Introduction

By Darren Hughes

The past two years have not been good for the House of Lords.

The past two years have not been good for the House of Lords.

Despite legislation to expel those who commit crimes or fail to attend, there are still those who do very little yet continue to collect large pay cheques.

New appointments based on patronage continue, swelling the already supersized chamber. The upper house is being treated by some as a retirement home or private members’ club. This is no fit state for the Mother of all Parliaments.

At the end of 2015 we conducted an audit of the House of Lords, Fact vs Fiction. It challenged claims that the Lords is a beacon of independence and professional diversity and demonstrated the huge democratic and financial cost.

Indeed, in the 2010-2015 parliament, £360,000 was claimed by peers in years they failed to vote once. On independence, over a third of Lords (34%) previously worked in politics. And we found that the Lords represents only a small section of society: 44 percent of Lords listed their main address in London and the South East, while 54 percent were 70 or older. Just 1 percent came from manual backgrounds.

The problems of an unrepresentative, inefficient and growing house have not improved since those revelations. Our research shows that 109 peers failed to speak at all in the 2016/17 session. sixty-three of those claimed expenses – claiming a total of £1,095,701.

More shockingly, 33 peers have claimed nearly half a million pounds between them while failing to speak, table a written question or serve on a committee in the past year. Particularly at a time when Parliament is dealing with major legislative upheaval, this kind of behaviour is unacceptable.

We know the upper house is grossly oversized but we also know that the bulk of the work of the Lords is carried out by a smaller number of peers – something that is finally being recognised by the upper house. The Lord Speaker’s Committee on the size of the House was set up recently to discuss how to shrink the supersized second chamber. In October 2017, they released their plans to reduce the size of the Lords to 600 in 11 years and move to 15 year terms by 2042 – by which time NASA plans to have landed humans on Mars.

Calls for reform are often dismissed on the basis that the Lords is a bastion of independence. We can reveal the truth is far from it. Our analysis shows that nearly 80 percent of Conservative peers didn’t once vote against the government last year. Of the Labour peers who voted, 50 percent voted against the government more than 90 percent of the time. And non-partisan crossbenchers often don’t turn up – over 40 percent voted fewer than 10 times last year: leaving decisions in the hands of the party whips.

It’s time for a much-smaller, fairly-elected upper house in which the public can have faith.

This report lays out the state of Britain’s second chamber today. It’s now up to politicians to meet the challenge, before trust in our democracy falls even further.

Darren Hughes

Chief Executive

Electoral Reform Society

Acknowledgements

The Electoral Reform Society would like to thank Emma Levin, Jess Garland, Chris Terry, Tomasina Wallman, Josiah Mortimer, Douglas Cowan and Charley Jarrett for their contributions to this report.

The high cost of small change

Small change

In 2015 we published Fact vs Fiction, a review of the House of Lords in key statistics. We looked at cost, size and independence, as well as how well the Lords represents the UK in the 21st century.

Since that report, measures to allow peers to resign voluntarily, to be expelled for failure to attend or for conviction for a serious offence have been introduced – through the House of Lords Reform Act 2014 and House of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act 2015.

Following on from these changes, though some peers have resigned or been expelled, we find that on key measures, little has changed.

A supersize house

The House of Lords is the second largest legislative chamber in the world behind China’s National People’s Congress. There are more peers than could ever sit in the chamber at the same time – and the bulk of the work of the House is done by a much smaller group of peers.

In the 2016/17 session 862 peers were officially members of the House of Lords, for some or all of the year.

During the session, 18 new peers joined, 11 died, 11 retired and 40 were ineligible to take part in the work of the House (leave of absences, membership of the judiciary, roles within the chamber and a suspension). On the first day of the 2016/17 session, the memberships of four peers ceased due to nonattendance during the previous session. This means a body of 779 peers served the entirety of the 2016/17 session and were eligible to vote in all 77 votes in the House; though as this report demonstrates, once again, not all did so.

The House of Lords is beginning to recognise this is a major problem. In October, the Lord Speaker’s Committee on the Size of the House published its report on how to reduce the numbers of peers. The report recommends moving to a 600 member house over the next 11 years. However, polling conducted for the ERS shows that this is still far too large (Polling conducted by BMG for the Electoral Reform Society, 16-17 October 2017, sample 1506 GB adults aged 18+. These results only include those who do not support abolition):

- 88 percent of people who oppose abolition believe the Lords should be under 600 members.

- 28 percent think the Lords should be between 400 and 500 members – far smaller than the Lord Speaker’s committee’s recommendations.

- The average size supported is 383 peers.

- Backing for a much smaller second chamber is consistent across all parties and demographics – 89 percent of Conservative voters and 93 percent of Labour voters want under 600 peers. As do 95 percent of UKIP voters and 91 percent of Liberal Democrat voters.

Most democracies have upper chambers which are around 100 members. India’s upper house is only 245 members, while France’s is made up of 348 members and Germany’s just 69.

Britain has no need – and voters have no desire – for a supersized upper chamber. The ERS has recommended a 300-seat upper house. Our research shows the majority of the work of the upper house is undertaken by around that number of peers. The top 300 voting peers account for over 64 percent of all votes in divisions during the 16/17 session.

A far smaller, dedicated revising chamber of full-time scrutineers would be both more accountable and more effective. In its consultation, the Lord Speaker’s committee ruled out any discussion of how peers arrive at the upper house in the first place. Yet, by far the most effective way of reducing the Lords’ size would be move to an elected house.

Support for an elected second chamber has grown over the past two years from 48 percent backing a partly- or fully-elected upper house in 2015, to 64 percent now (ibid). Twenty-seven percent of people think the second chamber should be abolished – up from 22 percent in 2015 – while only 10 percent think it should remain as it is.

On the issue of both size and composition, the House of Lords’ internal recommendations for reform are out of kilter with public opinion.

The cost of the Lords

Daily allowance and travel costs (We use ‘expenses’ throughout this report to denote just daily allowance and travel costs) for the 2016-17 session (We have omitted May 2016 expenses as the session did not start until the 18th May and the figures do not differentiate between sessions. As such this figure is likely to be a slight underestimation) came to over £19 million. Divided by the total number of peers for that session (862) this means the average peer received £22,273.69 – despite the house sitting for just 141 days. In 2016 (According to the ONS, the 2016 median gross weekly earnings for full-time employees was £539. Median annual gross income was therefore £28,028 and median take home pay £22.226) the median UK take home pay for full time adult employees was £22,226.25.

The 779 peers who served the entirety of the 2016/17 session and were eligible for all 77 votes in the House claimed expenses of £18,803,580, an average of £24,138.10 each.

If we remove the 102 peers that did not claim any expenses or were ineligible, the 677 remaining peers received an average of £27,774.86 each in tax free expenses.

In total, 455 peers claimed more than the average take home pay of full-time employees during the 2016/17 session.

Cost and contribution

Non-voting peers

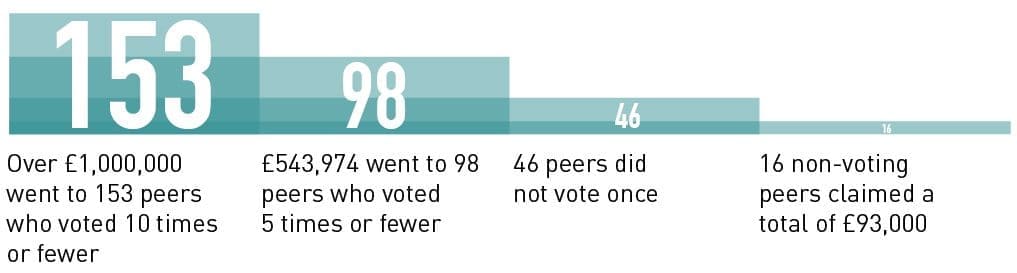

Of the 779 peers (This figure excludes those on leave of absence for the whole or part of the year, members of the judiciary and those prevented from voting because of their Parliamentary role.) eligible to vote for the whole session, 46 did not vote once. Of these, 16 claimed a total of over £93,000 in expenses. The majority of this sum was claimed by just a handful of peers.

Peers voting five times or fewer (98 peers or 13% of the total) claimed £543,974 in expenses, while peers voting ten times or fewer (153 peers) claimed over one million pounds.

Non-speaking peers

Of the peers eligible for the entirety of the 2016/17 session, 109 made no spoken contributions – with 63 of these claiming a total of £1,095,701 in expenses.

However, speaking in the chamber is one element of the broader work of the upper house. Following revelations that these ‘silent peers’ claimed over £1m last year, it was suggested that most of these peers make significant contributions in other ways. Our analysis shows that, unfortunately, that is not the case.

No committee membership

The ERS looked at committee membership of the silent peers. It shows that 87 of the 109 peers who failed to speak last year also failed to sit on any committees. These Lords claimed a total of £775,466.

This group of 87 voted on average just 18 percent of the time. Even those who claimed expenses, voted in just a quarter (26%) of votes on average. Moreover, 26 of the non-speaking, non-committee peers claimed over £10,000 each – despite voting on average just 37 percent of the time (16 claimed more than average UK take-home pay).

Non-questioning peers

Some of these peers however do submit written questions to government – an important tool for scrutiny. Yet of the 109 peers who have not made spoken contributions in the chamber, 91 also did not table any written questions in 2016/17.

When we look at these three primary scrutiny functions, there are 72 peers who have not spoken in the chamber, tabled a written question or served on a committee in the whole of 2016/17. This represents nearly one in ten peers. Thirty-three of these peers have claimed expenses. The 33 inactive peers:

- Claimed a total of £462,510 in 2016/17 – an average of £14,015.45 each

- Those claiming voted on average just a quarter of the time (24%). The majority of inactive claimants (21 of the 33) voted fewer than 20 times

- The 33 inactive, expenses-claiming peers voted a total of 620 times. That works out at £746 per vote

- 16 claimed over £10,000. And the top eight claimed more than UK average take-home pay. These peers claimed £269,213 between them.

Partisanship

It is often claimed that the House of Lords is more independent than the Commons and less driven by partisan politics. This is largely based on the fact that some Lords sit as Crossbench members who do not have a party affiliation. However, when we look at the actual activity in the upper house, the Lords takes on a very partisan appearance.

In this period, 601 out of 862 peers took a party whip (69.7%). And those who take a party whip also tend to be loyal to it.

Of the 251 Conservative peers who voted at least once, 197 (78%) never voted against the government and only 3 peers (1.19%) voted for the government less than 90% of the time. The average Conservative peer supported the government in 98.72% of the votes in the 2016/17 session.

Of the 200 Labour peers who voted at least once, 40 never voted for the government (20%) and 100 (50%) voted against the government more than 90 percent of the time. The average Labour peer voted against the government in 89.6 percent of votes in the 2016/17 session.

Crossbench members appear to vote less often. Out of 213 eligible, crossbench and non-affiliated peers, 87 (41%) voted fewer than 10 times in 2016/17 (72/183 Crossbenchers and 15/30 non-affiliated peers). This figure was only 14 percent for Labour (30/208), 7 percent for the Conservatives (19/259) and 6 percent for the Liberal Democrats (7/104).

Representation

The House of Lords continues to suffer a crisis of representation. Just 26 percent of peers are women, lower than any other political institution in the UK (32% of members of the House of Commons are women, 35% of members in the Scottish Parliament, 42% of members of National Assembly for Wales and 30% of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly). At the time of publication, Operation Black Vote lists just 46 peers as representing BME communities.

At the time of writing 141 peers are over 80 years of age, some 18 percent of the total membership, compared to just 6.6 percent of the over-21 population. 451 peers are over 70 (56% of the whole House), and 588 are over 65 (74% of the whole House).

Of the peers who did not contribute in the chamber during the 2016/17 session, 25 are over 80 (This includes Peers on leave of absence). Of the 100 peers who have voted the most often, 11 are aged over 80. This means that proposals such as introducing a mandatory retirement age would not significantly reduce strain on the House nor retain those who are hardest working.

Despite claims of career diversity, the largest employment background of peers by far is politics. Former MPs and representatives of other legislatures make up the bulk of appointees. As of April 2017, the House hosted 184 ex-MPs, 26 ex-MEPs, 11 ex-MSPs, 8 ex-Welsh AMs, 6 ex-London AMs, 11 ex-MLAs and 39 current or ex-council leaders.

Contrary to its repeated assertions, the unelected upper house does not have special claim to expertise, representation or independence. Britain’s undemocratic chamber has lost its last defence.

Conclusion

Time for reform

The second chamber is demonstrably in need of serious reform. Whether it is the thousands claimed by inactive peers or the dominance of defeated politicians, it is clear that until we let the light in, the rot within the Mother of all Parliaments will only get worse.

We must see parties commit to a far smaller, proportionally elected upper house. At a time of significant constitutional, economic and political change, the need for an effective House of Peers or Senate is overwhelming.

The ERS supports a fairly-elected upper house of 300 members. But whatever the final details, the principle remains: those who vote on our laws should be accountable to those affected by those laws. As we have shown, that is a matter both of principle and pragmatism.

Now is no time for minor tinkering; the public call for a real overhaul is loud and clear. Let’s get on with meeting our democratic duty – and give voters the revising chamber Britain needs.