the EU, and the feeling that the elections and referendum themselves would each overshadow one another.

Quality of information and campaigning

The issue of electoral reform via the Alternative Vote was an unfamiliar topic to most voters, and levels of ‘informedness’ were low. As we have seen (see pp 13-16), this was mirrored in the EU referendum. But in contrast to the EU referendum, levels of interest in the AV vote were low as well – as shown by the low eventual turnout of 42.2%. This adds to the case for extensive public information and education campaigns before the official campaign period begins, in order to contextualise what are often highly complex issues. It was needed in the EU referendum, and it was doubly needed in the AV referendum. It also raises the question of which issues are appropriate to put to a public vote.

A key issue during the AV campaign was the level of disinformation during the referendum. An internal report commissioned by the Electoral Reform Society (which strongly supported the Yes to AV campaign) concluded that ‘manifest falsehoods were allowed to stand largely unchallenged’. Again, this was mirrored in the EU referendum, suggesting that there needs to be a serious examination of what can be done to regulate campaign messages during referendums.

Media coverage also understandably plays a significant role in any campaign. In both the AV and EU referendums, coverage focused largely on the partisan implications and disputes, making it often feel more like a ‘Westminster parlour game’ than a real debate on the issues. In the AV referendum, this centred around the Liberal Democrats’ role in government as the coalition partner, while in the EU referendum it centred on fissures within the Conservative party. Many journalists present referendums through the lens of everyday party politics – as evidenced by the emphasis on ‘Boris v Dave’ and the implications of the referendum for the future leadership of the Conservative party.

Extent of Deliberation

The low levels of information and interest about the AV referendum meant that there were few reports of real, meaningful deliberation taking place. This may have been affected by the short timescale for the vote. The Act was passed in mid-February 2011, and the vote was in May – leaving voters less than three months to get to grips with the issues surrounding voting reform.

Welsh devolution referendum 2011

In 2011, the Welsh people were asked to vote on whether to introduce greater devolution. They voted for devolution, but on a low turnout of 35%. This referendum was above all a demonstration of how plebiscites are often used more to manage internal party politics than to obtain a popular mandate.

Laying the groundwork

The 2011 referendum was not on a fundamental constitutional issue, since devolution as a principle had already been won in 1997. This follows a pattern that, due to a lack of a clear British doctrine on referendums and when it is appropriate to call one, they are often less based around fundamental constitutional change than political priorities. In Wales’s case, Labour’s internal divisions on devolution have driven the constitutional process. The 2011 referendum occurred due to the need for then Secretary of State Peter Hain to find compromise between the different wings of his party in his revision of the Government of Wales Act in 2006. He also needed to manage inter-party relations with Plaid Cymru following the ‘One Wales’ Labour-Plaid coalition following the 2007 Assembly election.

One of the potential explanations for the low turnout was the complexity of the question being put to the Welsh people. This may have combined with the low saliency of the issue given the fact that the principle of devolution had been decided in 1997. This again raises the question of which issues should be put to referendum. However, polling throughout the campaign showed that the best predictor of how people voted was not class, identity or language but ‘constitutional preference’. This suggests that despite all the problems of the referendum’s salience and complexity, the fact that the ‘starting gun’ for the campaign was effectively fired in 2007 (four years before the vote) meant that voters had time to understand the question in terms of its real constitutional significance rather than proxy factors. Although turnout was disappointing, those who did vote appeared to do so from a relatively well informed position, and the polling suggests that differential turnout did not significantly affect the result

Quality of information and campaigning

A notable feature of the 2011 referendum was the All Wales Convention (AWC) touring the country to educate the public on the options available. While there were some political tensions surrounding this initiative, and its degree of success and reach was questioned, it did provide a relatively impartial voice in the debate and its work was covered by Welsh media. The AWC’s initiative was in part a direct response to well-documented weakness in Welsh media and the coverage of Welsh issues at UK level. Polls consistently showed a very large growth in support for devolution since 1997 but also showed high levels of confusion on which powers already resided in Cardiff Bay. There was therefore a real fear that the 2011 vote was based on low levels of information (and could therefore be damaging to the devolution process).

Extent of deliberation

The 2011 Welsh Devolution Referendum featured some elements of deliberation, with the AWC being set up before it was even certain a referendum would be held. However, the AWC was largely perceived as a top-down affair, rather than a citizen-led initiative. Run by government appointees, it was not the citizens’ assembly-style process which the ERS trialled during the EU referendum vote (see chapter 3). Its remit however was positive – to raise awareness and understanding of constitutional arrangements, to hold a participatory consultation, and to inform the Welsh government of the public’s views.

The AWC held formal public meetings and evidence sessions as well as a more informal process of “talking to people in supermarkets…visiting schools, going on road shows, [and] attending community events”, with public deliberative events drawing between 60 and 150 people each. The AWC therefore played an important role in building the public’s understanding of the Welsh constitutional context.

However, the AWC would always be limited by its lack of direct involvement of citizens in terms of setting the agenda – with its role constrained by a top-down process of informing rather than fostering deliberative debate. Moreover, events often attracted only those who already felt most strongly about the devolution issue. A deliberative democratic process alongside a referendum would seek to draw in as many ‘non-political’ or undecided people as possible.

Scottish Independence Referendum, 2014

While the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, like all referendums, had party political origins, it was also unarguably held to answer a question of fundamental constitutional significance. The levels of registration, turnout and deliberation were unprecedented in recent UK political history. And while it is clear that the referendum has not settled the question of independence – and not everything about it was positive – it has had some strongly beneficial effects in terms of democratic participation.

Laying the groundwork

The referendum was held thanks to the SNP’s achievement of a majority in the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, rather than a surge in support for independence. While independence motivates many of the SNP’s core voters and activists, the party’s electoral success was mainly down to its perceived competence as a minority government over the previous four years. So even this highly significant and popular referendum cannot be said to have emerged from the grassroots.

The responsibility for setting the referendum question was given to the Scottish Parliament, but the wording was reviewed by the Electoral Commission. The Commission found that the wording of the original question, “Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?”, was leading, and suggested it be replaced with “Should Scotland be an independent country?”. This suggestion was accepted by the Scottish Parliament.

The Scottish Government, with the support of Scottish Labour, the Scottish Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Greens, legislated to ensure that 16-18 year olds were allowed to vote in the referendum, in line with SNP policy. While this was criticised by some as an effort to skew the result towards ‘Yes’, the referendum result showed no obvious preference for independence amongst that age demographic.

Quality of information and campaigning

The ‘Yes Scotland’ and ‘Better Together’ campaigns were launched in May and June of 2012 respectively. It had been as good as certain since the SNP’s election win in 2011 that there would be a referendum in the second half of the parliament, as pledged by Alex Salmond before the election. This meant that there was effectively three years between the knowledge that the vote would happen and the vote itself, allowing for an extensive period of campaigning, both formal and informal.

The referendum was characterised by a wide variety of forms of engagement, from new media like Wings Over Scotland and National Collective, to new organisations of activists like the Radical Independence Campaign. Social media had a particularly prominent but controversial role, with the widespread use of hashtags, memes, short videos and infographics to spread messages from both campaigns. However, there was some degree of frustration with the at times hostile environment online as well as the tendency for social media to become an echo chamber. In the physical world, there were many small local groups operating with considerable autonomy from the official campaigns. These coordinated door-knocking and phone canvassing activites, as well as well-attended town hall and community meetings across the country.

There was a particularly marked contrast with the EU referendum in terms of the information and detail produced on the impact and results of a vote for change. The Scottish Government produced a large document (‘Scotland’s Future’) detailing its plans for an independent Scotland and the specific process it expected to follow in becoming independent.

A study conducted by the Electoral Commission after the referendum found that 90% felt they knew a great deal/fair amount about what the referendum was on. And 59% said they found it easy to find information on what would happen in the event of a ‘Yes’ vote, and 64% for a ‘No’.

Approximately 89% of 16-17 year olds resident in Scotland were registered to vote by the day of the referendum, and the campaign saw a high degree of prominent engagement from young people, particularly through social media and in many of the new campaign organisations.

The vote itself saw a turnout of 84.6%, the highest recorded for any election or referendum in the United Kingdom since the introduction of universal suffrage. The Electoral Commission found that “more than in previous elections, people appear to have voted in the referendum because they believed they could influence the result”.

Extent of deliberation

During the independence referendum Scotland became a relative hotbed of deliberative political spaces, with citizen-led town hall meetings springing up around the country. While many of these tended to be partisan, organised by campaigners for one side or the other, there were also several events which sought to elevate deliberation above the constitutional binary. Our own Democracy Max project brought together citizens, experts and policymakers for a series of events to design a Scottish democracy fit for the 21st century, regardless of the referendum result. The participatory democracy group So Say Scotland and the ACOSVO and ESRC-funded Future of the UK and Scotland event sought to achieve similar things, and many other similar groups and events during the referendum have left a legacy of experimentation with deliberative forms that can be drawn on for years to come.

Referendums around the world

Referendums are in common use around the world. So far in 2016 IFES holds records of nine national-scale referendums held around the world, with a further four scheduled . According to the political scientist David Altman, twice as many referendums were held in 2009 as 50 years previously.

Referendums appear to be becoming increasingly common not just in the UK, but across Western democracies, undoubtedly an effect of increasing tensions within representative democracy. Technology also makes referendums easier, with more direct broadcasting of views now possible between citizens and the centre. The growth of single issue politics also lends itself to direct democracy. The referendum, then, appears to be here to stay.

Laying the groundwork

One notable difference between the UK and the rest of the world is the process of calling referendums. In the UK, referendums are called by Parliament. The subject matter and regulation of referendums is entirely in the hands of the British Government and Parliament (although there are roles for pre-existing statute such as the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act as well as official bodies such as the Electoral Commission, these can be subject to change by parliamentary vote) or Scottish and Welsh administrations for issues relating to those countries specficially. By contrast, in many US states as well as New Zealand, Switzerland, Italy, and the Netherlands, referendums can be held on the basis of signatures from members of the public.

But such a process can be victim to abuse. In Switzerland, the four largest parties are almost always in power together partially because a sizeable opposition party could just deluge the government with referendums. In California an entire industry has emerged of petition collection companies who charge special interests for signatures.

There are also questions about the effects of this type of direct democracy on the quality of democracy and governance. It is not necessarily the case that citizen initiated referendums result in a stronger democracy, if a deluge of referendums causes voters to become confused or indifferent. Concurrent referendums can result in one issue clouding others.

Yet there are also problems around referendums being events decided entirely by governments. As in the UK, this can mean referendums used as tools for managing internal or inter-party disputes rather than as a means of gaining a real popular mandate for an issue of major constitutional importance.

Laying the groundwork

One notable difference between the UK and the rest of the world is the process of calling referendums. In the UK, referendums are called by Parliament. The subject matter and regulation of referendums is entirely in the hands of the British Government and Parliament (although there are roles for pre-existing statute such as the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act as well as official bodies such as the Electoral Commission, these can be subject to change by parliamentary vote) or Scottish and Welsh administrations for issues relating to those countries specficially. By contrast, in many US states as well as New Zealand, Switzerland, Italy, and the Netherlands, referendums can be held on the basis of signatures from members of the public.

But such a process can be victim to abuse. In Switzerland, the four largest parties are almost always in power together partially because a sizeable opposition party could just deluge the government with referendums. In California an entire industry has emerged of petition collection companies who charge special interests for signatures.

There are also questions about the effects of this type of direct democracy on the quality of democracy and governance. It is not necessarily the case that citizen initiated referendums result in a stronger democracy, if a deluge of referendums causes voters to become confused or indifferent. Concurrent referendums can result in one issue clouding others.

Yet there are also problems around referendums being events decided entirely by governments. As in the UK, this can mean referendums used as tools for managing internal or inter-party disputes rather than as a means of gaining a real popular mandate for an issue of major constitutional importance.

Quality of information and campaigning

A question of some controversy during the referendum campaign was whether the campaigns were misleading the public in their statements or advertising.

In the UK, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) cannot rule on political advertising. However, equivalent bodies elsewhere do not have such stipulations. During the 2008 election in New Zealand their ASA ruled against advertising by campaigns in three cases.

However, it is worth recognising that the nature of political campaigns means that very few statements can be determined as out-and-out lies. Usually there are questions of interpretation or speculation that can raise enough doubt to make a clear ruling difficult. This makes such rules politically sensitive and difficult, as well as a potential freedom of speech issue. The UK ASA’s own argument is that it would be “inappropriate” for such a body to intervene. But given the scale of concern about misleading claims, particularly in referendum campaigns, it may be appropriate to invest the Electoral Commission or a specially convened referendum commission with powers of intervention.

Extent of deliberation

In recent years there has been an increased role for citizens’ assemblies. Assemblies of randomly selected citizens have been used in Canadian provinces, Ireland and other states to deliberate on constitutional issues. In Iceland a directly elected assembly was used, though it was nonpartisan in nature.

While these assemblies were charged with deliberating on major constitutional issues, a ratification process was still required. In the Canadian and Irish cases, referendums were written in from the start, whereas the Icelandic convention chose to call a vote on six areas of their deliberations.

This process of formal deliberation offers an environment more conducive to a good referendum campaign, as the issues are teased out before the referendum. The deliberative nature of this process also means that the structure and subject of a referendum will be less politicised and have more direct legitimacy with the public. In several cases members of citizens’ assemblies have become public advocates for their recommendations. The process of citizens’ assemblies can create an alternative source of expertise, with members of such assemblies offering a fresh perspective on the topic through the process of deliberation.

Similarly, the process of Swiss referendums is more consensual than it might first appear. When citizens launch a referendum, the legislature has the capability to launch a counter proposal. A process of negotiation between initiative committees and the authorities thus quietly begins and often the initiative committee accepts an alternative proposal.

Is there another way?

The recent history of referendums in the UK and around the world shows that there is no one set way of doing things. All approaches have their benefits and their drawbacks. One of the clear lessons is that the salience of an issue is crucial for the success of the referendum. The question of Scottish independence was always going to ignite the passions of voters. And where the salience is less obvious, real efforts at informing voters can pay dividends – as in the Wales 2011 referendum. But another lesson is that referendums tend not to settle a question. In none of the cases discussed above have the issues around any given referendum question gone away. Given the frequency of party-political imperatives behind the calling of referendums, it is worth asking: what are the conditions where a referendum is really the best way of settling a political question? Perhaps parties and politicians should make a habit of reflecting on some of the difficulties around calling and then responding to referendums, and – where possible – seek to find a way through the thicket of representative democracy instead.

Conclusion

It's good to talk