140 Years of the ERS

A historic document

In 1984, the Electoral Reform Society commissioned a history of the Society’s first 100 years. Now, 40 years later, I’m pleased that we can make it publicly available once again to celebrate our 140th birthday.

This is a historic document, reproduced in its entirety. If you are interested in the history of the Society, the earliest records are held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick.

Darren Hughes

Chief Executive

16 January 2024

Foreword by Dame Margery Corbett Ashby

Born shortly before the Society, died 1981

As a devoted advocate of electoral reform all my political life, I have great pleasure in recording my admiration for the gallant way in which this society (only two years my junior) has consistently battled for a truly democratic electoral reform. I wish to pay tribute to my colleagues who continue to work against the apathy of the political parties that short sightedly prefer party power to democracy. I admire the way in which our society can make new forms of voting intelligible to the electors. Personally, I believe our voters are as intelligent as those in the many stable states in Europe and elsewhere. Electoral reform can prevent a slide to personal tyranny or to that of communism. At 95 I cannot wait long for the success of our cause, but I do not believe that our country will long remain content with the in-out, in-out, of our present system. It will look to freedom of expression resulting in a consensus of opinion, arising from freer voting, grouping and regrouping of informed opinion on matters arising in parliament.

Best wishes and warm admiration for our courageous and devoted leaders.

Margery Corbett Ashby

(Dame Margery wrote this Foreword for the Society in 1977 in anticipation that a record of its achievements would be compiled for its centenary.)

Thomas Hare, Lord Avebury & Lord Courtney

Thomas Hare, Lord Avebury & Lord Courtney

100 Years of the Electoral Reform Society

Reform in the Air

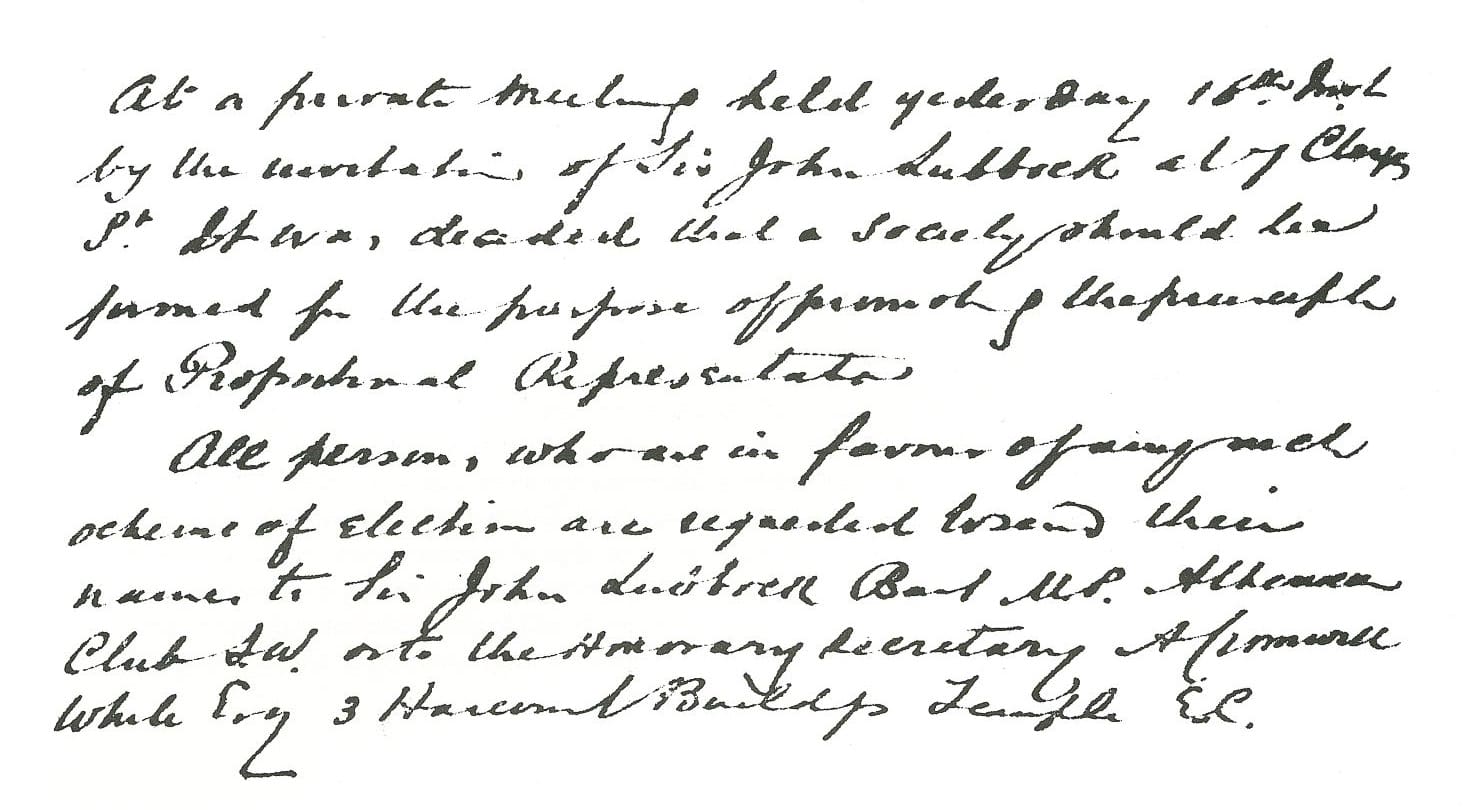

On 16 January 1884 a private meeting convened by Sir John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury) decided to form a society for the promotion of proportional representation; this was made formal by a general meeting on 5 March.

In the seven weeks between those two dates, a great deal of work was done, including press publicity, personal approaches to likely supporters and even, at a meeting, a mock election by the Single Transferable Vote system (STV). From the beginning, the society exhibited the features it still retains. It was all-party, its early members including 43 Conservative and 38 Liberal MPs and ‘nearly all the moderate Home Rulers’. It maintained close contact with interested people in other countries, one of its earliest letters being to the president of the Association Réformiste in Geneva. While the main emphasis was on parliament (especially in view of Franchise and Redistribution Bills then being debated), it was recognised that reform should extend to local government and other elections. The first general meeting passed a resolution calling for ‘some form of proportional representation’, but the third meeting, nine months-later, adopted a report by its committee, which ‘after very carefully considering all the different systems of voting’ proposed to it, ‘had come to the conclusion that the single transferable vote on Mr. Hare’s plan was, on the whole, the best system that could be adopted’. An advantage of PR that was stressed from a very early stage was ‘maintenance of the individual community’ as against the division of natural communities which single-member constituencies entail.

Pressure for the reform worked out by Thomas Hare had in fact begun much earlier, involving besides Hare himself John Stuart Mill, Henry and Millicent Fawcett and other leading figures of their time. They had formed the Representative Reform Association which published a valuable report and some of whose members became founder members of the new society. Those founders included, besides Sir John Lubbock, at least two whose names still mean something to our later generation – Albert Grey, later Earl Grey, and C.P. Scott. Also Walter Morrison, who in 1872 unsuccessfully introduced a bill for the single transferable vote in parliamentary elections, and whose great grand nephew is a leading member of Conservative Action for Electoral Reform. James (later Speaker) Lowther was a founder member and Lord Birkenhead made powerful speeches in favour of PR, as did Thomas Burt the miners’ leader.

The stimulus for the formation of the new society seems to have been the imminence in 1884 of two parliamentary bills which offered a chance of reform by means of amendments, one bill greatly extending the franchise and the other bringing about a drastic redistribution which for the first time established the single-member constituency as the norm.

Preparations for these involved a great deal of activity. The society’s press cutting books contain hundreds of letters to national and provincial papers and reports of meetings in all parts of the country. Demonstration STV elections were a very early feature and one had school children as the voters, who experienced no difficulty. Grey also carried out in his constituency a real election among miners choosing their agents. It is noteworthy that one argument used against the existing system was the danger in Ireland of inflaming communal strife by depriving the minority of its due voice in parliament. It had been hoped that the government would incorporate in its bills a measure of proportional representation. When it refused to do so, Leonard Courtney (later Lord Courtney) resigned his ministerial office and joined the Society, serving as Chairman of its Committee until his death in 1918.

The subject was raised in speeches on the first bill, pointing out the injustice and the danger of increasing by more than half the number of people entitled to vote if there was no guarantee that their votes would have any effect on the result. Amendment to secure a better system was, however, left to the bill on redistribution.

Early Resistance

In the second reading debate on that bill, Leonard Courtney, a few days after his resignation as financial secretary to the treasury, attacked the single-member constituency, and later Sir John Lubbock, President of the Society, moved an amendment which would have made the vote transferable. However, government and opposition leaders had committed themselves to the redistribution scheme as it stood, and Sir John’s motion was defeated by 31 votes to 134.

Although the reformers never thought of that defeat as more than a temporary setback, they saw no prospect of reopening the matter in the near future, and therefore decided to vacate the Society’s office in Palace Chambers, maintaining a secretary, Miss Orme, to deal with enquiries. Its first annual report listed 25 publications, many of them reprints of speeches or newspaper articles, so there must have been material available to those interested.

There was also considerable activity by leading members of the Society, seizing opportunities as they arose. Among the more important events was a deputation to the prime minister and the president of the Local Government Board in 1888, urging the election of the new county councils by the single transferable vote. However, Lord Salisbury professed himself precluded from expressing an opinion on the deputation’s case because the terms of the bill were awaiting final sanction by his cabinet. An important meeting was held at the home of Thomas Hare’s daughter, Mrs. Westlake, on 10 July 1894, when the principal speaker was Catherine Helen Spence, one of the foremost pioneers of electoral reform, who spoke from the experience of thirty years’ campaigning in Australia. Numerous articles and pamphlets appeared. 38 years later, after Miss Spence’s death, the Society welcomed a similar visit by her successor in South Australia, Mrs. Jeanne F. Young. Close links with Australian reformers have always been maintained, recent visitors to Chancel Street being Jack and Kate Wright, Christopher Harte, John Campbell and Deane Crabb. J.F.H. Wright is the first President of the Proportional Representation Society of Australia and author of Mirror of the Nation’s Mind.

Enter Humphreys

John H Humphreys

John H Humphreys

The period of ad hoc activity had lasted until the annual meeting on 10 May 1906, when the grossly distorted result of the general election at the end of 1905 provided a stimulus to a renewal of organised protest. The Liberals were indeed entitled to their victory, having polled more than half the total votes (the only time in the 20th century so far that any one party has achieved this) but for 55% of the votes they had a nearly 2 to I parliamentary majority. Besides this, there was anxiety lest the new Transvaal parliament, inheriting the British electoral system, should suffer from a dangerous exclusion of minority voices.

The meeting was again held at the president’s house, with Leonard Courtney and other stalwarts of 20 years earlier, but the new century brought in new names, among them J. Fischer Williams, Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Hilaire Belloc. Of the most lasting importance was John H. Humphreys, who had become honorary secretary on Miss Orme’s retirement in March 1905 and in serving the cause devotedly for the next forty years was to become recognized as the world’s leading authority on the subject. He was a gentle and persuasive man, of encyclopaedic knowledge.

From 1906 onwards we have regular annual reports and the press cutting books are again kept up to date, showing a large number of meetings addressed. Pamphlets published included Lord Courtney’s speech in moving, in April 1907, the second reading of his Municipal Representation Bill, a permissive measure which would have allowed any municipality to have its council elected by STV if it wished. The select committee to which the bill was referred recommended acceptance of the measure for experimental periods of three years and the bill passed all its stages in the Lords. However, when introduced (twice) in the Commons it encountered the usual difficulties in the way of a private member’s bill and made no progress.

The same period saw a decision to publish a journal, Representation, which appeared at least quarterly from February 1908 until August 1923 and was the ancestor of the Society’s present journal under the same name. It is a mine of information for that period. In 1907 also, the Society again acquired offices, 28 Martin Lane, Cannon Street, which in 1910 it left for the more politically convenient 179 St. Stephen’s House, Westminster.

The next important piece of work was the giving of evidence to the Royal Commission on Electoral Methods, appointed by the government in 1908. This was the result of a resolution passed at the Trade Union Congress and a deputation to the prime minister (Asquith) which included some 40 MPs and others interested in electoral questions. The Commission’s minutes of evidence show what a large part was played by the Society; witnesses included all of its officers and several other members, besides some of its foreign correspondents. The Commission found STV the best proportional system but (Lord Lochee dissenting) did not feel able to recommend its adoption ‘in existing circumstances’ for elections to the House of Commons. It did recommend it for local government and elections not involving parties. The report was a mine of information for the 1917 Speaker’s Conference, and remains valuable. Its conclusions were doubtless influenced by the paucity of experience of STV in actual use. Thirty five years later, in 1953, the Society led a campaign for the appointment of a new Royal Commission to examine the experience accumulated over that time, but the government would not respond. Though it did not achieve the effect most hoped for, the Royal Commission of 1908 did lead to important developments after the first world war.

Trade Unions

This period in the Society’s history saw also the beginnings of what was to develop into a major part of its work and an important source of revenue. The Northumberland miners, who had used the alternative vote to elect their agents in 1885, continued this practice and it extended to the new federation, the National Union of Mineworkers. The NUM called on the Society for assistance in the impartial counting of votes. The National Insurance Acts of 1910 brought in another client – the National Union of Railwaymen’s Approved Society, set up to handle contributions and benefits under those Acts. Under the same Act, a number of other representatives of medical practitioners and of insured persons were elected by STV. A more formal relation with the NUR began in 1930 and, like that with the Mineworkers, continues to this day. Organisations which very early adopted the single transferable vote for elections not only to single posts (for which it becomes the Alternative Vote or AV) but to committees (and thus to STV in multi-member constituencies and hence PR) include the National Union of Teachers (1922) and the Royal Arsenal Co-operative Society. Some bodies have turned to the Society for advice on how to conduct their elections; others have simply sought a returning officer whose impartiality would not be questioned. The number of such clients grew slowly until 1960, when an election within the Electrical Trades Union was overturned in the High Court because of ballot-rigging. The new leaders of the ETU immediately put all of its large and numerous elections in the hands of the Society, and the publicity given to the judgment and its consequences led to a rapid increase in the number of organisations seeking the Society’s services, many of them using the single transferable vote. In 1982 Frank Chapple, the Chairman of the EETPU (the new name of the union following enlargement), was elected a VicePresident of the Society. (Frank Chapple was Chairman of the Trades Union Congress in 1983).

Besides greatly strengthening the Society’s finances, the direct involvement of the Society in assisting organisations with their elections has led to several million people in the UK now being accustomed to voting by preferences. The development of this side of the Society’s work, which is now known as Ballot Services, eventually resulted in its incorporation in 1969 as a company limited by guarantee. Until 1958, the Society had had no constitution.

The Resolute Advocates

John Humphreys threw himself into the work of the Society with great energy and ability and in 1912 abandoned an assured career in the Post Office to become its full-time secretary, a position he retained until his death in February 1946. Already, in 1911, he had published what long remained the standard work on Proportional Representation. In 1923 Practical Aspects of Electoral Reform followed. Under his direction there was a steady stream of pamphlets and leaflets and he carried on a voluminous correspondence at home and abroad.

John Humphreys’ Post Office experience was valuable in dealing with the sorting of ballot papers, pigeon holes such as he used having become standard equipment. From the start, attention was paid to the practical details of STV elections, it being recognised as necessary that those asked to adopt the system must be shown exactly how it works. Detailed rules for the count were incorporated in Lord Courtney’s bill of 1908 and were reprinted by the Society as a pamphlet.

During the 1914-18 war, minds turned increasingly to means of strengthening the democracy which the war had been fought to defend. Books and articles on the subject began again to appear. Already in 1916 there were statements in parliament indicating an intention to consider far-reaching reforms to take effect in the first post-war election. The new ‘existing circumstances’ might well have led the Royal Commission to recommend the immediate adoption of STV.

Although both elderly, Sir John Lubbock (by then Lord Avebury) and Lord Courtney of Penwith threw themselves into the campaign. Even when over 80 and suffering from failing eyesight, Lord Courtney travelled all over the country addressing meetings and, until the day he died, was working hard in the Lords and through the Parliamentary PR Committee to get STV into the 1917 Representation of the People Bill. His widow, Kate, a sister of Beatrice Webb, continued the work after his death.

While the Society’s usual activities were naturally curtailed by the war, it was far from idle. It maintained a staff of five (four also engaged in war service) and towards the end of hostilities moved into new offices in 82 Victoria Street. The war did not prevent an important tour by John Humphreys to Australia, New Zealand and America. The main reason for this trip was a threat to STV in Tasmania, where a change to a party list system had been proposed. Mr Humphreys’ evidence to a select committee certainly influenced it to recommend preserving the STV system, and led to the filling of casual vacancies by re-counting the deceased member’s papers. He addressed a large number of meetings in Tasmania and other parts of Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada, over a period of about eight months, being well reported and making a good impression. Though no startling practical developments followed, the publicity for STV must have helped pave the way for its applications later in the USA and Canada. The friendships formed were also of great value.

During Mr Humphreys’ absence, the London office was in the care of Alfred Gray, who gave invaluable service until his untimely death in 1944. He married another member of staff, Frances Hodgson, who remained in charge of the clerical side until her retirement in 1959.

On his return, John Humphreys devoted himself to reactivating the PR committee in both houses of parliament; he attended their meetings and the Society became very active at the parliamentary level. The number of meetings increased. The Society sent a memorandum to the prime minister, Mr Asquith, and submitted evidence to the Speaker’s Conference appointed in 1916. Although the 32 members of that conference included only two already committed to PR (Earl Grey and Aneurin Williams), it unanimously recommended the application of STV to London, to boroughs with three or more members, to contiguous boroughs returning together three to five members, and to two three-member university constituencies. Its report was generally welcomed but was opposed by some political organisations, whose pressure caused the government to say that the PR recommendation was not an essential part of the Representation of the People Bill introduced in 1917.

Support in all Parties

Consequently, those clauses relating to PR were left to free votes and they were very narrowly defeated. The figures for the first division show how far opinion in parliament was from hardening on party lines.

|

For Pr |

Against |

| Liberals |

76 |

53 |

| Unionists |

38 |

84 |

| Labour |

13 |

10 |

| Irish Nationalists |

14 |

– |

| Independents |

– |

1 |

| Total |

141 |

148 |

The Lords favoured PR, and had they persisted, with consequent invocation of the Parliament Act, none of the reforms in the bill could have been introduced until 1920. They gave way, the Commons in return conceding STV for the universities, i.e. Oxford, Cambridge and Combined English Universities returning two members each and the Scottish Universities three. These numbers of seats were too small to ensure fair representation of the parties; what the change did do was to give great weight to personality and convert those constituencies into the last strongholds of Independents. Many of the MPs thus elected lent their weight to the cause of reform; among them A.P. Herbert, in his book The Ayes Have It, gave a lucid and entertaining account of how electors behave when given a free and effective vote.

Only weeks before the outbreak of war, the Society’s committee had been discussing the possibility of holding a dinner in Brussels in 1915; with the end of the war foreign contacts were eagerly resumed. By 1919, nearly all the European continental reformers had succeeded in giving their countries proportional representation of parties. At home, defeat on reform of our own parliament found some compensation in other directions.

One of these was the Church of England, where an Act of 1919 set up the Church Assembly, whose members were elected by STY under regulations drawn up by the Society. This resulted from the report of a high-powered committee appointed by the archbishops, chaired by the Earl of Selbourne, a vice president of the PRS, and including at least three other members of the Society.

The same system continues in the present-day General Synod and has spread to some other organs of the Church of England and to some other religious bodies. In 1926 a proposal in the Assembly to revert to X-voting was withdrawn in the face of overwhelming opposition, and in 1953 another attempt was heavily defeated, with the aid of a special leaflet produced by the Society.

It is significant that the Synod has in its deliberations twice passed unequivocal resolutions recommending the government of the day to reform the voting procedure for Parliament and introduce STV. The first resolution, proposed by the Rev. Peter Dawes, was in February 1976 and most recently the call has been renewed by a resolution again put by Peter Dawes, now Archdeacon, and supported by two other prominent members of the Society. The resolution stated that ‘this Synod believes the time has come for a change in the present parliamentary voting system and urges all political parties to adopt a preferential system of proportional representation as a policy commitment for future public elections’.

The reaffirmation of this resolution on 8 November, 1983 was overwhelmingly approved with 80.4% voting in favour. In Scotland also the kirk has identified the defective voting system used in parliamentary elections as indefensible. Supported by the efforts of Donald Macdonald (a member of the council of the Society from 1968 up to the present and honorary treasurer of the Society since 1981) and of James Gilmour (a member of the council of the Society in 1974-83) the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland received a report dated May 1981 from its Church and Nation committee which said, among other things, ‘Since 1972 the committee has urged the adoption of STV/PR for the election of members to any Scots parliament that might be established and the General Assembly have always agreed. This was also the one unanimous recommendation of the Kilbrandon Commission on the Constitution. Now the Committee asks the General Assembly to urge HM Government to appoint a commission to consider the use of a system of proportional representation for the UK parliament so that the will of the electors may be more accurately reflected in the seats gained by the various political parties’. There is no doubt that a large body of church opinion in Britain has seen the distortion of representation resulting from first past the post voting as a matter of equity, a moral issue, to which implementation of STV offers the best practical means of alleviation.

The Mother of Parliaments

Mock election by STV in 1921 – Sorting the ballots

Mock election by STV in 1921 – Sorting the ballots

Mock election by STV in 1921 – Announcing the first preferences

Mock election by STV in 1921 – Announcing the first preferences

British governments have repeatedly shown more concern for fair representation in dependent territories than at home. In 1909, the Society’s help was sought in connection with South Africa, where General Smuts was an enthusiastic supporter of PR. John Humphreys visited that country to supervise STV elections to the municipal councils of Pretoria and Johannesburg and to the Senate. Unfortunately for the subsequent history of South Africa, the original proposal to use STV for both houses of Parliament was watered down, leaving STV only for the Senate which was elected indirectly by the lower house, for which X-voting was used. Consequently, both bodies were very unrepresentative.

Another early instance of Westminster’s tender concern for others was Malta. Thanks to Colonial Under-Secretary L.S. Amery, who had been a member of the Society since 1907 and served on its Council, STV was established there in 1921 and it has been reaffirmed in subsequent constitutional changes. The latest (1981) election has caused trouble, because, of the two parties each nearly equal to the other in votes, the smaller won 34 of the 65 seats. Such variation is within the theoretical margin of error inherent in a body elected entirely from 5-member constituencies but is alleged by the losing party to be due to a gerrymander, and certainly some of the recently re-drawn constituency boundaries look very odd. The Society is trying to reduce ill-feeling by suggesting that, instead of 13 5-member constituencies, as nearly equal in electorate as possible, Malta should have constituencies based on natural communities, with numbers of members proportional to their electorates. An anomalous result might still arise, but with permanent boundaries it could not be attributed to gerrymandering.

The Society’s membership organised in local branches has sometimes been able to take the initiative in important matters. As long ago as 1898 Leonard Courtney had introduced a Bill for the election by STV of the Scottish School Boards but it was not adopted and in 1913 there was still dissatisfaction with elections to those Boards, for which the cumulative vote was used. This did indeed give representation to both of the religious communities involved, but could not be relied upon to do so fairly; if either was able to organise its voters efficiently it was likely to have an advantage over a less organised group of equal or greater size. The Scottish PRS members urged the superiority of STV and one of them in Glasgow, George Quigley, published an effective pamphlet on the subject. Their efforts bore fruit in the Scottish Education Authorities, the first election, in 1919, being the largest application of STV up to that time, it was completely successful and STV continued to be used until the authorities ceased to be separately elected in 1928.

It is interesting to note that one of two major applications of STV in the United States today is for the direct popular election of Community School Boards in New York City. As with the STV elections to the New York City council (referred to later) the moving spirit behind the promotion of STV in the United States is Dr George Hallett who, aged nearly 90, remains actively committed to the cause during the Society’s centenary year. As long ago as 1926, Dr Hallett collaborated with C.G. Hoag of Haverford, Pennsylvania in a comprehensive treatment of the subject entitled Proportional Representation published by Macmillan. He has campaigned vigorously for over half a century for proportional representation which to him, as almost uniformly throughout the USA, means STV. He was elected a Vice-President of the Society in 1974.

Developments in Canada were less satisfactory. Although STV had been used successfully in a number of provincial and municipal elections, it is sad to relate that two enquiries set up by the Federal and the Quebec governments entirely ignored these precedents when considering reform of parliamentary elections. Their examination of European continental party list systems led to no satisfactory conclusion.

However, a Canadian Electoral Reform Society has been formed, largely by the efforts of Paddy Smith of Acadia University, with the invaluable help of Conrad Wright. This society is working hard to improve Canadians’ knowledge of the subject.

Vital work was done by the daughter society in Ireland. The Home Rule Bill being prepared in 1913 originally contained no provision for PR. Limited applications were introduced, and the Proportional Representation Society of Ireland pressed successfully for these to be extended to all elections of the projected parliament. Legislation was suspended owing to the 1914-18 war, and in the interval an event occurred which greatly helped to bring about the acceptance of STV in the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, The town of Sligo, under a succession of highly unrepresentative councils, had been ill-governed to the extent that it became bankrupt and was taken into commission. Its council was restored on condition that it should be more representative, and the Irish PR Society had recently carried out a nation-wide mock election which made the public aware of the means of achieving this. A new council was therefore elected in 1919 by STV, with such conspicuous success that other local authorities throughout Ireland demanded, and got, the same reform. All this paved the way for the inclusion in the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, of STV for the election of the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland parliaments. This was welcomed in Ireland except by the Ulster Unionists, who took an early opportunity to revert to X-voting; the Society’s part in subsequent developments will be referred to later.

Although the Royal Commission had recommended STV for local government elections in Britain, efforts to secure its adoption outside Ireland were frustrated. Among the parliamentary moves by members of the Society was the Municipal Representation Bill, introduced unsuccessfully in the Commons in 1913 but passed by the Lords in 1914; a promised enquiry by a Select Committee might well have led to this being accepted by the Commons, but war intervened.

The great political see-saw, as worked by majority representation

The great political see-saw, as worked by majority representation

Getting a little tired of see-saw politics?

Getting a little tired of see-saw politics?

Emergence of Party Opposition

The Society’s assistant secretary, Alfred Gray, who had served the Society since 1910, was succeeded by Alderman John Fitzgerald, JP, who became secretary on John Humphreys’ death and remained until his retirement in 1959. His particular value to the cause lay in his local government experience and his intimate association with the Labour party, trade unions and the co-operative movement. This was particularly important at a time when electoral reform had come to be looked upon as a Liberal policy, with the two larger parties opposing. As the 1917 division illustrates, that was by no means the case before the 1920’s, but from then on both parties became officially opposed to any change. John Fitzgerald would have nothing to do with the spirit shown in his party’s 1926 conference, when it voted to preserve the existing system because Labour ‘could now make it work for themselves’ instead of for their opponents.

John FitzGerald (right) Returning Officer at the election for the for NUM president in 1945

John FitzGerald (right) Returning Officer at the election for the for NUM president in 1945

Omission of the two main parties to include in their publications any reliable information on electoral systems made the Society’s educational work even more necessary. Under John Humphreys’ leadership it carried out, both centrally from the offices in 82 Victoria Street, acquired in 1918, and through a number of branches, a great programme of public meetings, large and small, summer schools, and so on, including a course of five lectures by Humphreys at the London School of Economics. The bill for PR in local elections which had passed the House of Lords was repeatedly re-introduced but without success in the Commons. In 1923 the second reading was lost by only 12 votes. Private members’ bills for STV in parliamentary elections were also introduced, and the merits of STV were stressed in discussions on reform of the House of Lords.

The Society gave evidence to the Royal Commission on London Government, appointed in 1921, and published its evidence as a pamphlet. The LCC itself favoured PR similar action was taken in regard to the Royal Commission on Local Government (1927) and the one which led to the creation of the Greater London Council by the Act of 1963.

Moving from the parish pump to the far-flung Empire, the Society gave evidence to the Simon Commission on India – also, at about the same time, to the Speaker’s Conference of 1930. The Society’s report for that year draws attention to the contrast: objectivity in the former, division on strict party lines in the latter. ‘In respect of India, British parties took a detached and non-partisan view; in respect of the reform of the House of Commons opposite conditions prevailed.’ However, at least one member of the Conference admitted to having changed his mind as a result of the Society’s evidence, and a majority of the Conference agreed that if there were to be any change it should be to STV. The Electoral Reform Bill submitted by the (minority) Labour government did not accept this, proposing instead the alternative vote. The Liberals protested but agreed to support this as a second best; in the event the government fell and the bill never became law.

The general election of 1931, with its exceptionally distorted result, gave new ammunition to advocates of reform, but at the same time made it more difficult, the government with its hugely inflated majority being most disinclined to listen. And even Labour, reduced to a quarter of its proportional share of the seats, did not absorb the lesson. 1935 was not a great deal better. With no hope of changing the government’s mind, the Society redoubled its efforts to educate public opinion. Campaigns in by-elections began, and were carried on under Mrs W.J. Baird with her decorated car. John Humphreys broadcast on the new BBC, and a manifesto was drawn up, signed by men and women eminent in public life. The Society’s reports and other pamphlets continued to analyse elections at home and abroad, under systems good and bad. The report for 1937-8 was one of the earliest to draw attention to the evil effects of Northern Ireland’s reversion to X-voting – the Society was beginning a campaign to turn again to STV which saw final success in 1973.

The same report contains an account by John Humphreys of his visit to New York to observe the STV election to its city council. Unfortunately, in 1947 a campaign for reversion to X-voting succeeded. It was backed by the wealth of Tammany Hall (which spent $35,000 against $4,000 by the Keep Proportional Representation Committee) and aided by a ‘red scare’, Communists having won two seats in the 1945 election – their exact proportional share, which they would in any case probably have lost in the changed climate of 1947. The experience encountered by advocates of STV in the USA, (reinforced by the Society’s experience in Ireland, referred to elsewhere in this short history) demonstrates the vital continuing role of the Society to consolidate and defend progress whenever success is achieved.

Among other distinguished supporters at that time was Sir Robert McDougall. His name still figures prominently in the Society’s record because he left a generous legacy in memory of his father, Arthur McDougall, which was used to set up a charitable trust in 1948 to finance research in political and economic science, functions of government and methods of election.

World War II

The second world war brought an unavoidable break in the work. Not, however, by any means complete, since the time was used in planning for the future – alone and in conjunction with other bodies striving for a better world. Both national and international organisations were involved. In conjunction with the Universities Bureau of the British Empire and with the Workers’ Educational Association, the Society organised more essay competitions on possible improvements in the post-war House of Commons. The British government itself set up a committee to examine the difficulties of redistribution and various other matters involved in an election soon after the war, and offered, if parliament desired, a Speaker’s Conference on possible changes in the electoral system. The then chairman of the Society’s Executive, G.W. Rickards, MP, tabled a motion asking for such a conference, which was welcomed by the prime minister (Churchill) and accepted after a debate.

The home secretary (Herbert Morrison) seemed to have modified his earlier opposition to PR and paid a notable tribute to the Society which, he said, had ‘helped people to understand it very much better than in earlier days’. The Conference was appointed and consisted of 29 MPs from all parties in proportion to their strengths in the Commons (as distorted by the 1935 election), and one peer from each of the three main parties. The Society submitted a memorandum but all proposals for changing the system of election were rejected. Sir Leslie Boyce, Conservative MP for Gloucester, described the report of this conference as ‘opportunist party politics at their worst’.

Consequently, while the other European countries resumed elections under systems giving fair representation of their parties, Britain alone persisted with one which, having previously given greatly exaggerated power to the Conservatives, now exaggerated the swing against them. It also gave a false impression of ingratitude to Churchill. It was in these circumstances that the Society resumed normal work after the war. The doyenne of electoral reformers today, Enid Lakeman, joined the staff as Research Secretary on her release from the Air Force. She speaks glowingly of the great pleasure of serving under John Humphreys for the last three months of his life. That short period, she says, left an impression out of all proportion to its length.

Very early in his career as Secretary, John Fitzgerald was called upon by the Allied Military Government to help in preparation for resumed elections in the British zone of Germany. Unfortunately, he was called in too late to persuade the Germans to adopt STV; they were dissatisfied with the wholly impersonal party list system of the Weimar Republic and imagined the British system to be very personal. Under the guidance of British members of the Military Government, including Mr Austin Albu, a member of the Labour Government of Mr Attlee, they substituted the system which in essentials still operates: half of the Bundestag is elected like the House of Commons and the other half of the seats are allotted to the parties so as to make their total representation proportional. In 1951, Mr Fitzgerald was again employed by HM Government, this time to supervise the first STV election of the Gibraltar Legislative Council.

A memorial fund was raised for John Humphreys and it was decided to devote it to publication of a book to replace his own work. A new edition, bringing the 1911 book up to date, had been recognised as needed but was never achieved. The writing of the new book was entrusted to Enid Lakeman, in collaboration with James D. Lambert, a civil servant in the Foreign Office, later editions being revised by Miss Lakeman alone, with a change of title from Voting in Democracies to How Democracies Vote. This won recognition as a standard work and was succeeded in 1982 by Power to Elect, other members of the Society have published important books, notable among them being Dr J.F.S. Ross, whose Parliamentary Representation (1943 and 1948) was a pioneer in the study of MP’s occupations. In 1982 a work was published by Robert A. Newland who was Chairman of the Society from 1968 to 1977. His Comparative Electoral Systems is of particular note as a detached treatment of the logical and practical effects of different systems, written without resort to anecdote.

The early post-war period was one of increasing financial difficulty. Another new member of staff, Albert Sumption, gave valuable service, especially in running campaigns in parliamentary by-elections, but the Society was able to employ him for only three years, until June 1950, at which date Enid Lakeman was diverted to work on the book financed by the Humphreys Memorial Fund, and later to a study of Malaya published by the Arthur McDougall Fund. A moderately successful effort was made to get the office work done by volunteers from among the members, ending when Miss Lakeman returned to the full-time staff in May 1952. She succeeded John Fitzgerald as Director on his retirement in September 1960.

Why We Changed Our Name

This period saw a prolonged discussion about the Society’s name. It was increasingly felt that “Proportional Representation Society” was too liable to suggest a connection with the continental party list systems. A score of other names were suggested, a postal ballot of all members produced a majority for Electoral Reform Society, and this change took effect at the end of I959.

The financial difficulties affected publications. Representation had ceased as a separate journal in 1923, but the annual reports up to 1950 contained a review of important elections and other events throughout the world. There was then a gap and a final publication in that series covering I 950-53. A magazine, Humphreys, was started by Michael Birkin in honour of the Society’s distinguished secretary and ran from 1947 until 1953, The lack of a regular publication was keenly felt and the need was for a time partly met by a quarterly, at first duplicated and then printed, which ceased in 1955 for financial reasons. Publication was resumed at the end of 1960, reviving the old title of Representation. Until the end of 1971 this was only a duplicated sheet, usually of four pages, very largely written by Enid Lakeman; it then changed to substantially its present form, becoming a journal of some repute with a wide range of contributors. Members now receive also a quarterly Bulletin devoted to the Society’s internal concerns.

Involvement with an official enquiry occurred again in 1961, when Harold Glanville and Enid Lakeman gave evidence before the Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London. That Commission led to drastic changes in many other aspects of London’s government but refused to recommend any change in the system of election. It was argued that London could not have a different system from the rest of the country – regardless of the fact that X-voting in wards electing up to nine members had made London’s election results almost uniquely bad, with highly unrepresentative councils and rigid party domination extending to administrative details. The Society gave evidence also to the Maud committee on local government (1967), but while this led to an upheaval in Britain’s local government structure, it left the voting system unchanged. The Maud committee produced a very valuable report, including information from other countries, but failed to draw conclusions regarding voting systems.

Also, in 1967 there appeared the report of another Speaker’s Conference, to which the Society had given both written and oral evidence. This report is of far less value, for it simply recommends no change, without publishing any of the evidence or giving reasons for its conclusions. A Speaker’s Conference is in any case unsatisfactory, since it consists of MPs, all with preconceived ideas on the matter and subject to party pressures. Since the war the division had been on rigid party lines. For those reasons, a campaign had already been launched for a new Royal Commission, whose members would of course be chosen for their ability to consider evidence impartially, who would meet in public and would publish a comprehensive report. The campaign had about a hundred sponsors, including MPs and peers of all parties and men and women distinguished in other walks of life. A high-powered deputation was received by the Home Secretary in 1955, but no action followed. The prime minister of that time (Sir Anthony Eden) in a letter to the committee wanted proof of a much larger volume of support.

Unofficial enquiries in which the Society has taken part have included one by the British Council of Churches in 1981. After prolonged discussions in depth, representatives of the various churches, together with Michael Steed and Enid Lakeman on behalf of the Society, agreed that the method by which the General Synod is elected ought to be extended to the House of Commons.

A Royal Commission, known as the Kilbrandon Commission after its chairman, was actually appointed, in 1973, not specifically on electoral systems but on the constitutional question of devolution, involving separate parliaments for Scotland and Wales. Lord Kilbrandon became a Vice-President of the Society in 1980. The Commission was unanimous on just one point: that if any such assemblies were set up they must be elected by the single transferable vote.

This recommendation, however, was not included in the resulting bills for Scotland and Wales – a curious omission by a government that had so recently restored usage of STV for the people of Northern Ireland. The bills for both Scotland and Wales were put to the people in referendums, with the unprecedented provision that no change would be made unless accepted by 40% of the entire electorate. Both failed to meet that condition.

Triumphs In Ireland

In contrast to these frustrations, the Society was able to record two major triumphs, in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland. The first hint that action might be needed occurred in 1955, when Sean Lemass voiced the opinion that Ireland would be better off with the British voting system. (Not, of course, referred to as such but by the euphemism of ‘straight vote’.) In a press conference in August 1958, Eamonn de Valera announced that his government would table a bill for that purpose. Opposition proved far stronger than he had bargained for, and the battle raged until the final vote in June 1959. Numerous false statements were made about the alleged advantages of the ‘straight vote’ (such that it produces government by the majority!). For seven months the Society (again mainly in the person of Enid Lakeman), continuously told Irish audiences what really happens under X-voting. The most effective argument was that it means having to vote for the one candidate selected by one’s party; the Irish clearly set great store by their power to choose the individual they want. The campaign was hampered by the absence in Ireland of any non-party organisation equivalent to the Electoral Reform Society; the one which had existed disbanded when its aim was achieved. The Society had to depend initially on Sein MacBride and his Clann na Poblachta party; various other bodies later gave Miss Lakeman a platform, and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions intervened almost too late but very effectively. The referendum result was so close (486,989 to 453,322 for retention of PR) that everyone concerned was entitled to say, ‘But for me!’. That close vote prompted de Valera’s Fianna Fail party to try again nine years later, when it was easily defeated by a margin of 3 to 2. The difference was almost certainly due to the advent of television, which gave debates and solid background information to electors, too many of whom had previously been dependent on the Irish Press which in those campaigns printed nothing on the pro-PR side.

The second referendum coincided with the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland, and the Society’s window display in the Republic included photographs which clearly implied the dangers of polarisation with the caption “They’ve got the ‘straight vote’”. The Society had long been drawing attention to the evil effects of Northern Ireland’s abandonment of PR, and in 1966 a speaking tour by Enid Lakeman covering both parts of Ireland led to an article in Representation stressing the great contrast between the two, especially in relations between Protestants and Catholics. Sustained agitation by the Society, including publication in 1970 of a report by James Knight, must have contributed to the final decision by the Conservative government, backed by the opposition, that, whatever might be the case for X-voting in Britain, it was having disastrous effects in bitterly divided Northern Ireland. The 1969 election frustrated the efforts of Terence O’Neill, Northern Ireland’s prime minister (later Lord O’Neill of the Maine), to persuade the majority into a more conciliatory attitude, and Representation of April 1969 contained an article showing how STV would have enabled the voters to support his policies instead of appearing to reject them. The British government found it necessary to dissolve the Stormont parliament and substitute direct rule, and in June 1972 it was announced that a new Assembly, and local councils, would be elected by STV. The Society was engaged to train the returning officers and also contributed to explaining the new system to the voters. In co-operation with the Chief Returning Officer for the Province, the then Society chairman, Robert Newland, in conjunction with Major Frank Britton, the Controller of Ballot Services, arranged a series of familiarisation courses for Deputy Returning Officers and their staffs. Robert Newland, Frank Britton, James Knight, Gervase Tinley and other Society members travelled to Belfast to assist in this work. The first elections following restoration of STV were held in 1973 and went very smoothly. Several members of the Society observed the arrangements in detail and were able to confirm at first hand how readily the electorate had accepted and used STV despite the tense political atmosphere. James Knight has published valuable analyses of these and subsequent elections.

The Society found it necessary to discourage exaggerated expectations. The idea that a large ‘moderate’ majority would emerge was never realistic; nevertheless, such tendency as did exist to cross the sectarian lines was encouraged. Notably in local government, councillors, who had previously been at daggers drawn found themselves able to work together on projects for the benefit of the whole district.

During all this period of activity in Ireland, the Society’s own situation was changing. Successive expiries of leases forced removals, first to Eccleston Square in 1953, to the Albany Institute in Deptford at the end of 1959, then in 1966 to divided premises, the main office being in Whitehall Court while the business of conducting elections for other bodies was carried on in Nicholson Street, Blackfriars. Both sections were reunited in nearby Chancel Street in 1969.

Ballot Services Expand

A great expansion of the Ballot Services side of our activities began in 1960, bringing valuable publicity, introducing many additional thousands to STV and improving the financial position. The crucial event was the high court action against officers of the Electrical Trades Union for ballot rigging. Before the matter reached the court, the Society had offered both sides its services as a returning officer of recognised integrity, and this offer was taken up eagerly by the new officers urged on by memorable encouragement from Mr Justice Gardiner who said in his judgment that if he were a caliph under a palm tree he would put the Electoral Reform Society in charge of the next ETU election. The wide publicity set off a train of enquiries from other trade unions and similar bodies, one satisfied customer passing on a recommendation to others.

With the possible exception of the ETU (as it was in 1960) no trade union work has brought the Society into greater prominence than its long-established place in the counsels of the National Union of Mineworkers. Elections for President and General Secretary in recent times have involved such nationally known figures as Lawrence Daly, Joe Gormley (now Lord Gormley), Arthur Scargill and Peter Heathfield. Under the leadership of Joe Gormley the NUM was guided through a period of disturbed industrial relationships including the national strike associated with the fall of the Conservative government in 1974. This period saw a number of referendum-type ballots of the NUM membership administered with the assistance of the Society on behalf of the National Executive of the union. This has been the traditional method of communicating within the industry, that is, via the NUM rather than directly by the Coal Board.

With the various mineworkers’ ballots the Society was brought very much into the public eye. It did not seek the limelight in carrying out this work which it has always approached as a process which, by honest assessment of opinions honestly held, could help create rapprochement and lessen the risk of damaging confrontation. Television and press coverage of the NUM ballot results brought publicity to the Society and through the skill of Frank Britton an image of professionalism and integrity was projected which served the Ballot Services department well in building its portfolio in succeeding years.

During the last two decades, the intense public interest in the coal industry has often led politicians and journalists to approach the Society for inside information on ballots. At times there have been thinly disguised attempts to discredit the whole process but the Society has managed to avoid leaks and has steadfastly maintained the confidentiality of its clients.

In the NUM, balloting takes place ‘at the pithead’ and the ballot papers are forwarded to the Society’s office, where they are counted in the presence of NUM officials. In other cases, Ballot Services exercises a much wider measure of control. In the EETPU, as one of the safeguards introduced following the previous malpractices, it carries out all operations, from the printing of ballot papers and their dispatch to members’ private homes. It now uses special paper-handling machinery and has recently introduced a computer.

While in the coal industry all our ballots have been carried out for the union, in British Steel the management wished to seek the views of its workforce directly and, under the chairmanship of Sir Charles Villiers, when it initiated a period of widespread re-organisation, it asked the Society to carry out a mammoth survey of its employees. British Steel’s first thoughts were to make the terms of the current negotiations the subject of a ballot which would effectively have gone over the heads of the union leaders. The unions were bitterly opposed to this. Frank Britton, with the Society’s Chairman, Gervase Tinley, advised against risking a dangerous confrontation and the management agreed to limit the survey to a referendum on whether the employees wished for a ballot on the management’s proposals.

There was also a conciliatory suggestion to the effect that management would prefer the ballot to take place under the aegis of the union. This event became known as ‘the ballot about a ballot’ and it greatly helped resolve a major industrial dispute. It can be claimed to have had a profound effect on the steel industry and the climate of industrial relations.

From 1975 onwards, Mr (now Sir) Michael Edwardes involved Ballot Services in top-level discussions on the complete reorganisation of British Leyland. Frank Britton was ably assisted in these discussions and in carrying out opinion surveys by postal ballot of all British Leyland employees by Peter Crisell, who now manages the ballot services department. The surveys were an unqualified success, attracted intense public interest and added to the Society’s record of efficiently handling very large ballots in demanding circumstances. They demonstrated the Society’s policy of using ballots to locate areas of possible agreement, reducing the tendency of some managements to fight their own staff and lending support to employees willing to seek grounds for co-operation.

Some organisations are governed by Royal Charter and consequently must obtain Privy Council consent to any constitutional change. These include the Royal Institute of British Architects, which is one of the many professional bodies using STV for their internal elections. It has also retained the Society as advisors.

The General Medical Council is one of a small group of organisations governed directly by act of parliament, and so needing an amending bill to change its basic regulations. A committee under the chairmanship of Sir Alec Merrison, F.R.S., was charged with examining the method of election of the Council and turned for advice to the Society, whose recommendation of STV was accepted. It became law, ironically, by the vote of MPs for whom STV in any public election was regarded as unthinkable. Robert Newland and Frank Britton worked out the detailed procedures and the first election took place in 1979, the Society being commissioned to receive and count the voting papers and submit a detailed report. The medical profession saw that the results were just and saw STV operating as a unifying force. The often-conflicting sectional interests each got fair representation – including hospital doctors, GPs, junior and senior doctors, immigrants and women,

Following these developments in the medical profession, the General Nursing Council of England and Wales and eight other statutory authorities were absorbed into a new structure entitled the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (UKCC for short!) This needed to establish satisfactory electoral procedures, sought the advice of the Society and accepted its recommendation for STV. The first election was carried out in 1983 under Seamus Burke’s supervision. There are, of course, far more nurses, midwives and health visitors than doctors and their use of STV represents another major advance.

Industrial and commercial ballots can have political consequences. In 1975 Ballot Services was asked by a group of shipping companies to assist in establishing a committee that would accurately represent the participating organisations. The approach came through a leading member of the Baltic Exchange and led to Frank Britton being called into consultation with the association at its AGM in Hamilton, Bermuda. While there, he was asked by the Minister of Marine and others to advise on the constitutional problem created by increasing tension between the black and white sections of Bermuda’s population exacerbated by the adversary politics typical of assemblies elected by X-voting. Their response was immediate: STV was ‘just what Bermuda needed’! Its unifying and healing effects could, they felt, be of great benefit. They could not forecast the reaction of the political parties, but invited Frank Britton to return for a full round of multi-party discussions including meetings with the prime minister and the governor-general.

Dr Garret FitzGerald TD

Dr Garret FitzGerald TD

The Irish general election of June 1981 gave an excellent opportunity for representatives of the Bermudan government to observe STV in actual operation. Sir John Plowman, previously minister of marine and by now deputy prime minister of Bermuda, and Senator Michael King were accompanied by Frank Britton, Gervase Tinley and Seamus Burke, providing expert comment on the conduct of the election in Dublin. The Irish authorities were generous in their co-operation, and a meeting with Dr Garret FitzGerald enhanced the visit. The previous year he had accepted the Society’s invitation to become its president, in succession to Sir Lance Mallalieu who died after barely 18 months in office. Dr FitzGerald was then leader of Fine Gael and after the 1981 election was elected Taoiseach by the Dail and formed his first administration. Thus, the Bermudan visitors were able to meet the Society’s president, who was able to give expert practical observations not only as a party leader but also as a man actually in process of winning the election which took him to the office of prime minister.

Unfortunately, the Bermudan political parties were evenly balanced in the legislature, while the distribution of votes was such that with X-voting a bare majority of votes might give either party a landslide in seats. In both parties, there were enough people influenced by this temptation to frustrate reform at that time. However, for a while the United Bermuda Party included the adoption of STV in its programme and the time will surely come for another, and successful, attempt.

It would be wrong to conclude the description of the work of Ballot Services without reference to an area of increasing significance. Member participation in the running of pension schemes has led to the inclusion of member representatives on pension fund committees and boards of trustees. The Society has given advice to a number of major pension funds and helped to devise schemes of election, as well as acting as returning officer. The Shell Pension Fund is one which has publicly acknowledged the effectiveness of this work and of STV.

From the account given it will be seen that the work of the Society’s Ballot Services covers not only elections but ballots on strike action, amalgamations, changes of name, and on one occasion a referendum among the people of Orkney and Shetland to establish their views on devolved government for Scotland. This varied work necessitated the formation of a company to handle its business affairs and led to the incorporation of the Society (1969) as a company limited by guarantee, and expansion of both premises and staff. Major Frank Britton had joined the staff in 1963, becoming Controller of Ballot Services. He was also the Society’s Executive Secretary until his retirement in 1979.

Fresh Resentment Aroused

Public interest in electoral reform showed signs of reawakening already in 1970 and an addition to staff helped the Society to take advantage of this. Eric Syddique had for some time been giving voluntary help and in 1972 was engaged permanently as an assistant to Miss Lakeman. In addition to acting as Clerk to the trustees of the Arthur McDougall Fund, he is now the Society’s Education Officer.

A surge of protest was produced by the flagrantly distorted result of the February 1974 election. One effect was the formation of other reforming bodies, with which the Society has co-operated as far as their aims coincide, Fundamental differences on the approach to reform first became evident in a committee set up by the Hansard Society in 1975. This examined various electoral systems and its published evidence pointed clearly to the single transferable vote form of PR as the best. Nevertheless, its recommendation (Baroness Seear dissenting) was for the West German system or a variant of it. This recommendation clearly resulted from thinking in terms of the proportional representation of parties, coupled with the belief of many MPs that being the sole member for a constituency gives them a close personal relationship with their electors. In 1984 the Society commissioned an independent survey by Market & Opinion Research International (MORI) to examine this relationship. Throughout its century of active existence, the Electoral Reform Society has adhered to the belief that it is people, not parties, for whom fair representation must be sought, and that this is possible only when voters are given a wide and free choice among candidates in a constituency that elects several members and can therefore reflect several different opinions. It is stating the obvious, but necessary to do so, that just and fair representation of people will ensure, as a by-product, just and fair representation of parties. The reverse is by no means necessarily true.

In 1976 the Society took part in the formation of the National Committee for Electoral Reform, which was set up as an umbrella organisation to co-ordinate, and especially to raise funds for, the efforts of all bodies seeking to replace Britain’s existing system by a better one. It has from the start embraced the reform groups existing in all the main parties, besides a number of non-politicians prominent in other walks of life. From it arose the Campaign for Fair Votes, which at the time of the Society’s centenary was working to secure a million signatures to a petition for a referendum on a PR bill. A referendum because it was felt that the electors, so many of whose votes are now ineffective, are better qualified to decide this question than are MPs with a vested interest in the system by which they acquired their seats.

Recent Developments at Home and Abroad

In the field of local government a success was registered in 1981, in the Isle of Wight. Medina borough council had passed a resolution that it should ‘adopt a method of electing committees, sub-committees and other bodies which is as democratic as possible, ideally using the single transferable vote’. It asked the Society for help and Mari James (who as well as serving on the council of the Society since 1976 has been Chairman of the Liberal Action Group for Electoral Reform (LAGER) and is a member of the council of the National Committee for Electoral Reform) addressed a meeting of the full council and conducted a mock election. The ‘mock’ committee thus elected proved to be a perfect reflection of the councillors’ opinions, they were convinced that the change was desirable, and it took effect from 14 May 1981.

Turning from local to international government, the Society involved itself deeply with the elections of the European Community. The Community’s parliament consisted originally of persons nominated from the parliaments of the member states, but the Treaty of Rome envisaged their eventual direct election, by a system common to all members. Seeing that the body to be elected was concerned with European rather than national questions, there was a particularly strong case for using the single transferable vote, so as to enable voters to express their opinions on such questions without having to desert their national party. However, there were great obstacles in the form of the continentals’ unfamiliarity with STV and the British government’s antipathy to any form of PR. This was overcome to the extent that in 1977 the government put forward a bill incorporating ‘regional lists’, voting to be in regional multi-member constituencies, each party submitting a list of candidates and voters to mark one candidate in one list. This, however, was rejected by the House of Commons. The elections having been delayed far beyond the intended date, it was finally agreed to hold them in June 1979, each member state using its own system. The British result was highly distorted and upset the balance of the whole parliament, to the great annoyance of other members. However, one gain resulted from the Society’s work in Northern Ireland. Because the X-vote would certainly have excluded the large Catholic minority from representation, Northern Ireland was allowed to use STV as for its other internal elections. Not only did this give fair representation but the turnout was nearly twice as high as in the rest of the United Kingdom. Agitation and negotiation have continued ever since on the need to devise a satisfactory common voting system for Europe and have included circularisation of all MEPs by the Society, but the 1984 elections will again be held under the member states’ own systems, and one can only speculate at the time of writing that there will be, no doubt, equally unsatisfactory results.

Beyond the bounds of the EEC, an extension of the Society’s international activities has been associated with changes to its internal structure. After the retirement of Enid Lakeman as Director and Frank Britton’s retirement as Executive Secretary, it appointed in 1980 a Chief Executive, Seamus Burke. One of his first enterprises was a visit to New York during their presidential election, and this had important consequences. He met George Hallett and, among his colleagues, Archibald Robertson and Lucian Vecchio. As a direct result the Society became involved in the STV elections of the New York City Community School boards.

Public elections in New York are administered by the New York City Board of Elections. With the exception of the Community School Board elections, voting is done by the use of voting machines which are warehoused, maintained and operated under the supervision of the Board of Elections. To administer the Community School Board elections, where voting and counting is by manual procedures on paper ballots, the Board of Elections invited tenders from organisations including Proportional Count Associates of which Messrs Robertson and Vecchio (who are also members of the Society) are principals. For the May 1983 elections PCA included in their successful tender a provision that the Society would provide observers. Accordingly, Gervase Tinley and Seamus Burke attended the counting process and brought back a wealth of experience as well as re-opening links with advocates of STV in the USA. STV is of great importance for the representation of ethnic and religious minorities. Indeed it is difficult to conceive stable and workable bodies composed of representatives of so many diverse interests as the New York School Boards being capable of election by any other system.

On his visits to New York in 1981 and 1982 Seamus Burke visited the United Nations building and discovered that there was scope for some body that could give advice on systems of election to countries desiring it. Curiously he found that there was no operational division within the UN specifically entrusted with an educational and advisory role on electoral systems. Seamus Burke developed the idea of the Society filling this void, and received support from the United Nations delegations of both the United Kingdom and the Irish governments: after he had given evidence in person at a plenary session of a sub-committee of its Economic and Social Council the Society was granted formal consultative status with the UN in May 1983. At the time of writing no direct activity has flowed from the Society’s link with the UN but time will bring circumstances, such as those arising in Grenada, which will no doubt come into play in ways which cannot yet be foreseen.

Back Home Again

At home, the last three years of the Society’s first century have seen a development which intimately concerns its cause. As a consequence of the X-vote which stifles the expression of different opinions within any party, certain members of the Labour party who considered it to be taking the wrong direction were driven to leave it and form the Social Democratic Party, which was joined by a larger number of people who had not previously been active in politics. The Social Democrats’ ideas have much in common with the Liberals’ and an alliance of the two was welcomed enthusiastically by the Liberal Conference of 1981. Co-operation between people of different parties does appear to be widely desired among the electorate, but X-voting puts great difficulties in its way. This became painfully clear when the Alliance, to have any chance in the general election of 1983, was forced into arrangements to ensure than only one of the two parties contested any one scat- an arrangement which would be quite unnecessary under STV.

With a view to evolving policies agreed upon by both parties, the Alliance set up committees, of which the first examined the electoral system. The Society gave evidence to this, and had the satisfaction of seeing that the report (Alliance Commission on Constitutional Reform under the chairmanship of Sir Henry Fisher) recommended what it called ‘community proportional representation’, i.e. the single transferable vote in multi-member constituencies corresponding to natural divisions of the country.

Sir Henry Fisher’s name is given to a wide-ranging investigation also of Lloyd’s of London. The ‘Fisher Report’ of May 1980 came at a time when a number of scandals had been revealed in the operation of various underwriting syndicates, and central to its recommendations for reform were proposals for a more responsive and representative governing body. The ‘Fisher Report’ contains the following words:

“we suggest that consideration should be given to adopting the ‘single transferable vote’ system (as recommended by the Electoral Reform Society), which, though complicated to explain, is simple for voters to operate (they simply place as many candidates as they choose in order of preference) and does accurately reflect voters’ opinions.”

Although many changes have been effected within the organisation of Lloyd’s, the most sensible suggestion quoted above has yet to be adopted.

The result of the 1983 general election put the attainment of STV for parliamentary elections further off in as much as it gave a huge parliamentary majority to a party whose leader has publicly opposed PR, but on the other hand it gave further evidence of the need for change. In particular, the notion that X-voting is acceptable in a two-party situation drops out of the argument, for in 1983 and 1984 there is clearly no prospect of a two-party election.

The X-vote belongs to the past age of illiteracy. The members of an educated electorate, confronted with problems of great complexity, deserve a system that will encourage them to think and enable their thoughts to have effect. The Electoral Reform Society goes into its second century confident that good sense will at last prevail.

The End of the Beginning

The Society entered its hundredth year with the Council Members and Officers shown on page 28. It is indicative of the Society’s standing that it has as its President the Taoiseach (prime minister) of Ireland, Garret FitzGerald, an internationally renowned politician, who, significantly, assumes the Presidency of the Council of the European Communities at the time of the Society’s centenary celebrations.

Prominent in the Society for many years, the Chairman of the Council, Gervase Tinley, has worked tirelessly to advance the Society and to arrange appropriate and beneficial celebrations of its centenary.

The Chairman, Council Members and Officers have all, in their several ways, sought to make the Society a more active influence in the United Kingdom and in the Irish Republic. Through formal and informal education, in the press, on radio and television, with the active help and support of the Society’s members, the case for electoral justice has been made.

The Society enjoys the unique advantage of providing a fee-earning service to a variety of institutions and other organisations for which it conducts elections and other ballots. Many of these elections, of course, demonstrate the benefits of preferential voting and, through the Society’s agency, a growing number of people are exercising real and extended democratic influence through the ‘voter’s choice’ system, the Single Transferable Vote.

Council Members, being British themselves, are conscious that the United Kingdom parliament and British local authorities have not yet adopted STV and they have a burning desire to capture these glittering prizes. In this, they share the aspirations of the Society’s members, the hopes of millions of their fellow citizens, and the good wishes of their friends in Europe and beyond.

The Electoral Reform Society of Great Britain and Ireland

Staff and Council

|

The Council |

| President |

The Hon. Dr Garret FitzGerald |

| Chairman |

Gervase E.N. Tinley |

| Vice Chairman |

Peter S. Kelway |

| Deputy Chairman |

James S. Knight |

| Honorary Treasurer |

Donald P. MacDonald |

| Members |

Bernard Black

Eric Chalker

Marjorie L. Deakin

Stephen P. Freeland

Mari P.A. James

David Mason

Ronald G. Medlow

Robert A. Newland

Eric A. Rowe

Donald Simpson F

Francis Walsh

James Woodward-Nutt |

| Chief Executive |

Seamus Burke |

| Manager Ballot Services |

Peter R. Crisell |

| Administrative & Education Officer |

Eric M. Syddique |

| Deputy Manager -Ballot Services |

Owen Thomas |

| Campaign Manager |

Jacqueline Alo |

Vice-Presidents

Lord Avebury

Lord Banks

Roderic Bowen

Major Frank Britton

Capt.C. Valentine Brook

Professor Peter W. Campbell

Frank Chapple

The Bishop of Chelmsford Tom Ellis

Lord Gladwyn

Dr George Hallett

Ronald Hardy

Lord Kilbrandon

Miss Enid Lakeman

Miss Sheelagh Murnaghan

Oliver Napier

Robert A. Newland

J.B. Priestley

Lord Roberthall

Rt Hon. J. Jeremy Thorpe

Richard Wainwright

Presidents

1884-1913 Sir John Lubbock (later Lord Avebury)

1913-1917 Fourth Earl Grey

1917-1953 Fifth Earl Grey

1967-1968 Lt-Col. Harold Brightley

1970-1978 Rt.Hon. Dingle Foot QC, MP

1978-1979 Sir Lance Mallalieu QC

1980- Dr Garret FitzGerald TD

Chairmen

1884-1918 Lord Courtney

1918-1936 Lord Parmoor

1937-1942 Cecil H. Wilson MP

1942-1943 G. W. Rickards MP

1943-1948 T. Edmund Harvey MP

1948-1950 Rev. Gordon Lang MP

1950-1954 Piers Gilchrist Thompson

1954-1956 J. Jeremy Thorpe PC, MP

1956-1968 Lt-Col. Harold Brightley

1968-1977 Robert Newland

1977-1979 Eric Rowe

1979- Gervase Tinley