Summary & Introduction

Summary

Politics at a local level is democracy at its most vivid – issues concerning education, transport and planning are discussed, debated and deliberated over by local people, elected mostly on a part-time basis, and with the best interests of their local communities at heart.

Policy formulation concerns which schools to keep open, and how often bins should be emptied. As a consequence, those who are interested in ‘quality of democracy’ or ‘social trust’ issues are often concurrently interested in the mechanics of local government – the two are often inseparable. The ongoing

debate about how to improve democracy and standards in public life has an excellent case study in Scottish local government.

It is clear that political parties have to embrace the new environment of coalition administration, and move away from the outdated language of who ‘won’ or ‘lost’ the election. Under STV, parties represent different proportions of the electorate, and have to try to work together for a greater good, as opposed to pursuing overtly partisan objectives on the false premise that they alone have the right to drive policy on the basis of 20-30% of the electorate that actually voted for them.

Electoral reform has led to parties used to holding power “sharpening their pencils”, as one senior council official puts it – either by virtue of leaving office or staying in power with a much reduced majority. There are numerous examples of staff, elected members and others ‘raising their game’ since May 2007 – even where there was not necessarily a dominant party in power for a long time. We see examples of local government policy-making being refreshed and becoming more strategic.

The scrutiny of policy-making in councils where one party has traditionally dominated disproportionately to its vote share has been improved as officers ensure the various opposition parties have more input to, for example, the budget setting process, as well the wider work of committees.

Parties are forced to work together through their individual members in the larger multimember wards – attempting to cover these new larger areas in the same way as pre- 2007 betrays the outdated territorial mindset of politicians who regard themselves as the sole representative of communities, despite often winning public office via a tiny proportion of votes.

Introduction

The introduction of the Single Transferable Vote (STV) to Scottish local government elections for the first time in May 2007 very clearly had the potential to change the face of council chambers across the country; electoral reform was implemented as part of an attempt to ‘renew local democracy’. As Professor Richard Kerley, chair of the committee that recommended the introduction of the Single Transferable Vote, stated at the time of his findings being released: “Democracy, by its very definition, is a matter that involves the whole population. We are concerned that a significant proportion of the population appears to take little part in the democratic process” (BBC News, 27 June 2000; see Kerley, Richard (2000) The Report of the Renewing Local Democracy Working Group (Edinburgh: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office).

The key premise of electoral reform in Scottish local government has been based primarily on the principle that better democracy leads to better governance. Three years on, this report seeks to discuss the various ways those involved in the process can fulfil their aims and objectives given the context of the new electoral system.

In doing so, there is a need to be clear about what this report is not:

First, its emphasis is not on whether it was the right decision to introduce STV to Scottish local government (although the ERS believes that it was) – rather, it is an analysis of how to make it work best now it has been introduced. While it is problematic to try and conclude whether or not the corporate business of local governance is ‘better’ than before, clearly, STV is the superior system if the aim is ‘quality of democracy’, as the Renewing Local Democracy working group has it. If the raison d’être of democracy is ‘rule by the people’, proportionality, multi-member wards and more councils under ‘no overall control’ achieve that objective more transparently. The concept of ‘consensus democracy’ involving as many actors as possible sharing power in coalitions is best achieved via this route. Nevertheless, that is not the main focus of this report.

Second, it should not be read as a didactic set of recommendations that parties must adopt at all costs – rather, it is a well-meaning collection of suggestions aimed at anybody interested in local democracy, especially those working in the Scottish policy community. Sometimes, it is understandably difficult for party activists to think in anything other than a ‘self-interested’ way – one of the problems with public debates about electoral reform is that they are mostly conducted by party politicians in a party political context. Nevertheless, it remains useful for them and others to contemplate the features of the ideal type of representative democracy, as that is hopefully to the benefit of all.

Third, this report is not the definitive analysis of Scottish local government after electoral reform. There are other researchers working on this topic, encompassing the fields of political science, public policy, public administration and management (For example, see Bennie, L. and Clark, A. (2008) ‘The Transformation of Local Politics? STV and the 2007 Scottish Local Government Elections’, Representation, 44, (3), pp225- 238; Bochel, H. and Denver, D. ‘A Quiet Revolution: TV and the Scottish Council Elections of 2007’, Scottish Affairs, No. 61, Autumn 2007. For a more historical perspective, see Midwinter, A. (1995) Local Government in Scotland (London: Macmillan), and McConnell, A. (2004) Scottish Local Government (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press). Linked to this, we must separate out external factors such as the impact of the large number of new councillors – just under 50 per cent – elected in May 2007, as well as some aspects of the changes to party representation in different local authorities, from that of the impact of the actual electoral system itself. It should also be added that this is an ongoing project and that, three years on, all findings should only be analysed within the context of recent change.

Certainly, the conclusions of the Renewing Local Democracy report provoke more universal questions which go far beyond the boundaries of Scottish local government. Why are voters apparently turned off modern party politics? What should a healthy ‘public sphere’ (and associated healthy ‘social capital’) actually resemble? The report utilises both survey and interview data to try to answer this key. Figures 1 and 2 below suggest that the basic way that parties interact with voters has been altered – and positively (There was a very close correlation between councillors who considered the introduction of STV to be a positive development, and whether they then thought the new system was working well. As a consequence, it is insightful to examine the relationship between this, and the other variable in question.) – since May 2007, but there is a need to unravel the detail of what that involves. In our survey of councillors, we found that a majority of councillors of all parties, including councillors of parties that opposed the introduction of STV, believe that STV has changed the way parties interact with the public:

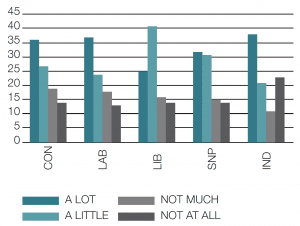

Figure 1. Has interacting with the public been affected (by party)? (%)

While it is perhaps unsurprising that most councillors who favoured the introduction of STV believe it has changed the way parties interact with the public, we found that even amongst those who opposed STV there is a majority who think it has made a difference.

Figure 2. Has interacting with the public been affected (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

It is hoped that this report will go some way towards providing examples of good practice under the new system. A key criticism of majoritarian systems is that it makes campaigning in safe seats a futile exercise for all parties. A first-past-the post system encourages parties to mimic one another, and appeal to the swing voter, rather than to the majority of voters, where turnout is often low. A more proportional electoral system abolishes these safe seats, transforming them potentially into places for all parties to campaign, and in the process pay more attention to the local issues which affect them.

However, an electoral system cannot be changed effectively without the compliance of the key actors – the parties and their politicians – so it is vital that they fully embrace the reforms that have been introduced, part of the wider remit to improve and renew local government in post-devolution Scotland.

Forming Coalitions

The merits of consensus

The full extent of the impact of the introduction of STV to Scottish local government is continuing to emerge. However, it is already possible to examine aspects of the substantial challenges which STV’s introduction posed for party machines, and whether or not they were successfully met. The level of detail acquired here is informative in terms of building our knowledge of how parties operate in modern politics, especially when we bear in mind the wider debates concerning the ‘professionalisation’ of parties, and their apparent disconnect from voters. The four main parties in Scotland currently have a combined membership of around 50,000 people (Based on the parties’ own interpretation of their membership: Labour – 18,500, SNP – 15,000, Conservatives – 15,000, Liberal Democrats – 4,000.) – only one per cent of the population – and local politics, in particular, is an area where the link between elected representatives and citizens is especially important.

The Renewing Local Democracy Report (2000) argued clearly that there exists a very direct link between democracy and good governance – and that the latter flows from the former. Perhaps more than any other level of government, local politics requires that local political decision-making is in tune with local people. Council leaders live and work in the same community – the link between how members are elected and what they then try to do in office is very real. More specifically, within the context of May 2007 (See Baston, L. (2007) Local Authority elections in Scotland (London: Electoral Reform Society) for a full analysis of the results), while civic engagement via campaigning in elections is important, so too is the efficacy of the way parties form the governing administrations after the elections are over. Coalitions between parties in local government are natural and established so the fact that parties like Conservative and Labour, or SNP and Liberal Democrat, have gone into partnership with one another in a way that would not be possible in the Scottish Parliament, should not be viewed as a surprise. Indeed, councillors and officials often let this phenomenon pass without comment.

Coalition government – along with minority government – is not an unfortunate by-product of proportional representation, it is one of its most important features. If a party has not succeeded in winning anywhere near to 50 per cent of the vote in a constituency or local authority area, should it always be entitled to govern with 100 per cent of the seats around the executive table? Indeed, this does not even take into account the percentage of the electorate which actually voted, an ever diminishing number if one examines Westminster General Election contests since 1950, for example. Democracy means ‘rule by the people’ and it is hugely important that modern democracies represent that aspiration as accurately as possible.

In fact, local authorities in Scotland have been attuned to coalition government for some time. Even before 2007, 11 councils were run by either a coalition or a minority administration. Further, it could also be argued – if one wishes to be especially sceptical – that local politics, with its focus on (relatively) ideologically-free issues such as waste disposal and transport, is much better suited to consensus than other levels, for example, Westminster. Regardless, with the significant increase in coalitions and/ or minority administrations across 27 of the 32 Scottish local authorities, it is clear that parties have to embrace this new environment, and not continue to pursue overtly partisan objectives that are more suited to the old majoritarian system.

Figure 3. Was administration formation affected (by party)? (%)

There is a clear and real link between the way councillors are elected, and the way they go on and form an administration, so the above graph is quite sensible. Even if a council is ‘normally’ run by a coalition administration (pre-2007), the coalition now in charge will certainly be generally different from before. The slightly lower figure for the Independent councillors can be explained by their concentration in rural councils like Highland and the island administrations where it is, to an extent, ‘business as usual’ from this perspective.

Figure 4. Was administration formation affected (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

The detailed breakdown tells us that slightly more respondents who were in favour of electoral reform feel that the way ruling council executives were formed had changed ‘a lot’. The most immediate change after the first STV elections was the larger variety of coalitions than had previously existed under First-Past the Post:

Table 1. Control of local authorities 1995-2007

|

1995 |

1999 |

2003 FPTP |

2003 STV* |

2007 STV |

| Aberdeen |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Aberdeenshire |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Angus |

SNP |

SNP |

SNP |

NOC |

NOC |

| Argyll and Bute |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

NOC |

| Clackmannanshire |

Lab |

NOC |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| Dumfries and Galloway |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Dundee |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| East Ayrshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

| East Dunbartonshire |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| East Lothian |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| East Renfrewshire |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Edinburgh |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| Falkirk |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Fife |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Glasgow |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

| Highland |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

NOC |

| Inverclyde |

Lab |

NOC |

LD |

LD |

NOC |

| Midlothian |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

| Moray |

SNP |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

NOC |

| North Ayrshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

| North Lanarkshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

| Orkney |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

| Perth and Kinross |

SNP |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Renfrewshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| Scottish Borders |

Ind |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| Shetland |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

| South Ayrshire |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

NOC |

| South Lanarkshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

| Stirling |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| West Dunbartonshire |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

| West Lothian |

Lab |

Lab |

Lab |

NOC |

NOC |

| Western Isles |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

Ind |

|

1995 |

1999 |

2003 FPTP |

2003 STV* |

2007 STV |

| Labour |

20 |

15 |

13 |

7 |

2 |

| Lib Dem |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| SNP |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Independent |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

| NOC |

3 |

10 |

11 |

18 |

27 |

* Based on a pre-election ERS modelling exercise of how seats would have been allocated.

Table 2. Party coalitions post-2007 elections

|

Con |

Lab |

LD |

SNP |

Ind / Oth |

| Aberdeen |

X |

X |

Leader |

Partner |

X |

| Aberdeenshire |

Partner |

– |

Leader |

X |

X |

| Angus |

Partner |

Partner |

Partner |

X |

Leader |

| Argyll and Bute |

X |

– |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

| Clackmannanshire |

X |

Minority |

X |

X |

X |

| Dumfries and Galloway |

Leader |

X |

Partner |

X |

X |

| Dundee* |

Support |

Leader |

Partner |

X |

X |

| East Ayrshire |

SupportX |

– |

Minority |

Support |

|

| East Dunbartonshire |

Partner |

Leader |

X |

X |

X |

| East Lothian |

X |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

X |

| East Renfrewshire |

X |

Leader |

Partner |

Partner |

Partner |

| Edinburgh |

Support |

X |

Leader |

Partner |

X |

| Falkirk |

Support |

Leader |

– |

X |

Partner |

| Fife |

X |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

X |

| Glasgow |

X |

Control |

X |

X |

X |

| Highland** |

– |

X |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

| Inverclyde |

X |

Minority |

X |

X |

X |

| Midlothian*** |

– |

Minority |

X |

X |

– |

| Moray |

Partner |

X |

– |

X |

Leader |

| North Ayrshire |

X |

Minority |

X |

X |

X |

| North Lanarkshire |

X |

Control |

X |

X |

X |

| Orkney |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Control |

| Perth and Kinross |

X |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

– |

| Renfrewshire |

X |

X |

Partner |

Leader |

– |

| Scottish Borders |

Partner |

– |

Partner |

X |

Leader |

| Shetland |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Control |

| South Ayrshire |

Minority |

X |

– |

X |

X |

| South Lanarkshire |

Partner |

Leader |

X |

X |

X |

| Stirling**** |

X |

Leader |

Partner |

X |

– |

| West Dunbartonshire |

– |

X |

– |

Leader |

Support |

| West Lothian |

Support |

X |

– |

Leader |

Partner |

| Western Isles |

– |

X |

– |

X |

Control |

*March 2009 – SNP/Independent administration takes over **August 2008 – Independent/ Liberal Democrat/ Labour administration takes over

***June 2008 – became majority administration

****March 2008 – SNP minority administration takes over

|

Con |

Lab |

LD |

SNP |

Ind / Oth |

| Control |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| Minority administration |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Single party rule |

1 |

6 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

| Coalition Leader |

1 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

| Leading council |

2 |

12 |

3 |

7 |

8 |

| Junior Partner |

6 |

1 |

10 |

5 |

3 |

| Part of administration |

8 |

13 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

| EXternal support |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| Opposition |

13 |

14 |

10 |

18 |

15 |

| Not on council |

6 |

5 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

However, there is evidence of some local parties either choosing to form a minority executive, having been unable to form an effective coalition, or ending up in opposition for similar reasons. Further, there are examples of parties forming large coalitions which appear to be united only by their dislike of one of the other parties. It would be wrong to criticise specific local parties for this, as such outcomes are often an unavoidable practicality. Nevertheless, it is interesting to highlight cases that perhaps appear to reflect individual councillors in some local parties failing to think constructively, and acting overly ‘competitively’.

In Angus, the ruling Scottish National Party (SNP) won significantly more seats than the other parties, who appear to have formed an expedient anti-SNP coalition. In East Dunbartonshire, the Conservatives and Labour joined forces to overcome the Nationalists, although a lack of first preference votes and inexperience on the part of the latter may both also have played a part here. A similar fate befell Labour in West Dunbartonshire and West Lothian where, despite being the largest party, they now sit in opposition. In Dundee City, there was an attempt by Labour to hold on to power via a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, despite the SNP getting more seats, and this has since collapsed following by-election results. In Fife and Renfrewshire, the SNP took power via coalitions, despite not winning more seats than Labour.

Meanwhile, Clackmannanshire, Midlothian and North Ayrshire saw Labour continue in power as a minority party, despite opportunities for other parties to form coalitions, and they also now run Inverclyde as a minority. In Stirling, there developed a similar situation to Dundee City, with a change in coalition since May 2007 after Labour tried to remain in office with the Liberal Democrats. But now the SNP run it as a minority following a vote of no-confidence (although Labour had still been the largest party in 2007). In Highland, the Independent-SNP coalition has failed to survive, and the Independents now run the council along with Labour and the Liberal Democrats, while the Conservatives in South Ayrshire also opt to govern alone.

The above cases do not necessarily represent ‘bad practice’ – indeed, in many of them, there is an element of new parties entering local government executives and significantly refreshing the political landscape. In particular, the Conservative Party deserves credit in the five local authority areas where it offers support to the ruling executive, regardless of which party is in power – in fact, evidence from ERS research interviews suggests that the party would be serving in many more administrations if the SNP had not imposed a ban on their councillors working with them – a partisan policy which has now thankfully been abolished.

Case Study 1: Fife

Fife

The coalition administration which has operated in Fife since May 2007 is an example of how two different political parties can come together quite naturally in local government, despite ideological disagreements at a national level, as well as the fact that they represent quite distinct types of wards within the local authority. Furthermore, it is an example of a new partnership coming into power after electoral reform, replacing the same one party holding control for some considerable time. Finally it is an example of a coalition relatively accurately reflecting transfer patterns and overall proportionality. The SNP received 27.8 per cent of first preference votes (and 23 seats), the Liberal Democrats 22.4 per cent (and 21 seats), with Labour receiving 28.7 per cent (and 24 seats).

The SNP has representation in most wards, with particular strength in the new town of Glenrothes. Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats dominate the East Neuk of Fife, centering on the historic university town of St. Andrews.Despite this cultural disconnect, the two parties were able to form a coalition partnership in May 2007 and it remains strongly intact and working well in 2009 when this report was written.

A Fife housing association member interviewed considered the coalition had been quite successful in papering over party differences in housing-related issues e.g. a Liberal Democrat dominated local area committee opposed a housing association bid to build in part of North East Fife, despite the obvious electoral implications that the decision entailed. The coalition has also not shied away from taking difficult judgements regarding school and post office closures, and other public sector cuts. There is a significant difference between implementing policies simply because they are popular electorally and taking more difficult decisions and the SNP/Liberal Democrat coalition running Fife Council has shown it is prepared to strongly push through plans that they think are correct. Coalition government then, while more representative of voter preferences, does not necessarily result in a lack of policy direction and/or a weakness of leadership.

Planning Policy

Greater selflessness without sacrificing self-interest

In the United States, party labels are weak affiliations which can be adapted to the local candidate and area where the election contest is being conducted. A career in Washington politics is almost always preceded by a career in the state legislature first. A similar situation exists in Germany where national politicians find their feet in regional politics. In France, politicians are educated in public administration at the national ‘grandes écoles’ before going on to serve in government in Paris. In the UK, however, it is the party that offers the ambitious young aspiring politician the only route to power, and that restriction permeates all levels of government, including local authorities. The consequence, of course, is that it is to the party that these politicians owe their first loyalty, ahead of the voters, and ahead of any one policy. That is not to say that politicians in Britain do not generally mean well or that their ‘self interest’ might not have very positive consequences for the country as a whole. In particular, the conviction politician with total faith in the ‘superiority’ of his or her party is, in many ways, an honourable individual who should not be belittled. Nevertheless, it is clear that voters do not like politicians appearing to put their parties first and / or parties appearing to stick together as an elite or ‘cartel’.

Public policy-making in a democracy is rightly fuelled by electoral motivations i.e. ‘our voters want us to do this so we will do it’. However, it does not automatically follow that public policy should fail to take into account other considerations e.g. the ability of the administration to pay for the policy in the first place. Or the ability of an opposition party to also come up with a ‘good idea’, and for there to be co-operation between different parties without too much concern about how it will ‘play at the polls’. Linked to this, one of the advantages of the Single Transferable Vote is that ‘safe seats’ (or ‘jobs for life’ for the politician lucky enough to hold one) are abolished, along with ‘one party states’ i.e. local authorities where one party holds power both individually and continually for an extremely long time. The corollary of both those phenomena is that policy-making both ceases to be responsive to voters – because the politicians know that they will win the next election anyway – and also starts to focus inwardly on its own machinery.

Electoral reform has led to parties used to holding power “sharpening their pencils”, as one senior council official put it in an interview – either by virtue of leaving office or staying in power, but with a much reduced majority. Speaking to senior officers in East Dunbartonshire and Edinburgh City, there are numerous examples of all staff, elected members and others ‘raising their game’ – so even where there was not necessarily a dominant party in power for a long time, we see examples of local government being ‘refreshed’. One of the reasons the Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (the SCVO – an organisation representing significantly more members than any of the political parties) supported the introduction of STV was that it would open up decision-making for a greater number of interests.

Case Study II - Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire

The local authority of Renfrewshire (pop. 170, 000) centres upon the largest town in Scotland – Paisley – and forms part of the Greater Glasgow conurbation. Prior to May 2007, the council had been run by the Labour Party since its single tier inception in 1995. It is now run by a SNP (17 seats) / Liberal Democrat (4 seats) coalition.

While the coalition may appear similar to that of Fife, the dynamic in Renfrewshire is significantly different. First, the SNP has considerably more seats than the Liberal Democrats, who are very much the junior partners in the coalition. Second, the Paisley Labour Party had been at the centre of a series of scandals and examples of internal corruption, particularly acute in the late 1990s, which may have led towards a gradual rise in support for the SNP and a gradual decline in support for Labour. While it would be too simplistic to argue that the communities of Renfrewshire had experienced a similar gradual decline in attention as a result of this, it is nevertheless reasonable to point to examples where bridging social capital (Inter-personal networks, democratic participation or civic engagement) has been weakened due to a local council out of touch with the interest of ordinary voters and looking inwards to its own problems, safe in the knowledge that it is has an ongoing majority of first-past-the-post seats.

This means that any new administration has the opportunity, not just to offer an alternative to the old Labour-run Renfrewshire, but actually to offer an entirely new type of politics. Parallels can be drawn here with the national level – those who argue that a proportional electoral system spreads power more effectively around the country, rather than concentrating it in ‘safe seats’, could equally point to councils like Renfrewshire, pre-2007, where power was concentrated in some parts of the local authority area, at the expense of others. Its new administration receives plaudits from a number of different sources, including opposition councillors, one of whom mentioned in an interview that the re-birth of Paisley “is clear for all to see”. It is obvious that this is not simply due to a new set of faces in the council chamber. The SNP group compiled a manifesto prior to being elected, as well as producing both a strategic council and community plan for Renfrewshire once they had formed the new coalition administration with the Liberal Democrats.

While it is a subjective question as to whether or not the policies that the council have pursued over the last two years have been the right ones, it is clear that electoral reform has refreshed local government in Renfrewshire.

Scrutinising decision-making

Providing constructive opposition

Effective scrutiny of the new council administrations across Scotland is vital, and should be able to be facilitated much more easily by the new system. Ultimately, a closer representation of votes in seats means a greater number of opposition councillors, whose primary role is to scrutinise the policies of the governing administration. But is this actually happening?

Figure 5. Have debates been affected (by party)? (%)

The pattern here is not clear at all across the parties. For Labour, Liberal Democrat and Independent councillors, there is a view that chamber debates have been affected either ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’.

However, Scottish Nationalists, in particular, appear much less convinced – this may be related to the fact that many of them are new and have little with which to compare.

Figure 6. Have debates been affected (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

Those who were not in favour of the introduction of STV are more consistent in their view that debates have been affected in a certain way – although a significant majority do think that debates have changed; for those who were in favour, there is a lack of consensus over its impact, with most opting for ‘a little’, so the overall pattern here is not clear.

A short term rise in partisanship8 between SNP and Labour members has occurred in councils where the former has taken over from the latter. Labour members regard SNP members as being ‘naïve and inexperienced’ while SNP members regard Labour members as being ‘sore losers’. This is not a problem for the system itself, however, and merely reflects contemporary national political patterns. Indeed, there are actually significant elements of a zero sum game throughout this survey e.g. one councillor’s ‘better scrutiny’ is another’s ‘rise in partisanship’; one councillor’s enthusiasm for being able to get elected on a second preference is another’s disdain at those who have to. An Independent councillor in Highland seems duty bound to bemoan the rise of partisan representation in a way that a newly elected SNP councillor in that localauthority is equally duty bound to enthuse about the opening up of competitive elections in the region for the first time. However, there is no need for reinforced oppositions to oppose everything – it is possible to scrutinise but constructively. Politics does not necessarily have to equal conflict or division, particularly at a local level.

The scrutiny of policy-making in councils where one party has traditionally dominated disproportionately to its vote share has been improved as officers ensure the various opposition parties have more input to, for example, the budget setting process. A Conservative councillor, not in favour of electoral reform, nevertheless stated in a focus group: “You have to make sure you read everything now”. An Angus councillor also spoke very positively on this aspect – while not in favour of multi-member wards he accepted the logic of proportionality with regard to policy-making. Another Conservative councillor stated: “I preferred one member wards but overall, proportionality of representation makes for a better decision-making/business management model”. A new council leader: “Scrutiny is better, officers have to negotiate – we need to sell everything”. A Midlothian councillor: “There are actually debates in the chamber now”. An executive director of service pointed to the dramatic rise in the number of questions asked in council chambers across Scotland since May 2007 – clear evidence of a beefed-up scrutiny process.

Case Study III - Glasgow City

Glasgow

If there was one local authority that epitomised the inaccurate representative nature of a first-past-the-post electoral system, it was Glasgow City Council. In 2003, the Labour Party won 90 per cent of seats on the basis of 48% of the popular vote (and on the basis of a 40% turnout overall). As a consequence, debates in the council chamber were often ‘one-sided’, with the number of backbench councillors’ participation levels rather limited, to say the least.

However, in 2009, Glasgow “has a council again”, as one senior officer put it. Council staff now compile briefings for all the sizeable opposition councillors (34), with even the five Greens able to put together an alternative budget in 2007. The 22 SNP councillors – one in each ward, with two in Baillieston – have asked a significant number of questions since May 2007, and are attempting to hold the executive to account in a way that simply was not possible prior to May 2007. If the Renfrewshire case study highlighted the importance of public policy-making not becoming the victim of internal party politics, the Glasgow City case study shows how a greater number of opposition councillors can play just as pivotal a part in that process. There have been examples, sadly, of new councillors unable to oppose without resorting to negative tactics – nevertheless, the fact they exist in the numbers that they do is surely good for democracy in its widest sense. Meanwhile, committees are beefed up with non-Labour party members.

These are small but important steps towards a Glasgow that reflects the views of the voters who turned out in May 2007 – the 8 per cent who are Conservatives, the 8 per cent who are Liberal Democrats, the 25 per cent who are Scottish Nationalists and the 7 per cent who are Greens.

Along with Midlothian and North Lanarkshire, Glasgow remains a true Labour stronghold, where it commands a majority administration. However, no party should regard that position as some sort of ‘birth-right’, and there is evidence that a new type of politics is now emerging in Scotland’s largest city.

Operating in multimember wards

Being less territorial

Scottish local government has had multimember wards before (and under a majoritarian voting system too) while prior to reorganisation in 1995, everyone had two councillors – a district and regional one, an essentially hierarchical structure.

Figure 7. Have multi-member wards affected party interaction (by party)? (%)

A real consensus exists that the introduction of multi-member wards has had an impact upon the way parties interact with each other.

Figure 8. Have multi-member wards affected party interaction (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

Figure 9. Have multi-member wards affected internal party politics (by party)? (%)

Labour respondents appear to be especially convinced of the impact here – for obvious reasons related to the party having the most cases of multi-member representation – and there is the interesting related question of whether or not parties now have much less control over their elected members. For example, if three members get on very effectively in a ward, do they start to develop a ‘ward loyalty’? Two to three years in to the first new session of local government under STV, it is perhaps a rather mixed picture with anecdotal but not universal evidence of the above.

Figure 10. Have multi-member wards affected internal party politics (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

Figure 11. Have multi-member wards affected interaction with the public (by party)? (%)

Figure 12. Have multi-member wards affected interaction with the public (by councillors’ views on STV)? (%)

There appears to be one key aspect when

analysing the impact of multi-member wards – the relationship between ward size and collegiate working practices. While ward size forces councillors to refocus their work patterns, some clearly feel that they must replicate their pre-2007 activities on a larger scale – yet such a mentality betrays an individualistic approach to being a councillor which STV aims to curtail. Parties are forced to work together through their individual members in wards – whether they like it or not.

A Western Isles councillor stated: “you have to share more”. The traditional link between a single councillor and his/her electors has been altered but there is no need for concern over the problem of councillors in wards ‘free-riding’ i.e. not pulling their weight but taking the credit for other’s achievements (see page 25). As one Conservative councillor put it in an interview, multi-member wards are ‘management issues’ – if there is a problem with them, it can be solved i.e. if you want to make them work, they can work. There is little evidence of councillors coming into conflict with one another on a huge scale and/or not working together – members are very keen to be seen to be collegiate. There is also little evidence that work is being duplicated or officers are not coping with having three or four councillors in each ward perfectly effectively. Finally, there is no statistical evidence that a councillor’s age or experience necessarily affects their opinion of multi-member wards.

Case Study IV: Rural Local authorities

Rural Local authorities

The evidence from the survey suggests that the biggest challenge for an individual elected member is the introduction of the new multimember wards – few take issue with the premise of proportionality but many have a problem with not having their own ward. These new wards cover larger areas and involve the three or four councillors working together to serve their constituents. However, for a variety of reasons all centering around the ‘territorial mindset’ of the experienced councillor, large numbers have expressed concerns about the logistics of the new wards.

These concerns are particularly acute in rural areas where ward size is often vast, and where wards are held by Independent councillors who are ‘independent’ for a reason i.e. they do not regard any of the four or five main parties in Scotland as sufficiently able to represent their views – so they go it alone, and adopt a pragmatic approach to individual policies. Many of these councillors have served their wards for some considerable time, and naturally, are not particularly enthusiastic about sharing their area with other members. An ERS focus group revealed the deep anger that some feel that they and their colleagues were now having to stand for election and/or collaborate in their wards with other elected members.

None of the above is to argue that the Independent tradition of council representation across the Highlands of Scotland is without its merits. However, the practice of wards being held for decades unopposed by the same councillor who proceeds to monopolise representation amongst their local communities, was an aspect that required attention every bit as much as the old one-party states of Glasgow City, Midlothian or Angus.

The introduction of ward forums in Highland Council is to be applauded, especially the explicit aspiration mentioned in related official Highland Council documents that they should try to cement local networks and promote bridging social capital. The size of wards in Highland in relation to the number of councillors is far from ideal but that does not mean that Independent councillors used to having their own ‘patch’ should seek to continue to operate as they have always done. Democracy in rural parts of Scotland was in need of renewal every bit as much as in the urban central belt, and it is vital that long-serving councillors do not adopt spoiling tactics out of self-interest. If you are of the view that your new ward is too big for you to operate, why not consider collaborating with another councillor as part of a team? It is just possible that ‘your’ constituency [sic] might appreciate it.

The new wards have a much wider cross-section of society’s challenges within them, and require members to pool their resources and training to tackle them. On the whole, voters are not interested which councillor or party solves any problem that they might have had so long as the issue is solved – the sacred ‘councillor-voter’ link is significantly higher up the former’s list of priorities than it is the latter’s.

Looking to the future

The future

Being a councillor should be about giving something back to your local community via public service – it should not be about holding a ward for life on the off-chance a safe Westminster seat for your party then comes up in the area. Local politics ought to be less partisan (in the true sense of that term) and also less linked to national trends. In 1976, Professor Kenneth Newton argued that local elections had merely become “a sort of annual General Election” (Newton, K (1976) Second City Politics (London: OUP)). In 1995, Professor Arthur Midwinter wrote that this trend was really “contrary to the norms of British representative government, where the notion that the election to public office is a prerequisite of effective and responsive government” (Midwinter, A (1995) Local Government in Scotland (London: Macmillan)). If local elections had become simply a referendum on the performance of the Westminster government, something had clearly gone wrong, and required attention.

However, a better quality of democracy often means more ‘politics’ (for example, fewer safe seats and fewer one party administrations) so it is important that parties play their part constructively. It is worth reiterating that the new electoral system is not designed for the convenience of politicians – the fundamental premise of any system is to convert the preferences of voters into as accurate a representation as possible, with the business of government subsequently flowing from that. STV is not designed to make the life of a politician easier – it is designed to represent the choices of voters as effectively as possible.

For example, it has been tacitly argued that a sure way of making multi-member wards work better is for politicians to work more closely together and share out duties as they deem appropriate. However, in many ways, it is up to the politician to best calculate if this is the correct strategy – he or she has many options.

That is the essence of democracy. The ongoing debate about how to improve democracy and standards in public life has an excellent case study in Scottish local government. Politics at a local level is democracy at its most pure. If the process breaks down due to tribal party politics, local voters rightly voice their annoyance that their councillors have lost sight of their wider responsibilities, and it is that basic dynamic which lies at the heart of all democratic politics – the voter ultimately possesses the most power, and any authority held by an elected representative is accompanied by both accountability and responsibility.

Appendix

Methodology

Project timeframe: February to May 2008

First surveys sent out: 25th February

Reminder surveys sent out: 25th March

Preliminary findings completed and disseminated: 12th June

Survey

Total n = 454 (out of 1222)

This represents 37% of all councillors in Scotland elected in May 2007.

Detailed party breakdown

Conservatives 59

Labour 97

Liberal Democrat 81

SNP 137

Independents 66

Other 14

Interviews

70 conducted from March ‘08 to March ‘09:

Politicians

Focus groups for parties (4 panels involving 21 councillors)*

Follow-up telephone interviews with councillors (30) – including 10 council leaders in total

Officers

Face-to-face interviews with senior officers at council headquarters (5 visits involving 12 officers)

Telephone interviews with chief executives (7)

Detailed local authority survey response breakdown

|

Freq |

Percent |

| Aberdeen City |

19 |

4.2 |

| Aberdeenshire |

28 |

6.2 |

| Angus |

12 |

2.6 |

| Argyll & Bute |

17 |

3.7 |

| Edinburgh |

21 |

4.6 |

| Dumfries & Galloway |

8 |

1.8 |

| Clackmannanshire |

3 |

0.7 |

| Dundee |

9 |

2 |

| East Ayrshire |

15 |

3.3 |

| East Dunbartonshire |

7 |

1.5 |

| East Lothian |

11 |

2.4 |

| East Renfrewshire |

10 |

2.2 |

| Falkirk |

7 |

1.5 |

| Fife |

30 |

6.6 |

| Glasgow |

28 |

6.2 |

| Highland |

31 |

6.8 |

| Inverclyde |

12 |

2.6 |

| Midlothian |

4 |

0.9 |

| Moray |

173.7 |

|

| North Ayrshire |

11 |

2.4 |

| North Lanarkshire |

17 |

3.7 |

| Orkney |

9 |

2 |

| Perth & Kinross |

17 |

3.7 |

| Renfrewshire |

11 |

2.4 |

| Scottish Borders |

15 |

3.3 |

| Shetland |

2 |

0.4 |

| South Ayrshire |

16 |

3.5 |

| South Lanarkshire |

27 |

5.9 |

| Stirling |

7 |

1.5 |

| West Dunbartonshire |

5 |

1.1 |

| West Lothian |

10 |

2.2 |

| Western Isles |

14 |

3.1 |

| Missing |

4 |

0.9 |

| Total |

454 |

100 |